When Infants in Incubators Were a Sideshow Attraction

Archival photographs show the spectacle of babies who went on display, in an effort to save their lives.

Before Lucille Horn came to be under the care of Martin Couney, in 1920, the doctors who’d brought her into the world had provided a bleak prognosis. “They didn’t have any help for me at all. It was just: you die because you didn’t belong in the world,” she later recalled. Horn had been born prematurely, weighing around two pounds; her twin had died at birth. Hospitals at that time did not treat such small babies, but her father knew someone who did. So he bundled her up and took her to the only place he knew that might be able to care for her: a sideshow attraction at New York City’s Coney Island, which featured babies in incubators.

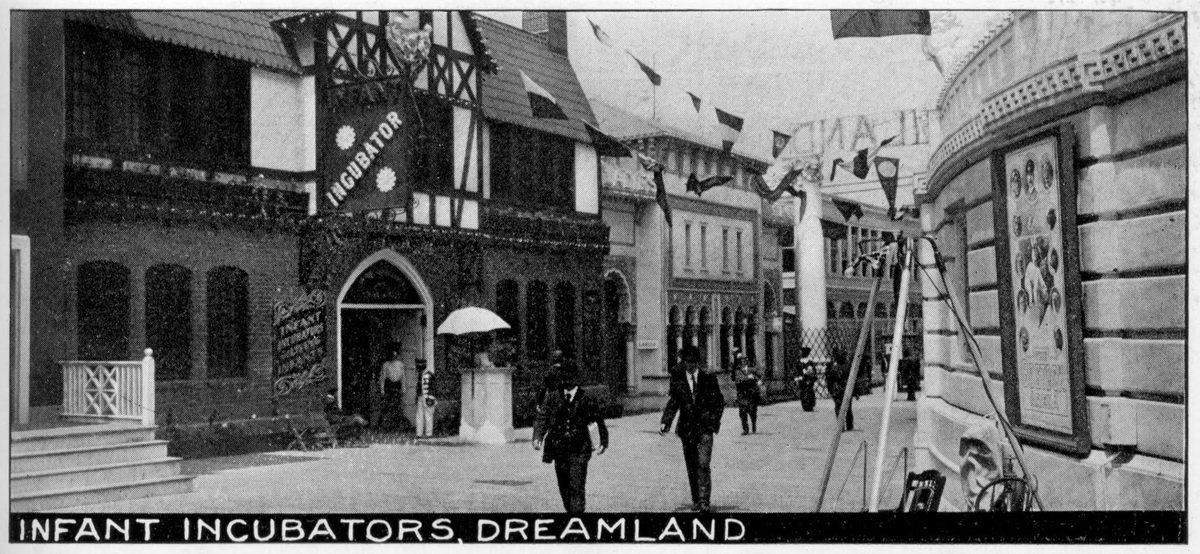

Incubators were still relatively new by the time Couney set up at Coney Island. Developed for infants in the 1880s, in Paris, Couney first displayed incubators—with babies—at the Berlin Exposition in 1896. From there he traveled to more expositions, including an event in London in 1897 and the Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo in 1901. But in 1903 he settled in the U.S. to run his babies-in-incubators summertime sideshow, which would continue until the early 1940s.

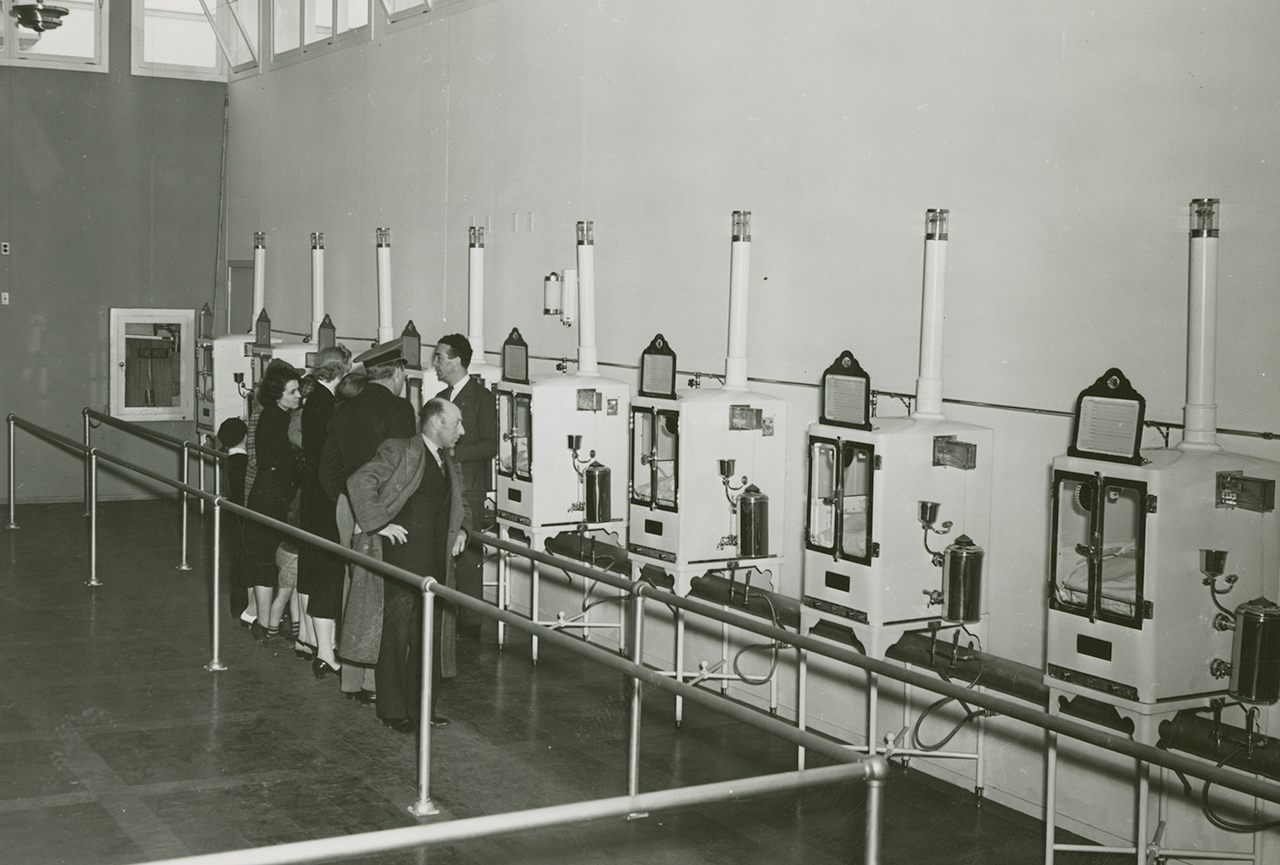

The premise of the attraction was straightforward enough: pay an entrance fee to see something you wouldn’t usually be able to see. What set Couney’s sideshow apart was that his subjects were premature babies in incubators, receiving care that hospitals did not provide. The entrance fees he collected went toward his operating costs, including round-the-clock care and wet nurses. Couney did not charge the parents of his tiny patients.

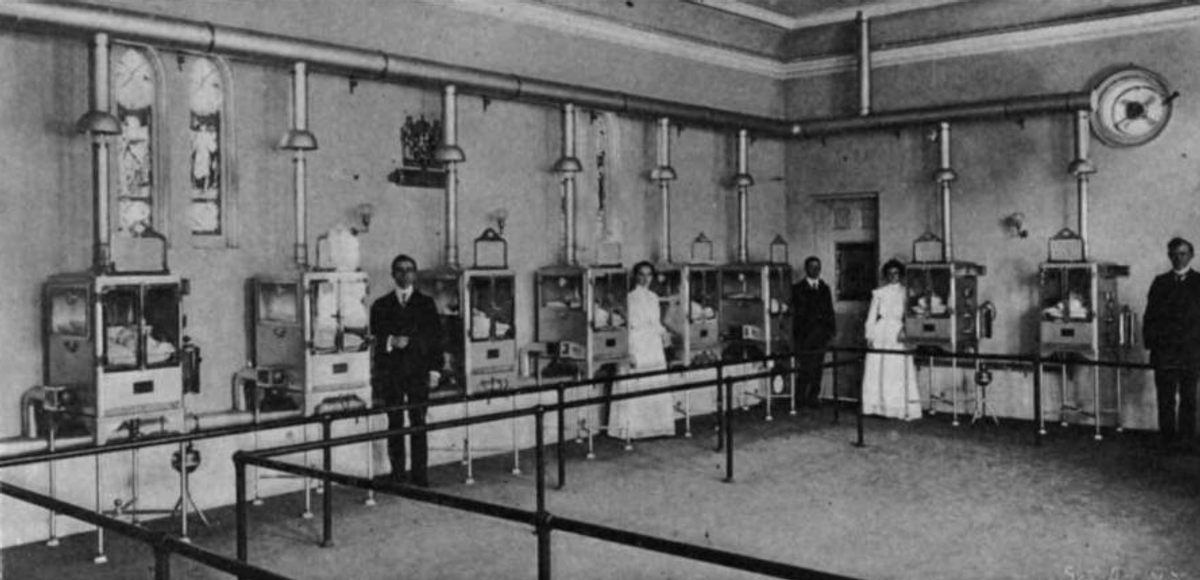

Reporting in 1903, The Brooklyn Daily Eagle described the “seriousness and value of the system shown.” A visit to Couney’s showcase revealed rows of warmed, glass-fronted incubators supplied with filtered air, containing “little pitiful pinched looking waifs… the only things that indicate that they are alive are the healthy color of their little faces and the faint flutterings of movement which are perceptible on closer inspection.”

In the new book The Strange Case of Dr. Couney: How a Mysterious European Showman Saved Thousands of American Babies by Dawn Raffel, recently reviewed by JSTOR Daily, Raffel reports that Couney may not have actually been a doctor. He also seems to have been cognizant of the theater element of a good sideshow. On occasion, he reportedly dressed infants, as they grew, in too-large clothing; his nurses were known to have slipped a finger ring around the entire wrist of their tiny charges. Speaking to the New Yorker in 1939, Couney explained, “all my life I have been making propaganda for the proper care of preemies, who in other times were allowed to die,” he said. “Everything I do is strict[ly] ethical.”

By one estimate, Couney saved the lives of 6,500 infants. His decades of caring for premature babies has been credited in the development of neonatal care in hospitals. But by the early 1940s, interest in Couney’s exhibition had waned and hospitals were beginning to open units dedicated to the care of premature babies. Couney died in 1950, at age 80. At the time of his death he was reportedly broke, but he was memorialized in The New York Times as “the incubator doctor.”

In 2015, two years before she died at the age of 96, Horn was asked by her daughter, as part of NPR’s StoryCorps program, about being on display as a tiny infant. “It’s strange,” she said, “but as long as they saw me and I was alive, it was all right.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook