One of the Earliest Science Fiction Books Was Written in the 1600s by a Duchess

Meet Lady Margaret Cavendish.

Margaret Cavendish, the Duchess of Newcastle. (Photo: Public Domain)

No one could get into philosophical argument with Lady Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne, and walk away unchanged. Born in 1623, Cavendish was an outspoken aristocrat who traveled in circles of scientific thinkers, and broke ground on proto-feminism, natural philosophy (the 17th century term for science), and social politics.

In her lifetime, she published 20 books. But amid her poetry and essays, she also published one of the earliest examples of science fiction. In 1666. She named it The Description of a New World, Called the Blazing World.

In the story, a woman is kidnapped by a lovesick merchant sailor, and forced to join him at sea. After a windstorm sends the ship north and kills the men, the woman walks through a portal at the North Pole into a new world: one with stars so bright, midnight could be mistaken for midday. A parallel universe where creatures are sentient, and worm-men, ape-men, fish-men, bird-men and lice-men populate the planet. They speak one language, they worship one god, and they have no wars. She becomes their Empress, and with her otherworldly subjects, she explores natural wonders and questions their observations using science.

And Cavendish starts it all by addressing the women in the audience. “To all Noble and Worthy Ladies,” she begins, and lets us know about the strange trip in store for them:

“The First Part is Romancical; the Second, Philosophical; and the Third is meerly Fancy; or (as I may call it) Fantastical. And if (Noble Ladies) you should chance to take pleasure in reading these Fancies, I shall account my self a Happy Creatoress: If not, I must be content to live a Melancholly Life in my own World, which I cannot call a Poor World, if Poverty be only want of Gold, and Jewels: for, there is more Gold in it, than all the Chymists ever made; or, (as I verily believe) will ever be able to make.”

But when Cavendish put her pen to paper, she didn’t just aim to tell a fun story. She also examined popular theories about science. In the 17th century, scientists began asking new questions about how the natural world worked, using the slide rule, telescope and microscope. Researchers dissected animals, interested in understanding their many parts. They also began to question the role of spirits, and God. Cavendish was fascinated by all of it.

The frontispiece for A Description of a New World, Called: The Blazing World, published in 1666. (Photo: Public Domain)

Cavendish “understands that fiction better accommodates speculation and imagination,” writes English professor Anne M. Thell in her essay “‘[A]s lightly as two thoughts’: Motion, Materialism, and Cavendish’s Blazing World”: and just like all good sci-fi, she uses her imaginative world to flesh out ideas about politics, mock and muse on scientific theories, and weave it all into a poetic landscape. In Cavendish’s literary world, souls can inhabit different bodies, man can’t comprehend God, and souls are genderless, traveling as thoughts on “vehicles of the wind.”

Growing up during the English civil war, Cavendish had an unusual upbringing for a woman in the 17th century. Described as a “shy” child, she lived for years with other royals in exile. But upon her return to England as a Duchess, she gained entry to a scientific world that most women of her time could not access. Her husband, who was also involved in natural philosophy, supported her interests and connected her with Thomas Hobbes, Robert Boyle, and René Descartes.

Cavendish was recognized as the first female natural philosopher, or scientist, of her time. She was also the first woman to be invited to observe experiments at the new British Royal Society, a forum for scientists, in light of her contributions to natural philosophy in her poems and plays. (Unfortunately, she was the last woman for over a century: a ban on women was soon instituted, lasting until 1945.)

Despite her shyness and “melancholic episodes,” Cavendish challenged society’s view of women, which made her subject to ridicule. She wore her own inventive style of dress, and was seen as too outspoken and bawdy for a true Lady. She not only believed in animal rights, she criticized values of her society, including its obsession with constant technological advancement. This, among other beliefs, earned her the nickname “Mad Madge.”

But none of that discouraged her from participating in natural philosophy. She wrote volumes, sending them to contemporaries in her field without shame. In The Blazing World, written six years after the British Royal Society formed, Cavendish’s protagonists question popular beliefs about the universe and use reason to examine scientific theories. The two main characters are both women, known as the Empress and the Duchess.

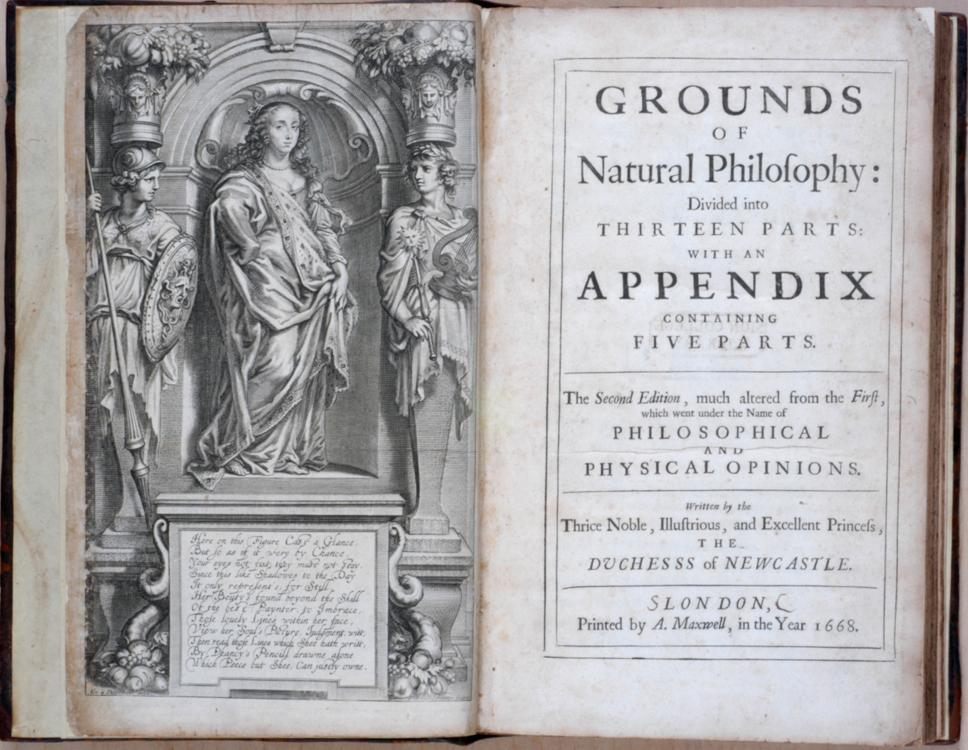

A portrait of Portrait of Margaret Cavendish, from the frontispiece to her 1653 work Poems and Fancies. (Photo: Public Domain)

Change some of the wording around, and The Blazing World resembles a modern science fiction story. While the Empress enters a “portal” in the book, today’s sci-fi tales might say she enters another dimension. The people of the Blazing World, as her universe was called, came in colors ranging from green to scarlet, and had what we might now call alien technology. Cavendish writes that “though they had no knowledge of the Load-stone, or Needle or pendulous Watches,” Blazing World inhabitants were able to measure the depth of the sea from afar, technology that wouldn’t be invented until nearly 250 years after the book came out.

As if that weren’t enough, Cavendish then describes a fictional, air-powered engine that moves golden, otherworldly ships, which she says “would draw in a great quantity of Air, and shoot forth Wind with a great force.” She describes the mechanics of this steampunk dream world in precise technical detail. All at once, in Cavendish’s world, the fleet of ships links together and forms a golden honeycomb on the sea to withstand a storm so that “no Wind nor Waves were able to separate them.”

The Empress is, of course, inquisitive. She employs the ape-men, worm-men and others to investigate how snow forms from water, and why the sun gives heat. Intellectual History professor Lisa T. Sarasohn notes in her book The Natural Philosophy of Margaret Cavendish that the Ape-men, the “chemysts” of the world, “foolishly waste their time trying to find the philosopher’s stone.” All at once, Cavendish criticizes science, politics and society at large.

In the middle of the story, when the Empress is offered the soul of anyone living or dead as a trusted advisor, she rejects Plato and Aristotle. Cavendish goes meta: she inserts herself as a character called the Duchess in her own book, and befriends the Empress as “platonic friends.” The Duchess and Empress then learn to create mini-worlds of their own using their thoughts.

Title age and frontispiece from Cavendish’s Grounds of Natural Philosophy. (Photo: Public Domain)

At one point the story becomes partly autobiographical: the souls of the Empress and fictional Duchess leave their bodies and travel from the Empress’ world to Cavendish’s home world, to counsel her husband by entering his body as spirits, in an effort to help him with his sociopolitical woes. As divisions and wars enter the plot, the Duchess wonders why her world “should prize or value dirt more than men’s lives, and vanity more than tranquility.” Back again in her own home world, the Empress then uses Blazing World technology to defeat enemies that threaten her country, using a “firestone” that explodes ships like bombs.

As Cavendish’s critiques of science mingled in her own fictional universe, she imagined a place where women could rule and were respected. She was well aware of the limitations placed on her gender, and as one of the first science fiction authors and characters, she was up for the challenge. “I am not Covetous, but as Ambitious as ever any of my Sex was, is, or can be,” she writes.

The reader is meant to conclude that when the beliefs of others do them no good, they might as well create their own worlds. And 350 years later, The Blazing World is still relevant.

Here’s the prologue written by Margaret Cavendish, Duchess of Newcastle-upon-Tyne and trailblazing sci-fi author, back in 1666:

“That though I cannot be Henry the Fifth, or Charles the Second; yet, I will endeavour to be, Margaret the First: and, though I have neither Power, Time nor Occasion, to be a great Conqueror, like Alexander, or Caesar; yet, rather than not be Mistress of a World, since Fortune and the Fates would give me none, I have made One of my own. And thus, believing, or, at least, hoping, that no Creature can, or will, Envy me for this World of mine,

I remain, Noble Ladies, Your Humble Servant, M. Newcastle.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook