The Improbable Life of the Inventor of the Modern Bra

She was also a pioneering publisher and, later, a princess.

Mary Phelps, known as Polly to friends, was born in 1891 to a family that could trace its heritage to such luminaries as William Bradford, Plymouth Colony’s first governor, and Robert Fulton, the inventor of the steamboat. As Northeastern* royalty, Polly grew up in New Rochelle, New York, wanting for nothing.

It wasn’t until 1910 that Polly realized something important was missing from her life. She was busy one day preparing for a debutante ball when she looked in the mirror and realized she loathed the way a corset made her look. It bunched up her bodice and squished her breasts into a single, uncomfortable monobosom. In her memoir, The Passionate Years, she referred to it as “a box-like armour of whalebone and pink cordage.”

Like all great innovators before her, necessity was the mother of Polly’s invention. She grabbed a handkerchief, ribbon, and a needle, and before the party was off the ground, had fashioned herself a new undergarment: the modern bra.

Polly wore her new bra to the party and turned heads. Not only was she wearing considerably less under her dress than most of the other women, she was also thrilled to tell everyone about it. Society may have been scandalized, but the girls went crazy for this new garment. So light! So comfortable! No whale bones making a stomach sandwich with your ribs! When a stranger offered a dollar to make her one of these new fangled backless brassiers, Polly realized she had a hit on her hands.

“That night at the ball,” Polly later wrote in The Passionate Years, “I was so fresh and supple that in the dressing room afterward my friends came flocking around. I gave them a peek and outlined the invention…From then on we all wore them.”

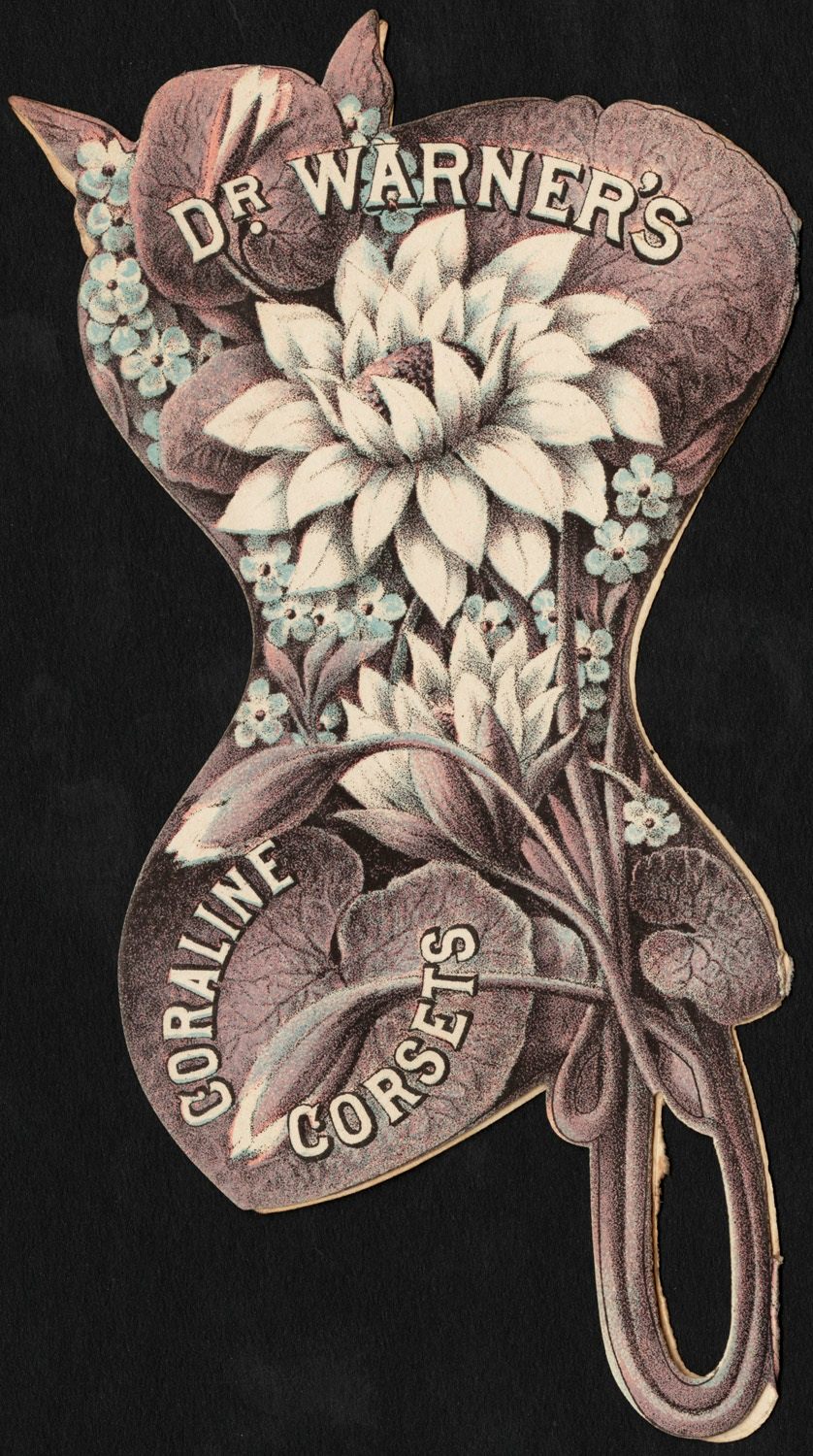

Bra-like garments go back to Ancient Egypt—Polly wasn’t the first to create one. In 1859, Henry S. Lesher invented a “breast pad and perspiration shield,” though his garment was torturous to wear. They were mostly made of rubber, making them hot, impractical, and uncomfortable. Another forerunner was invented by Luman L. Chapman. He created an improved corset, which included a sheet metal front clasp and “breast puffs,” which helped relieve the tightness of most corsets.

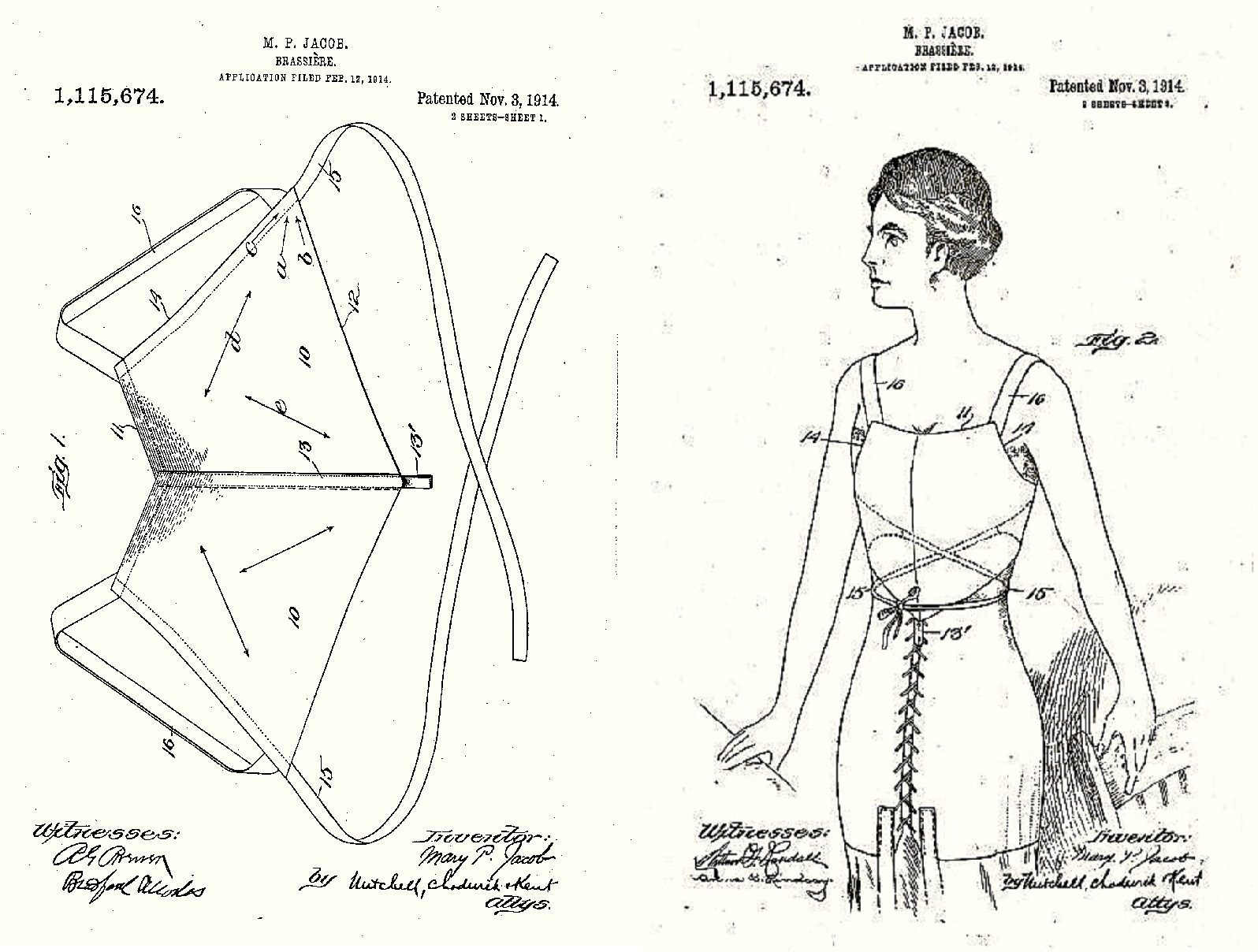

So Polly wasn’t the first to develop a more effective breast delivery system, but she was the first to file a patent on the forerunner to today’s wireless bra. Polly filed for a patent for her “backless brassier” on February 12, 1914, and it was granted in November of that year.

In her patent application, Polly wrote that her new invention was “capable of universal fit to such an extent that… the size and shape of a single garment will be suitable for a considerable variety of different customers” and was “so efficient that it may be worn even by persons engaged in violent exercise like tennis.”

With her patent in hand, Polly started the Fashion Form Brassiere Co., where she employed women to manufacture wireless bras. Another big reason the modern bra caught on? World War I. Unlike corsets, these brassieres required no metal. Metal was for war machines, not a woman’s cleavage. Polly’s patent was not only better for women’s health and fashion, but also for our boys abroad.

But before her invention really took off, Polly sold the patent to The Warner Brothers Corset Company for $1,500. Warner went on to earn more than $15 million from the bra patent over the next 30 years alone.

For most people, patenting the modern bra might be the crowning achievement of an otherwise ordinary life. But Polly had never been most people.

After her first marriage ended in divorce, Polly married Harry Crosby and the couple moved to Paris, where Polly decided to reinvent herself. She rechristened herself Caresse Crosby (she’d briefly considered calling herself Clytoris, but instead settled on naming her whippet that instead), and the pair vowed to live, what Harry called in a telegram home to Boston, “A mad and extravagant life.”

The Crosbys spent the next several years raising hell in the City of Lights. Together they opened a publishing company, Black Sun Press, and quickly amassed an impressive roster of authors including D. H. Lawrence, Ezra Pound, Lewis Carroll, James Joyce, Charles Bukowski, and Henry Miller. Time magazine would go on to describe Caresse as the “literary godmother to the Lost Generation of expatriate writers in Paris.” Black Sun Press became one of the most important publishing houses in Paris.

When not publishing, Caresse entertained Paris’s ex-pats with booze-fueled all-night sex romps that would have made Lord Byron blush. She and Harry bought an abandoned mill outside of Paris, named it “Le Moulin du Soleil” (The Mill of the Sun), and turned it into one the world’s greatest party venues. A plain, white wall functioned as their guest book—all famous guests were instructed to sign it on their way out. The wall was eventually destroyed during World War II, but we know such luminaries as Salvador Dali and D. H. Lawrence signed it (ironically, so did Eva Braun).

The Crosbys’ private lives were as wild as their social scene. Their open marriage led to affairs on both sides. Harry painted his fingernails, wore a black gardenia in a buttonhole, and had the bottoms of his feet tattooed. They bought their own tombstones, kept them on the roof of their apartment building, and grew fond of sunbathing naked on them. They roared around Paris in a green limousine convertible, with their whippets in the backseat wearing goggles.

The Crosbys’ marriage ended abruptly in 1929, when Harry killed himself in a murder-suicide pact with his mistress. His final entry in his journal, according to the author Geoffrey Wolff, read, “One is not in love unless one desires to die with one’s beloved. There is only one happiness it is to love and to be loved.”

Caresse took the million-dollar fortune left her by Harry and returned to America, where, in addition to Black Sun Press, she established Crosby Continental Editions, which published Hemingway, Faulkner, Dorothy Parker and others. She would go on to open an art gallery in Washington, D.C., star in several experimental dance films, and ghost write pornography for her friend Henry Miller. Caresse also married a football player 18 years her junior, then divorced him to romance a black boxing star, and later had an affair with the famous architect Buckminster Fuller.

At the age of 60, while on a tour of Italy, Caresse fell in love with a run-down castle near Rome named Castello di Rocca Sinibalda. She bought the castle, which came with a title, making her Princess Caresse Crosby. Caresse turned the castle into an artist’s colony for her friends, and spent the rest of her life dividing her time between its hallways and the U.S.

Caresse Crosby died in 1970, in Rome. Just before she died, a documentary filmmaker made a short movie about life in her castle. While giving him a tour, 70 year-old Caresse flashed the camera. No doubt her breasts were marvelously well supported.

*Update: We originally referred to Caresse Crosby as “New England royalty.” She grew up in New York, which is not part of New England.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook