The Art—and Anger—of Japanese Internment Camp Silk Screeners

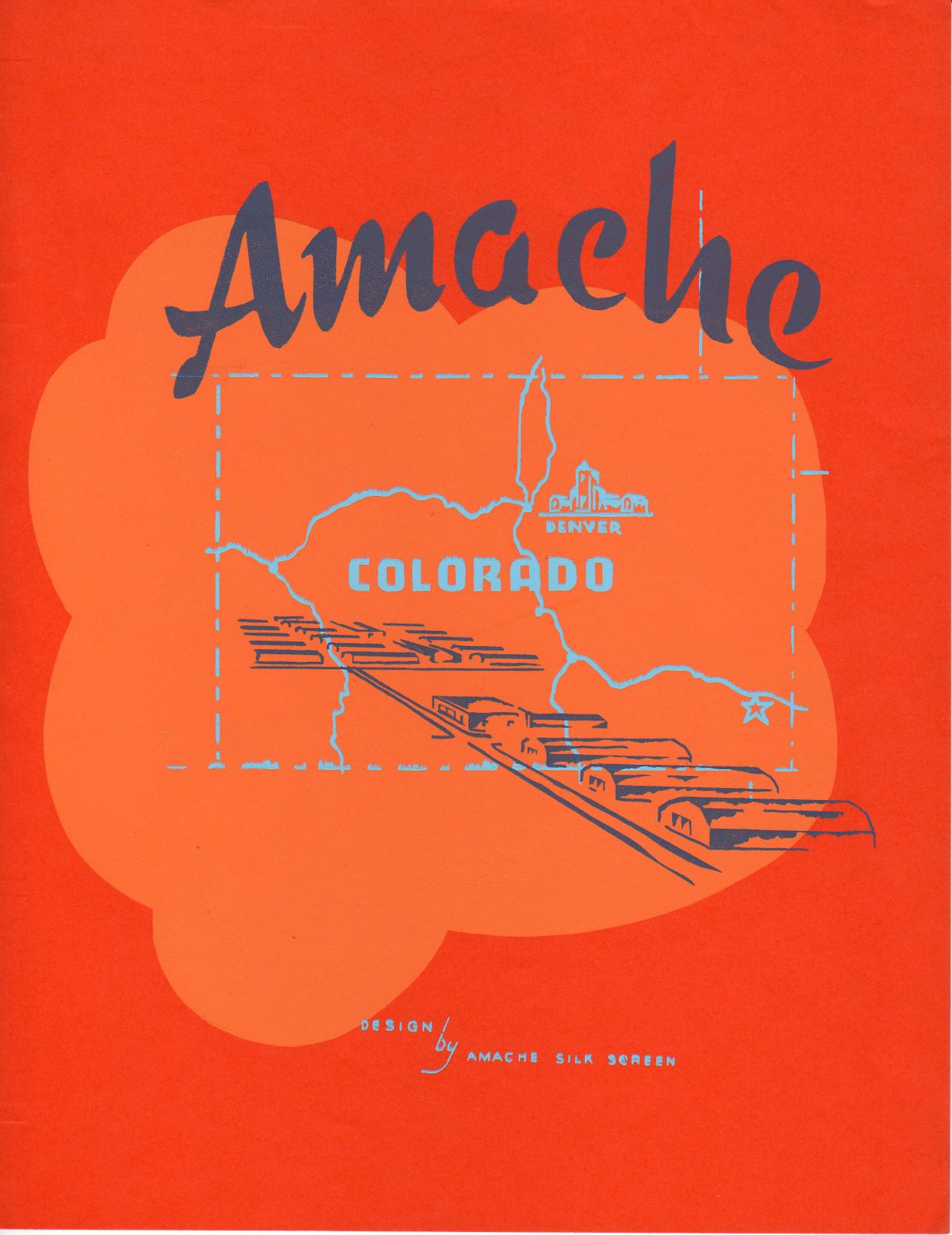

Inside the complex legacy of the print shop at Colorado’s Camp Amache.

In the late 1930s, Michihiko Wada—Mike to his friends and family—graduated from the University of Redlands, in California, and headed east to study engineering. Wada, a slim man with an easy smile, left most of his family—his parents, his sisters—out West. He began building his own life in New York, earning his graduate degree and setting off on what looked to become a promising career.

But then, in February of 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued Executive Order 9066. One by one, Wada’s family members received arrest warrants. His mother, Kuni, who taught at a Japanese language school, was named “a dangerous alien engaging in subversive activities” because she used textbooks approved by the Japanese government in her classroom. His father, the Baptist Reverend Masahiko Wada, was accused of “pro-Japanese sympathies and activities.” Both were sent to detention facilities in separate states.

Mike left his job in New York and headed back home, where he too was shipped off to an internment camp. After a short stint at a detention center in Wyoming, he ended up at Colorado’s Granada Relocation Center, also known as Camp Amache, with his two sisters, his brother-in-law, and his niece and nephews.

There, he temporarily changed careers. For two years, instead of pursuing his dreams, Wada—along with dozens of Amache detainees—worked as a professional artist at the Amache Silk Screen Shop, printing posters and pamphlets for the U.S. military, the very entity that was imprisoning his entire family.

“He came back from New York knowing full well he would get swept up in the evacuations,” says Mitch Homma, Mike’s great-nephew. In 2006, Homma found his great-uncle’s silk screen work—and many letters, records, and pieces of camp paraphernalia—packed in boxes in his grandmother Mutsu’s closet. Mike Wada’s photos and prints—along with those of the few dozen artists who worked at Amache Silk Screen Shop—make up a bittersweet historical record, shedding color and light on one of America’s darkest eras.

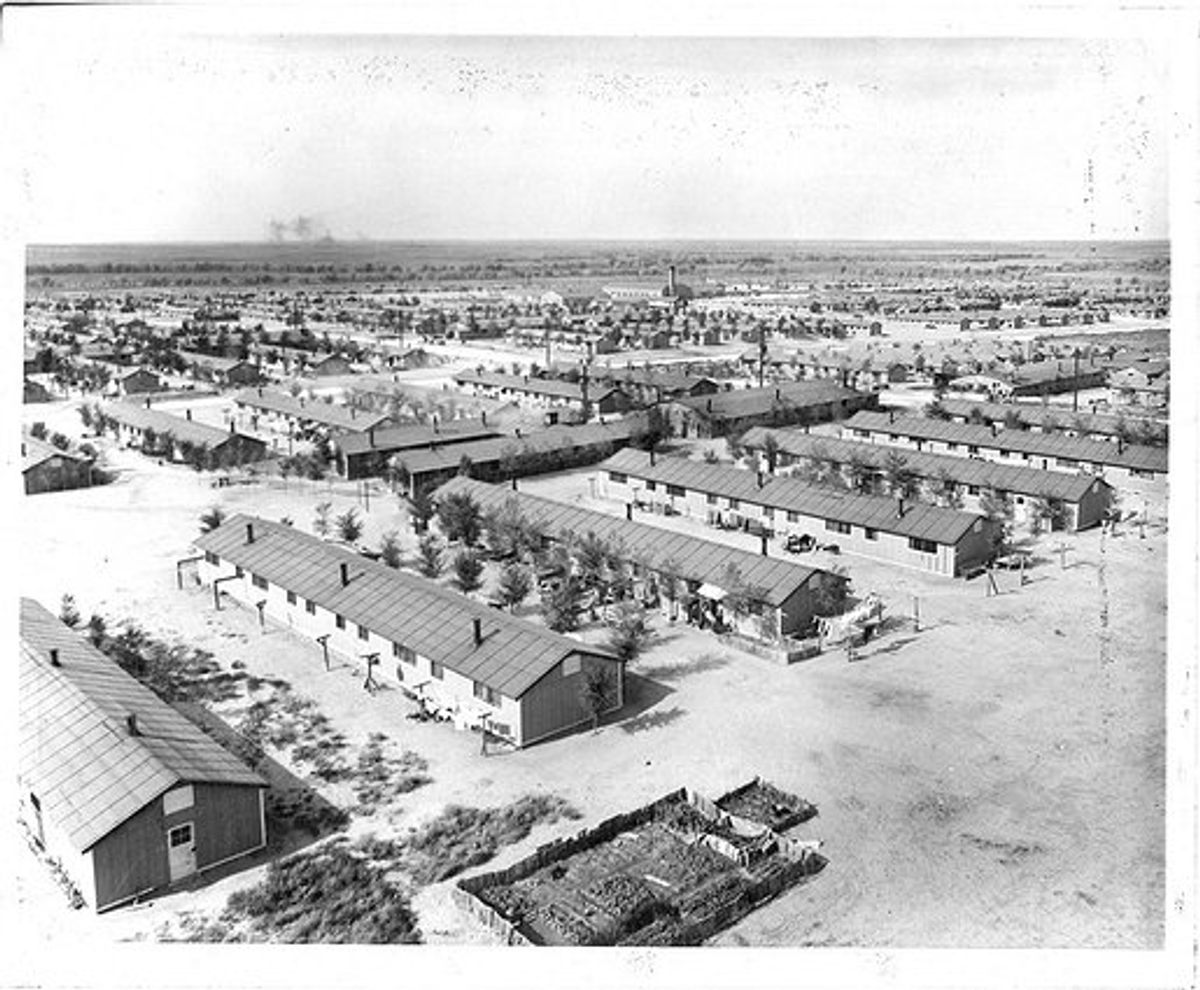

As the historian Melvin Yazawa explains in his history of Camp Amache, the Western “relocation centers” that housed 120,000 detainees were constructed hastily. There were a few War Department employees assigned to each camp, in charge of administrative work. But for the most part, it was left to the internees—who generally came to the camps on about a week’s notice, with few to no possessions—to piece together various community institutions, based on guidelines set by the War Relocation Authority, or WRA.

When the first prisoners came to Camp Amache, in August of 1942, only a few of the barracks were habitable, and there was no running water. By the time Mike Wada got there about a year later, the camp had a mess hall, a school system, a hospital, a post office, police and firefighting forces, and an elected community council. A look through the Granada Pioneer—Camp Amache’s biweekly, bilingual newspaper, itself staffed by internees—details an energetic schedule of camp events, including basketball games, school dances, film screenings, and the occasional carnival.

Amache also had something unique among the camps: a successful silk screen shop. As the war ramped up, the U.S. Navy found themselves with boatloads of new sailors, and—due to the wartime labor shortage—no one to print the posters, charts, and other materials necessary to train them. In the spring of 1943, Maida Campbell, a Red Cross nurse with an artistic background, was sent to Camp Amache to see whether it would be feasible to open a printing operation there.

Campbell set up the shop in a recreation hall, and began advertising in the Pioneer for employees. A month into their work, the Pioneer reported that the shop’s 25 artists had printed “some 185 large posters, 250 stickers, and 100 cards,” for practice. By August, they had their first order from the Navy, for four posters that depicted “motives for enlistment.” Over the course of 1943, the shop printed at least 120,000 posters in dozens of designs, depicting everything from signal flags to principles of seamanship. Employees took on the entire process, from design and stenciling through color selection and printing.

“Because the shop is in a War Relocation Authority center, we have more problems than the average shop,” wrote Campbell in an introductory booklet. As she explains, printing was often interrupted by everyday tasks, such as haircuts and doctor’s appointments, which could only happen during working hours, when the camp’s other amenities were available.

But for the workers—and the internees in general—the main problem was the Colorado dust. “The walls would seep sand and dust, it would come up through the floor,” says Homma, whose father—Mike Wada’s nephew, Hisao Homma—spent three years of his childhood in the camp. The 1943 April Fool’s issue of the Pioneer jokingly reported a monthly dust forecast of “about 750 feet.” If a windstorm kicked up, the shop had to be abandoned, lest the wet posters get coated in it.

The dust was but one unsettling aspect of a place that was, essentially, a massive interruption. As Yazawa writes, most internees had been forced to evacuate their homes extremely quickly. Many lost their jobs, possessions, and homes while they were gone. “It changed our family forever,” says Homma, whose relatives started anew in Seattle after they were released.

Although silk screening jobs were in demand, the shop wasn’t immune to further injustices. The pay topped out at $19 per month, about half of what one could expect to receive for similar work outside. Despite Campbell’s evident respect for her employees, she, like other administrators, wrote frequently about how the shop provided “vocational training” for them—never mind the fact that their detainment at the camp was preventing them from pursuing their actual vocations, hobbies, and lives.

Still, the workers made the most of it. When there were no Navy orders to fill, the artists turned their skills toward helping the community. The silk screen shop took every opportunity to brighten up ordinary camp materials, printing brochure covers, Thanksgiving menus, food production guideline posters, concert programs, and the annual high school yearbook, among many other items.

On Christmas Eve, 1943, the artists trekked around camp, hand-delivering a special calendar they had designed and pressed in 20 colors. The shop also offered to print diplomas for graduates of every camp school in the country—although it’s unclear whether the plan ever went through—and fielded a basketball team (which, according to the camp’s sports pages, tended to trounce the Pioneer’s team). “That’s very Japanese,” says Homma. “You work for the good of the community, and you give back to the community.”

Artists also pursued their own projects. In their first days, to learn the silk screening process, each new employee drew a bookplate, Christmas card, or letterhead, and took it through the whole workflow. Some artists exhibited their work in camp shows, while others drew comics for the Pioneer.

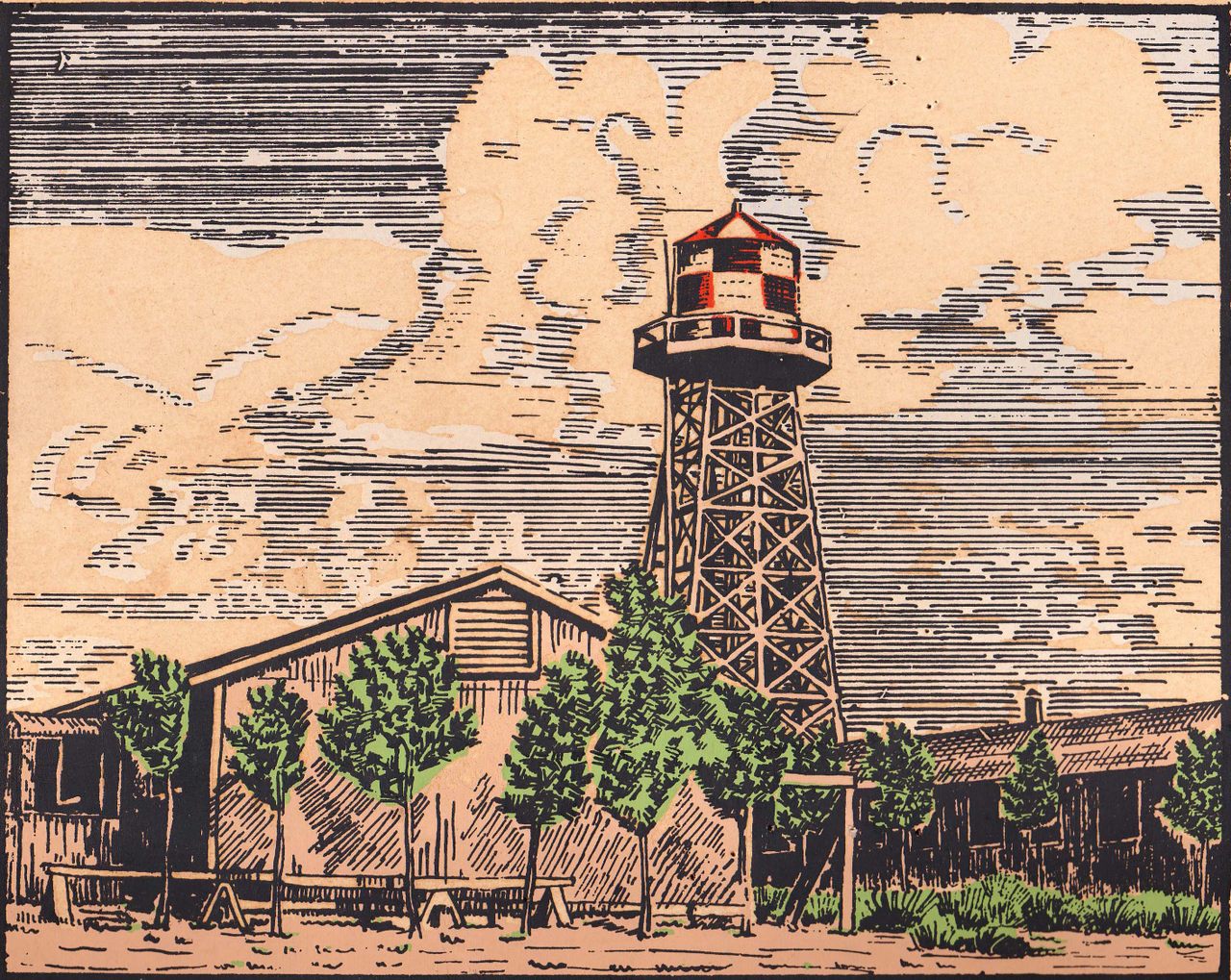

Mike Wada, who worked in the shop darkroom, immediately took to photography. Although internees technically weren’t allowed their own cameras, he was able to practice in his off-hours thanks to his brother-in-law, Dr. Kyushiro Homma, an avid photographer who had brought some along in his capacity as camp dentist. Wada’s photograph above, of the camp’s imposing water tower, was reimagined in the silk screen shop as the frontispiece of the camp Christmas calendar, and is probably the best-known print to come out of the shop.

Over its two-year tenure, the Amache Silk Screen Shop doubled in size, eventually employing 50 people. (The employees at one point had to renovate a second recreation hall to fit everyone.) And after a second shop, at Wyoming’s Heart Mountain Camp, failed to get off the ground, the Amache crew inherited all of its equipment. By the time the shop shuttered, in May of 1945, its artists had printed over 250,000 posters.

In the meantime, Wada, like the rest of the country’s detainees, had lost years of his life. He’d also lost his brother-in-law and mentor, Dr. Homma—Mitch’s grandfather—who shed 50 pounds over the course of his incarceration, and died of a heart attack and stroke in August of 1944. For decades, Wada and his family also lost the will to talk much about their experience. “When I was growing up, and I heard people talking about camp, I thought they meant church camp,” says Homma. It took until the aftermath of the September 11, 2001, attacks, when the U.S. government began detaining some Muslim people, before most survivors Homma knows began speaking up about their experiences, he says: “They were always told it wouldn’t happen again.”

Mike Wada went back to New York and became an engineer; by the time he died, in the late 1980s, he was the Vice President of Mitsubishi Aircraft Industries. Like many people who took up creative work in the internment camps, he never silkscreened anything again. He did bring one thing with him, though: “All his life he was an avid photographer,” says Mitch.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook