How a Location Scout Spends 3 Days Touring L.A.

Nick Carr shares his favorite Hollywood backdrops for Three Obscure Days in Los Angeles.

The history of Los Angeles’ dominance in the entertainment industry involves a trope older than Hollywood itself. East Coast-based filmmakers longed for the year-round sunshine of Southern California.

The other major reason nearly all of America’s early film studios ended up in L.A. was to escape the iron grip of Thomas Edison’s Motion Picture Patents company, which made it nearly impossible for filmmakers to work independent of Edison. Across the country in California, the inventor’s patents weren’t enforced.

But Los Angeles didn’t just offer mild weather and artistic (and legal) freedom. “Within a 30 or 40 mile radius, you have desert, you have beach, you have mountains, you have city, and you have suburbia,” the location scout Nick Carr explains. “You have everything.”

For storytellers, Los Angeles’ diverse terrain offers endless possibilities. Since cinema first took root in the city around 1912, the relationship between filmmaking and Los Angeles has been symbiotic. On a micro-level, mini-transformations take place on a daily basis, when buildings, blocks, or patches of wilderness are made to look like far-flung locales. On a macro-level, the city has evolved into the metropolis it is today because of its widely diverse landscapes.

In 2015, Carr—known for his blog Scouting New York and now, Scouting L.A.—moved from New York to Los Angeles and “never looked back.”

Carr spends his days driving through Los Angeles, sizing up the smallest of details and weighing careful, logistical considerations in search of real places that suit fictional universes.

It doesn’t happen often, but sometimes, a location itself becomes the star of a film. “Storytelling elevates these places to mythic status,” Carr says. And even when it doesn’t, there’s nothing quite like stumbling on a place and finding out that one of your favorite movies was filmed there. This can happen anywhere, but it happens all the time in Los Angeles.

Following Carr’s lead, we’ve put together a three-day itinerary featuring some of Los Angeles’s most iconic shooting locations. While some are well-known pilgrimage sites for film buffs, others are inconspicuous reminders that, like the most skilled of actors, Los Angeles can take on any role.

Day 1 Agenda:

-

Start the day at Point Dume

-

Visit Western Town at Paramount Ranch

-

Explore the ruins of Peter Strauss Ranch

-

Have Dinner at The Old Place restaurant

Point Dume

For a city of its size, it’s remarkably easy to escape the bustle of Los Angeles. Begin the journey at the city’s westernmost edges, in Malibu. Seclusion, scenery, and terrain have made this beach community irresistible to filmmakers since the 1960s.

Point Dume is a promontory that dramatically rises above the surrounding sands, walling off either side of the beach. It’s as stunning a sight as it is surreal, making it the perfect location for the ending scene of the original Planet of the Apes.

Charlton Heston’s character, having escaped his primate captors, walks along an alien shoreline when he sees a crumbling Statue of Liberty wedged among the rocks in Point Dume. The twist is that he’d been on earth this entire time. If the ending sounds like a Twilight Zone episode, it’s not a coincidence: Rod Serling co-wrote the screenplay.

It may seem odd that filmmakers chose a recognizable natural landmark to capture a scene that should have taken place in New York. But Point Dume’s size obscures the scenery behind it, making the location difficult to pinpoint. Point Dume was largely uninhabited until shortly after WWII, and the first school didn’t open there until 1968—the year Planet of the Apes was released. It’s safe to say that the location wasn’t recognizable yet.

In the years that followed, Point Dume became a popular shooting location. Planet of the Apes was its big break.

Paramount Ranch

A short drive heading east will bring you close to Paramount Ranch, a former “movie ranch”-turned national park that delivers on everything its lofty name promises.

In the early 1920s, when Westerns were rising in popularity, a number of studios purchased ranch locations to shoot outdoor sequences. One of these was Paramount Ranch. During the golden age of cinema, just about every screen legend you can imagine filmed on Paramount Ranch’s versatile grounds, which were used for more than just Westerns. Paramount Ranch filled in as the Sahara desert in the Marlene Dietrich vehicle Morocco, and Ancient Rome in Cecil B. DeMille’s epic The Sign of the Cross.

Though Paramount eventually sold the lot, a portion of it was saved in the 1950s by a retired Western-lover and his son. Together, they built Western Town to encourage filmmakers to continue making the films they loved there. Located at the park’s entrance and open to the public to explore, it remains Paramount Ranch’s most visible attraction, though the park also beckons with its miles of storied trails and beautiful views of the Santa Monica mountains.

A second revitalization in the late 1980s has kept Western Town buzzing to this day. In the 1990s, it served as the main setting for Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman. More recently, you might recognize it as Westworld’s town square.

Peter Strauss Ranch

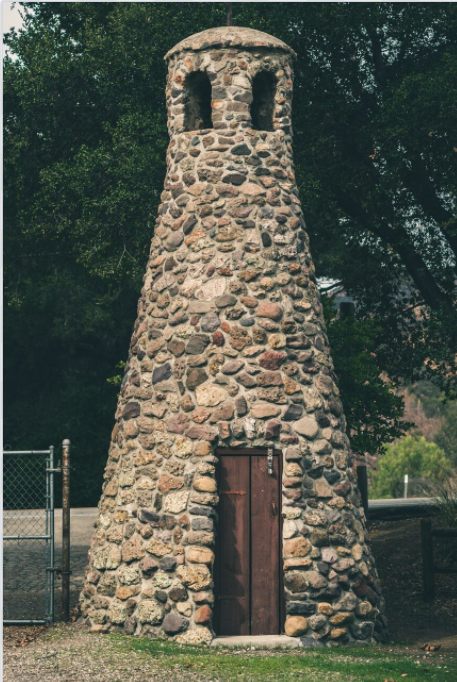

Just about two miles from Paramount Ranch, Peter Strauss Ranch is a historic gem you wouldn’t necessarily guess you could access. Auto businessman Harry Miller bought this land as a weekend retreat in 1923, building a ranch house, aviary, and stone tower, all of which are still standing.

Legend has it that Miller used the elfin tower at the ranch’s entrance as a lookout whenever he hosted one of his notorious Prohibition-era parties.

Miller sold the ranch in the midst of the Great Depression, and the area was soon developed into an amusement park and resort called “Lake Enchanto” (a portion of the Malibu Creek on the premises was dammed, creating an eponymous body of water). At one time, the park boasted the largest swimming pool west of the Mississippi. A miniature amphitheater built during the same time hosted musicians including Johnny Cash and Willie Nelson.

The park eventually closed in 1960. In 1976, the actor Peter Strauss bought the ranch, restored it to a more “natural” look, and then sold it back to the Santa Monica Mountains Conservancy a decade later. Though it can be traversed in under an hour, it’s worth it to spend some time in this strangely serene, whimsical place.

The Old Place restaurant

Directly across the street from Peter Strauss Ranch is the Old Place restaurant. Its weathered wood facade topped by a massive pair of antlers could fool an unappreciative eye into thinking they’ve come upon an Old West-themed restaurant. But the Old Place is the real deal.

In the 1960s, Tom Runyon bought a decrepit general store with the dream of transforming it into a restaurant. If his name sounds familiar, you’re not mistaken. He grew up shooting pigeons and raising falcons on his father’s land, Runyon Canyon.

Runyon carefully selected salvaged materials to build his restaurant. The 30-foot bar was transported from a saloon in Virginia City, Nevada on his private bomber (he had served as a pilot in WWII), and the stool that surrounds it is an antique diving board. Virtually every square inch of the Old Place tells a story.

The location’s closeness to Paramount Ranch ushered plenty of actors through the Old Place’s swinging doors. A part-time fiction writer, Runyon’s love of storytelling endeared him to the actors and filmmakers who frequented the restaurant. A display in the back of the restaurant details Runyon’s friendship with luminaries such as Sam Peckinpah and Steve McQueen.

After Tom Runyon passed, his son Morgan inherited the place. There are a few more items on the menu these days (in the beginning, the restaurant only served steak and clams), but the place has preserved an aura of reticent charm in step with the silver screen cowboys who used to congregate there.

Day 2 Agenda:

-

Stay at the Millennium Biltmore hotel

-

Visit City Hall’s Observation Deck

-

Stroll through Union Station

The Millennium Biltmore

After a day spent hiking in Malibu’s “wild west,” begin the second day of your trip by waking up in a place that epitomizes Hollywood glamour. It may feel strange, but Carr experiences this sort of discombobulation everyday.

“One day I’m scouting underground subway tunnels, the next day I’m looking for a hidden lake in the mountains, the next day I’m trying to find a beach for a surfing scene…my office changes every single day,” he says.

The ultimate arbiters of pomp, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences was founded at a luncheon banquet at the Millennium Biltmore in 1927. According to legend, the MGM art director Cedric Gibbons sketched the Oscar statue that we know today on a napkin, on the spot.

When it was built in 1923, the Millennium Biltmore was the largest hotel in the United States west of Chicago. Its design is a catalogue of Baroque European influences. From the palatial ballrooms crowned by massive chandeliers to tiny mosaic tiles that depict mythical figures, the Millennium Biltmore is as awe-inspiring as it is tantalizing in its details.

Beyond its history with the Academy Awards (it hosted nine ceremonies in total), the Biltmore has, unsurprisingly, always been a popular filming location. It may be most recognizable as the site of the Ghostbusters’ battle with the green “Slimer.” If the connection doesn’t strike one immediately, it’s no surprise: we think of Ghostbusters as taking place in New York. It’s clear that the filmmakers were on the hunt for a grand hotel to host the gross battle sequence for comedic effect, and the Millennium Biltmore fit the bill.

If you stay at the Millennium Biltmore, don’t miss one of its most wonderful, hidden features: an underground health club designed in the style of 1920s luxury ocean liners. The turquoise-hued pool is surrounded by subtle Grecian features, including figurative tiles and gold-capped columns. The deck chairs that line the pool would look at home on the Titanic.

In the 1999 film Cruel Intentions, Reese Witherspoon and Ryan Phillippe take a dip in the Biltmore’s pool, where it’s intended to look part of a country club. Filmmakers didn’t even need to disguise the set. Hidden beneath the Biltmore and having preserved its continental, 1920s design, it betrays no sign of its location.

Union Station

An itinerary featuring filming locations in Los Angeles wouldn’t be complete without a nod to Blade Runner. Perhaps more than any other film, Blade Runner has enthralled moviegoers with its surreal depiction of Los Angeles in 2019.

Ridley Scott achieved this uncanny affect by choosing well-known Los Angeles landmarks (including the Ennis House and Bradbury Building) and filtering them through a lens of dystopian gloom. Anyone who has ever stepped into the bright, magnificent interior of the Bradbury Building knows of the transformative powers Scott was able to conjure in his vision of the not-too-distant future.

In Blade Runner, Union Station is cast as a dark, barren, police station—one so large that it suggests the concepts of law and order may be bygone relics. We never see the station’s exterior, for good reason: it’s too beautiful. The stunning structure is a combination of Mission Revival, Streamline Moderne, and Art Deco influences. It’s flanked by sky-high palm trees, and looks exactly as you would want a Los Angeles train station to appear.

The interior is just as impressive, with its teak ceilings, waiting areas lined with distinguished leather chairs, and Navajo-inspired tiled flooring. Though it may not see the traffic it did before air travel took off, a visit to Union Station quickly dispels the myth that Angelenos only travel on four wheels. The station bustles as a public transit station and an Amtrak hub that takes riders up the coast and down to Mexico.

Beyond Blade Runner, Union Station has played a more conventional role in plenty of productions, including Catch Me if You Can and Drag Me to Hell. Even if you’re not en-route to another destination, Union Station is a must-visit for anyone with an appreciation for architecture, not to mention film history.

City Hall

“There’s this feeling of L.A. as a dueling ground for police and safety versus corruption,” says Carr. “If you’re going to tell that story, you’re always going to find a way to put city hall in the background.”

As storytellers since time immemorial have shown, there are many ways to tell the story of good versus evil. But the method that Carr describes is specific to Los Angeles, and can be credited in large part to writers like Raymond Chandler. In the 1930s, film noir authors and filmmakers introduced the world to a Los Angeles that was equal parts seedy and sultry. The 1997 neo-noir L.A. Confidential tips its hat to this legacy and features City Hall in its background.

Associations aside, City Hall may be most recognizable for its role in another tale of good versus evil. In the 1950s, it served as the Daily Planet headquarters for the original Superman TV series.

City Hall is worth a pilgrimage for film fans, but its most delightful feature has nothing to do with movies. Taking the elevator up to the 27th floor, one enters a grand banquet hall with floor-to-ceiling windows draped in red velvet curtains and a dizzying, geometrically patterned ceiling. Stepping outside, there’s a viewing platform that offers a 360-degree panorama of Los Angeles that’s breathtaking to behold.

Directly beneath the banquet hall and viewing platform, the Mayor Tom Bradley room features portraits of Los Angeles’s mayors since the city’s genesis. It may appear staid in comparison to the majesty of the 27th floor, but a closer look yields a semi-comprehensive history of the city’s development. Superbly written panels contextualize each portrait, reminding one of the continuous struggle for power and justice in the city.

Day 3 Agenda:

-

The Gamble House

-

Pee-wee Herman’s House

-

Michael Myers’ House

-

The Luggage Room/La Grande Orange Cafe

The Gamble House

“L.A. is fantastic at being everywhere,” says Carr. On day three, spend your time exploring a city that may exemplify this more than any other place in the metro area: Pasadena.

The Gamble House is often referred to as a masterpiece of Arts and Crafts architecture, a movement focused on traditional craftsmanship that incorporated medieval, romantic, and folk styles of decoration. It originated in Britain and spread through North America, eventually reaching Japan in the 1920s. The Gamble House’s Japanese influence in particular (or at least, an American’s interpretation of Japanese influence) is evident in the structure.

Back to the Future fans will recognize it as Doc Brown’s house. But whether you’ve seen the film or not, the three-story, 6,100-square-foot structure will make you want to pull over. It’s beautiful yet imposing, bizarre but slightly somber. In other words, the perfect residence for a madcap scientist.

Due to the delicate nature of the preserved home, filming of the interior actually took place at another residence. But luckily, today the Gamble House is a museum that is open for tours. If you go, consider taking a bar of soap: the house’s name comes from its original owners, the Gambles of Procter & Gamble. Visitors have been gifting soaps to the house for years, and a small cupboard displays their labels through the ages.

Pee-wee Herman’s House

Another madcap adventurer who resided in Pasadena was Pee-wee Herman. But unlike the Gamble House, Pee-wee’s abode is easy to miss.

White picket fences are supposed to symbolize suburban perfection, but the crooked fence that stands in front of this white house resembles a jagged grin. The place is nearly unrecognizable without its fire-engine paint and fanciful lawn sculptures, but the fence in particular is a signifier of what the director Tim Burton saw in his original vision: he wanted a house that resembled a face.

“There are the locations that have obvious artistic value or cultural merit, but then there are the ones like Pee-wee Hermann’s house, which is just a house,” Carr explains. “But because of it’s connection to our shared cultural history, it’s a house that’s beloved by the world.”

Pee-wee’s cult following is strong to this day. Discovering that an otherwise unremarkable house once in fact belonged to the fictional character could be the highlight of your trip.

Michael Myers’ House

Like Pee-wee Hermann’s house, the childhood home where Michael Myers murdered his sister in Halloween isn’t instantly recognizable (aside from a terrifying Michael Myers dummy that its owners have hung from a nearby tree). It’s since received a blue paint job and operates as a chiropractic clinic.

Paint job aside, it’s still hard to envision the house in Illinois where the action of the film took place. But as Carr points out, filmmakers love to shoot suburban scenes in Pasadena because of its traditional, craftsman style homes and more importantly, its lack of palm trees.

But the best explanation as to why this home looks so different from the one we see in the film is that the entire house has actually been moved. In 1987, the house was in danger of being demolished. Super-fan David Margrave (with the support of fellow Pasadena residents) bought the home for $1, with the promise to move it somewhere safe. The house landed just a few blocks away, right across from the South Pasadena train station.

The Luggage Room/La Grande Orange Cafe

You may not recognize the former Santa Fe depot from movies or television, but its connection to Hollywood dates back to its golden age. Today, the old train station has been faithfully restored to house two restaurants: the dinner and cocktail spot The Luggage Room, and the daytime, family-oriented La Grande Orange Cafe.

A hub of the Santa Fe railway and home of the Super Chief streamliner, the Santa Fe depot was favored over Union Station by some of cinema’s biggest stars because going incognito in Pasadena was easier than it was in downtown Los Angeles. Additionally, the Super Chief (which could get you to Chicago and Kansas City) was considered the height of luxury in travel and was one of the first trains to serve gourmet food. Diners could treat themselves to a champagne and steak dinner.

The two restaurants have preserved plenty of the original structure’s details. La Grande Orange Cafe’s dining room was the depot’s original waiting room, while the Luggage Room was the partially open-air storage facility where luggage was passed from the train through the station through large windows. A peek into the open-air kitchen reveals the bones of the depot’s old ticket counter.

After three days immersed in film history, end your journey by taking a seat at a former Hollywood hideout. Unlike plenty of the locations included in this itinerary, this is a place that could only be found in Los Angeles.

This post is published in partnership with Discover LA. Click here to discover your LA adventure.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook