Student Life at the First Medical College for Women

The pioneering women who faced jeers and discrimination to become doctors.

In early November 1869, Anna Broomall, a student at the Woman’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMCP), received a note. It had made the rounds among her male counterparts at the University of Pennsylvania Medical School before a clinical lecture at Pennsylvania Hospital. For the first time, WMCP students were to attend this lecture, which was an essential, hands-on experience for medical students. The message on the slip of paper was significant enough that Broomall kept it for more than 50 years: “Go tomorrow to the hospital to see the She Doctors!”

On Saturday, November 6, Broomall recalled, she arrived at the lecture along with 19 other young women. What happened next became known as the “Jeering Incident.”

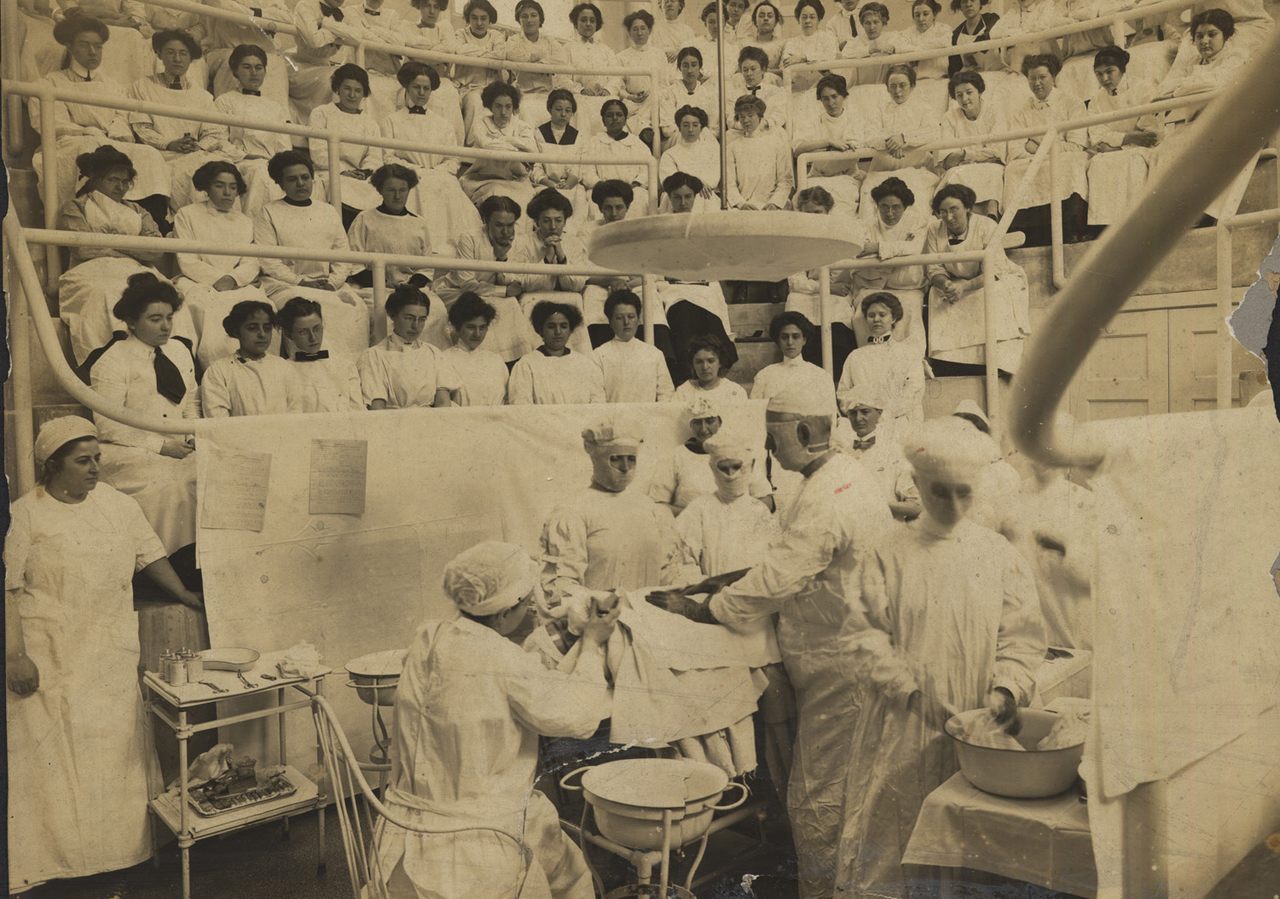

“When we turned up at the clinic, in what was then the new amphitheater, pandemonium broke loose,” Broomall said in a later interview. “The students rushed in pell-mell, stood up in the seats, hooted, called us names and threw spitballs, trying in vain to dislodge us.” Joanne Murray, Historian and Director at the Drexel University Legacy Center Archives and Special Collections, describes another account: “The men greeted the women students with yells, hisses, caterwauling, mock applause, offensive remarks on personal appearance, etc.”

The incident caught the attention of the press. “Newspaper articles about this incident nearly uniformly condemned the men for ‘ungentlemanly’ behavior,” says Murray. The Philadelphia Evening Bulletin called for expulsions and arrests of men who continued to harass the students in the streets. The public reproach wasn’t universal, however. A very different view came from a letter to the editor of the New Republic newspaper: “Who is this shameless herd of sexless beings who dishonor the garb of ladies?”

At a time of strictly observed gender roles, it was very rare for a woman to seek a medical education. In 1849—a year before WMCP opened—Elizabeth Blackwell became the first woman in America to earn a medical degree, from New York’s Geneva Medical College. Her initial application was subject to a vote by the all-male student body. Assuming that it was a joke, they all voted “yes.”

But Joseph S. Longshore had a different view. A Quaker, abolitionist, and physician, Longshore was a fervent believer in the importance of women’s education. Along with other physicians and businessmen*, he cofounded WMCP, and its first class included his sister Anna and sister-in-law Hannah. “That the exercise of the healing art, should be monopolized solely by the male practitioner … can neither be sanctioned by humanity, justified by reason, [nor] approved by ordinary intelligence,” he declared at the College’s introductory lecture.

WMCP opened in 1850, the first medical college for women. The idea of female physicians was welcomed by some, shunned by others. An editorial from the Boston Journal sniffed, “We consider the needle a much more appropriate weapon in the hands of woman than the scalpel or bistoury [curved surgical knife].” A Michigan newspaper took a more condescending approach: “We give our vote for a lady physician here—especially if a single lady, and therefore capable of administering a remedy for any disease of the heart that may occur.” Some male doctors argued in favor of separate terminology: Doctoress.

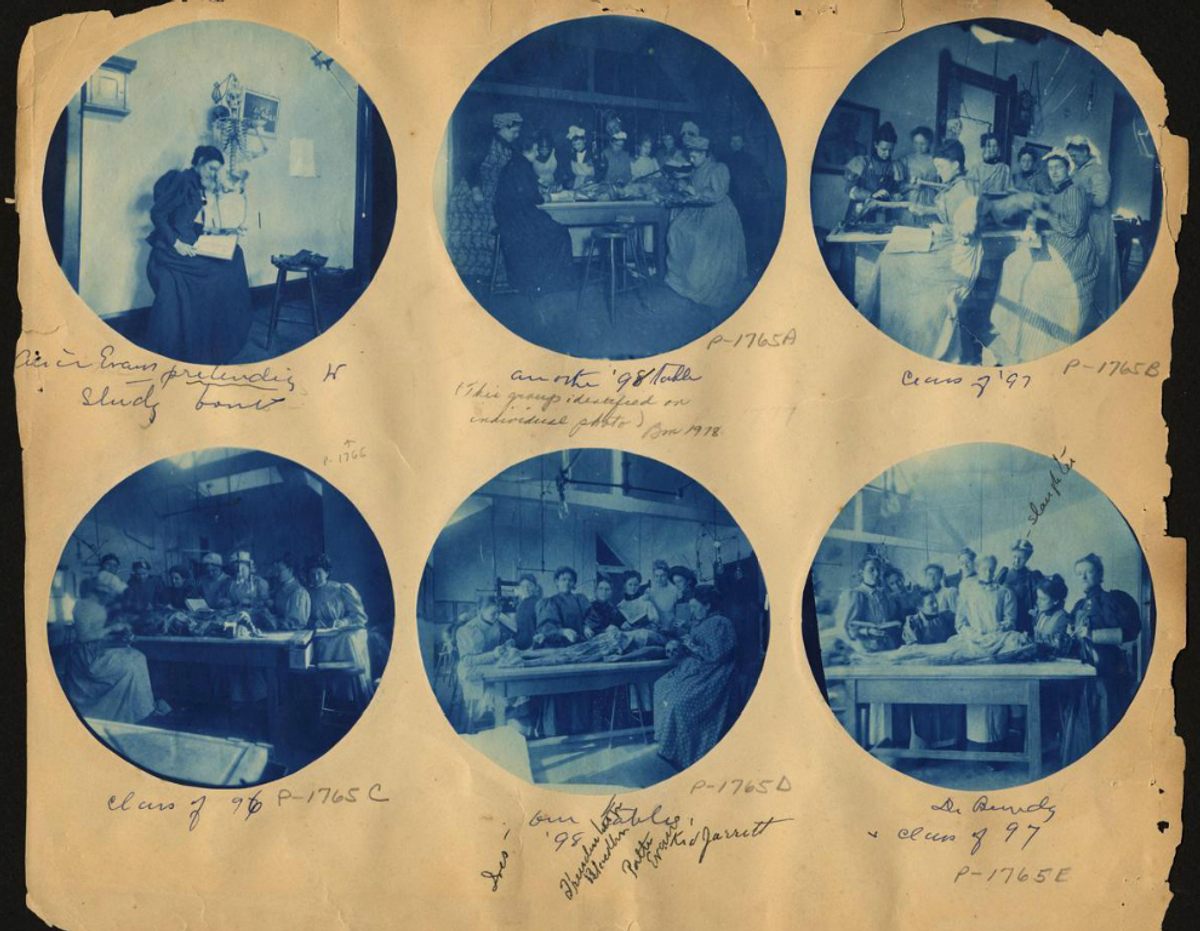

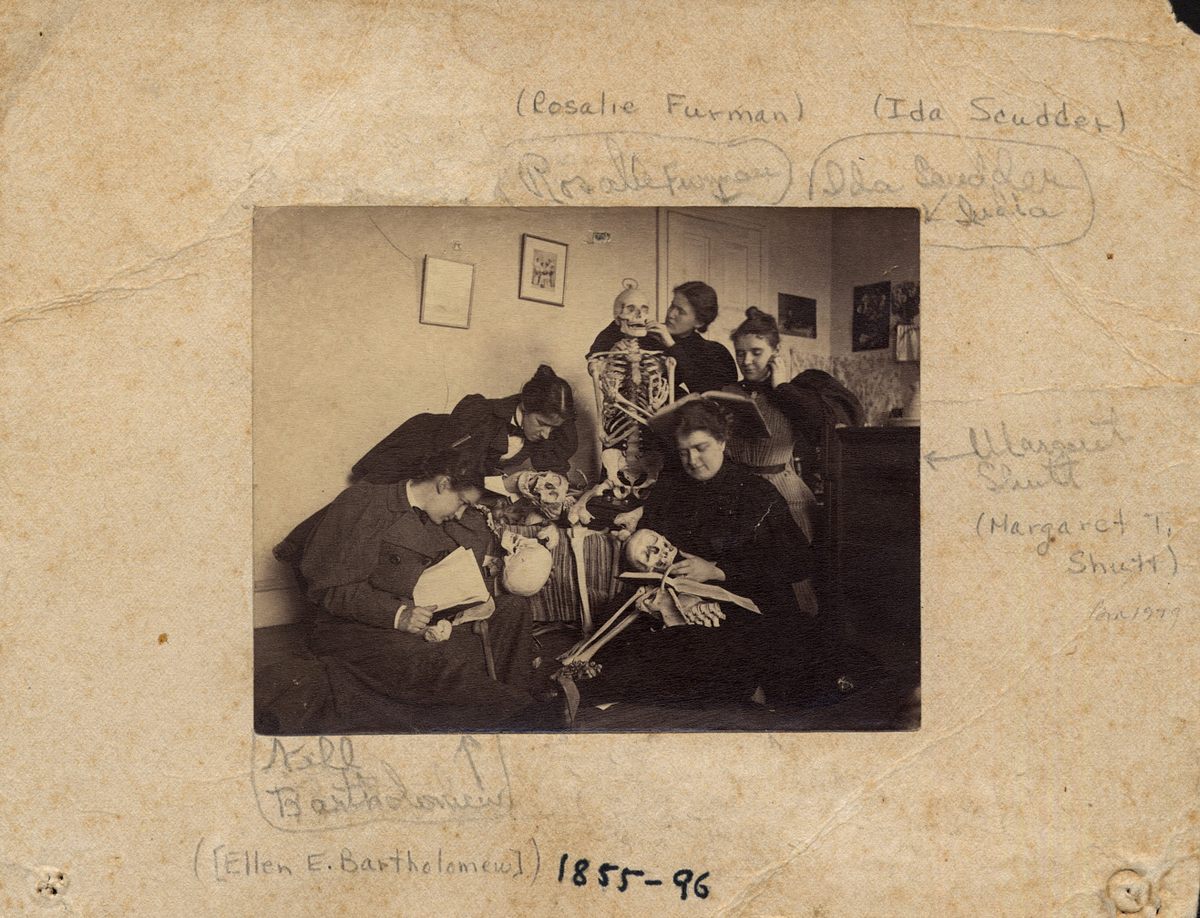

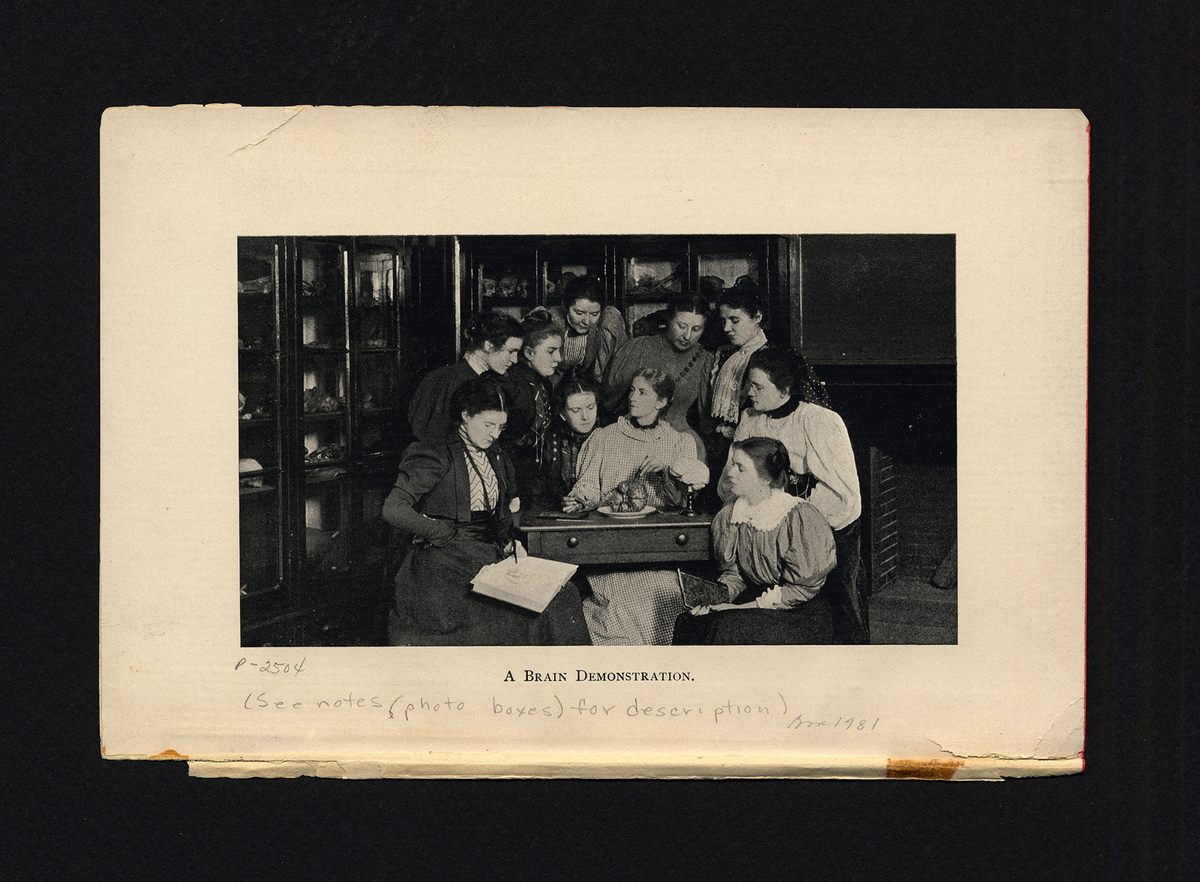

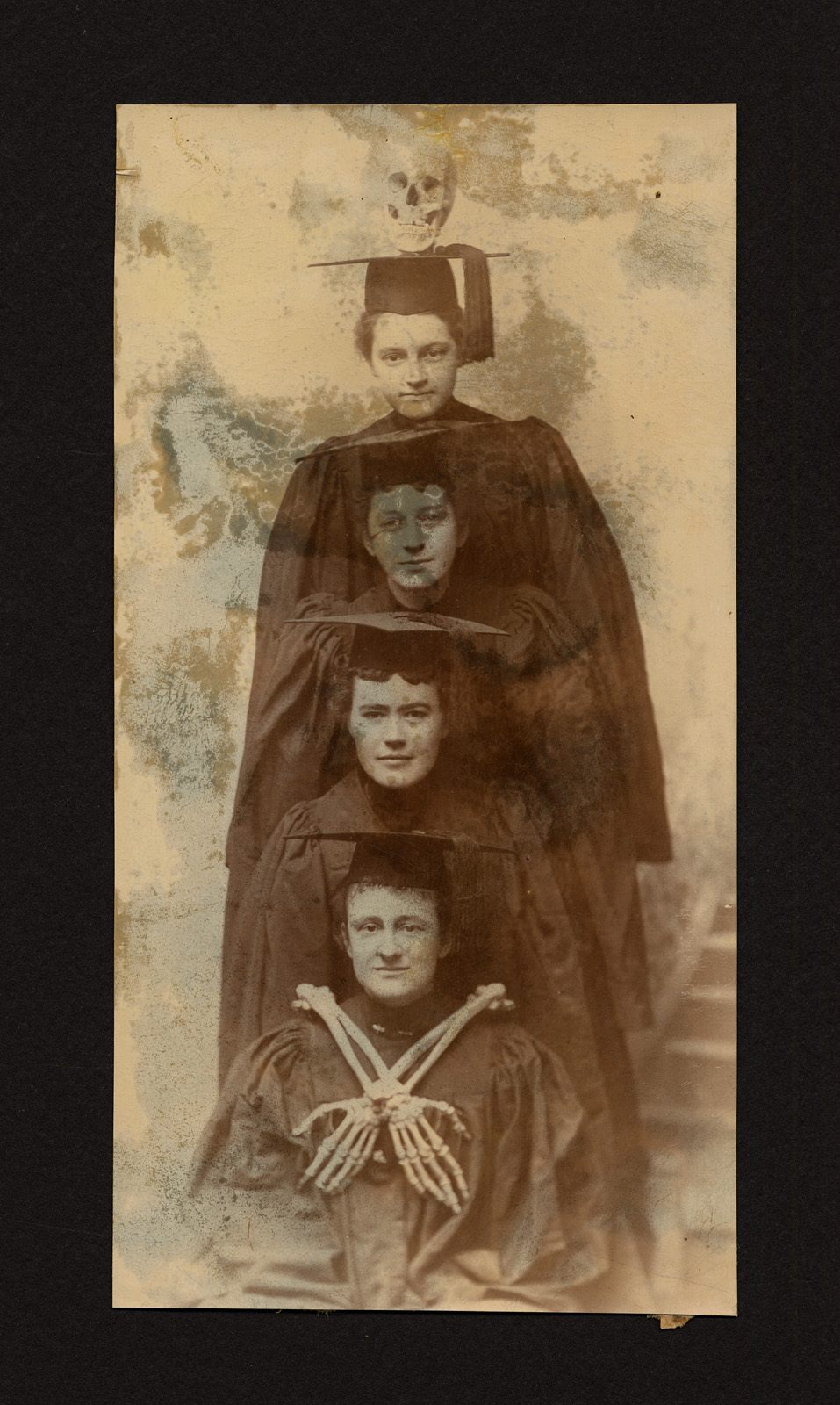

Despite the Jeering Incident, WMCP students continued to attend clinical lectures. They also participated in another essential aspect of medical training. “Women students learned through dissecting human cadavers as well, which of course was and is considered a rite of passage for medical students” says Murray. “But in the 19th century it was seen as a practice that women should not be undertaking. But the students generally valued the experience and even boasted about it to friends and family.” One student, Alice Evans, created a scrapbook with a page devoted to photographs of students mid-dissection.

Students at WMCP also worked with patients. They received clinical instruction at the Woman’s Hospital of Philadelphia after it was founded in 1861 (until that point, women had been barred from most hospital training). “A maternity practice gave students hands-on experience as they served an often-impoverished immigrant community in South Philadelphia,” says Murray. “They also learned at affiliated dispensaries, treating ailments such as measles, typhoid fever, and tuberculosis.”

The WMCP records are held today at the Legacy Center Archives at Drexel University. In 2002, Drexel absorbed the MCP Hahnemann University School of Medicine, which itself was once two medical schools: Hahnemann University and Medical College of Pennsylvania, the new name for WMCP after it became coeducational in 1970.

Combing through the Drexel Archives—either online or through its Twitter account—is a glimpse into a world that is both familiar and surprising. Students lounge in dorms and take notes in a lecture hall. But they also goof around with a skeleton, while others, in constrictive Victorian attire, prod at a brain on a table. “Photographs of women in 19th-century garb, complete with mutton chop sleeves and floor-length dresses, standing with their cadavers, can seem out of sync,” Murray says.

Even as many images seem to be mundane slices of medical school life, there are some particularly striking photos. “The 1885 photograph of three foreign women medical students dressed in the traditional style of their home countries is an image that surprises people all over the world,” says Murray. “It’s unusual enough to see photographs of 19th-century women doctors, but seeing a visual representation of the fact that women came to WMCP from foreign countries at that time is generally fairly shocking to most.”

The women in the photograph are Anandabai Joshee, who graduated in 1886, the first woman from India to earn a medical degree in America; Kei Okami, class of 1889, one of the first female physicians in Japan; and Tabat M. Islambooly, one of Syria’s first female doctors, who graduated in 1890. (She is also known as Sabat Islambouli, but very little else is known about her). A 1904 newspaper reported that WMCP’s alumnae include women from “Canada … Jamaica, Brazil, England, Sweden, Denmark, Switzerland, Russia, Syria, India, China, Japan, Burmah, Australia, and the Congo Free State.”

Another notable image shows the class of 1891. At the far right is Halle Tanner Dillon Johnson, an African-American student from Pittsburgh. She graduated WMCP with honors, and became the first woman to practice medicine in Alabama—but only after passing the 10-day Alabama State medical exam, described by The New York Times as “unusually severe.”

The first African-American student to matriculate at WMCP was educator and abolitionist Sarah Mapps Douglass, who enrolled in 1853. “She did not graduate, but she used her medical education to offer lectures and evening classes in hygiene and physiology to other African-American women,” says Murray. In 1867, Rebecca J. Cole graduated WMCP, and became the second African-American woman to receive a medical degree in the United States. (The first was Rebecca Crumpler, who graduated from the New England Female Medical College in 1864).

There were more milestones to come. In 1888 Verina M. Harris Morton Jones became the first woman physician in Mississippi. Eliza Ann Grier was an emancipated slave who put herself through medical school to become, in 1897, the first African-American woman licensed to practice in Georgia, and Matilda Evans, graduate of 1897, was the first African-American woman doctor in South Carolina.

Susan La Flesche Picotte was another pioneering WCMP graduate. Born on the Omaha Reservation in Nebraska, she saw, as a child, a woman die while waiting for a white doctor who never arrived. La Flesche Picotte graduated at the top of her class in 1889. She became the country’s first Native American doctor and returned to the Omaha Reservation to work.

The extraordinary achievements of these women occurred at a time of widespread racial and gender discrimination. Under the law at the time, La Flesche Picotte was not regarded as a citizen (and would not be until 1924). Not one of these women was able to vote.

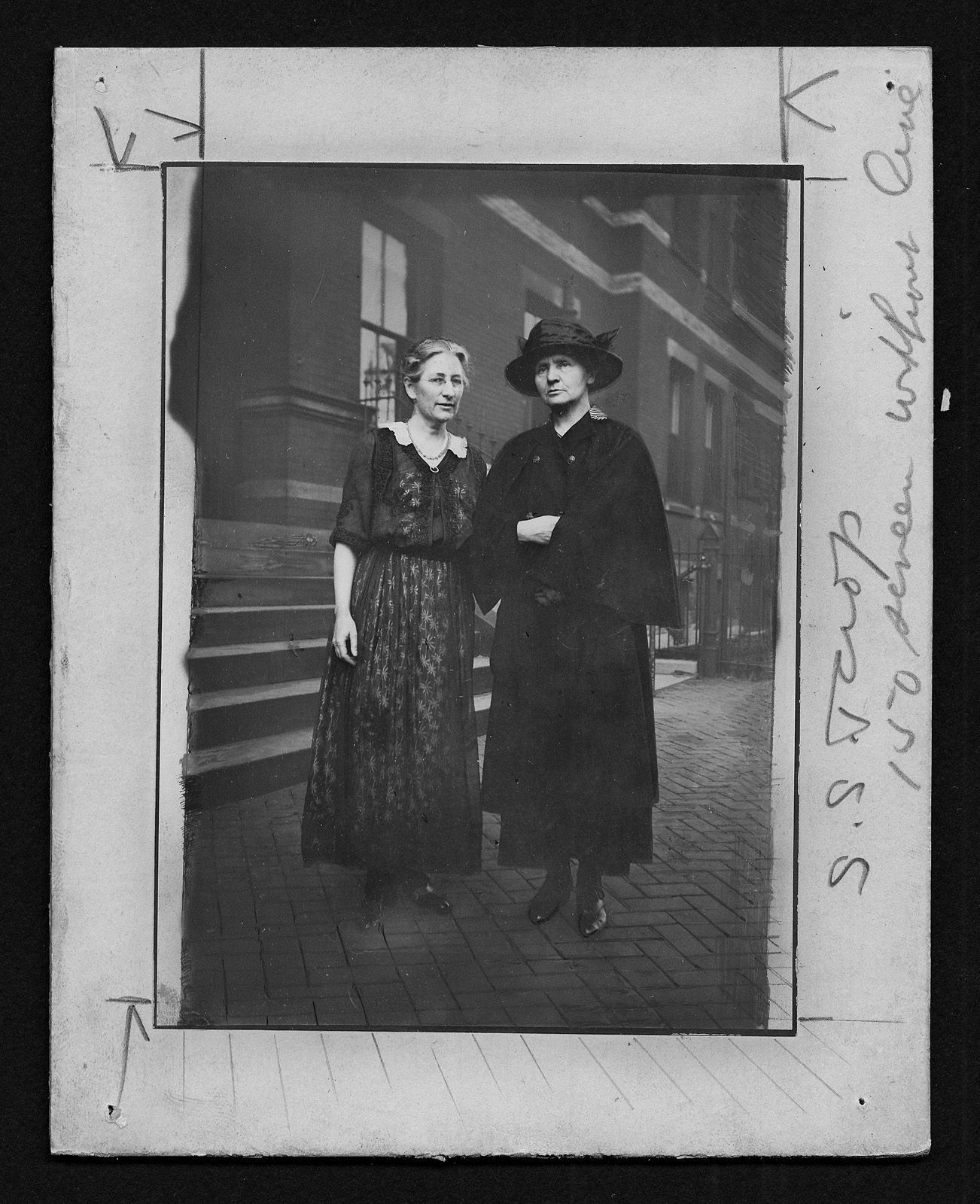

As WMCP expanded, so did its influence. In 1920, Marie Curie visited the campus and met with Dean Martha Tracy. “The photograph of the Dean and Madam Curie underscores the growing work of women in science and medicine and the support women leaders found in others like them,” says Murray.

Last year, for the first time, the number of women enrolling in medical school in the United States exceeded the number of men. Earlier in 2017, a New Yorker magazine cover depicting four female surgeons went viral and was replicated by female surgeons around the world with the hashtag #Ilooklikeasurgeon. Yet, despite the increased acceptance and visibility of women in medicine, there is still considerable wage inequality for women and minority doctors.

If we have moved from a place of jeering to a place of celebration, we can be thankful to the 19th-century women who first challenged the status quo. Recalling the harassment at that first clinical lecture, Broomall, who became a professor of obstetrics at WMCP, noted, “We went back. The disorder was renewed, but with diminishing violence, and at last the opposition wore itself out.”

* Correction: This article was updated to clarify that it wasn’t just Quaker physicians involved in the founding of the school.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook