How a Food Writer Spends 3 Obscure Days in Los Angeles

Katherine Spiers takes us on an expansive tour of L.A.’s global food influences.

It’s impossible to discuss Los Angeles cuisine without delving into the city’s history of multiculturalism. Waves of immigration from just about every corner of the globe have both defined L.A.’s dining culture and made it nearly impossible to categorize. Understanding food in Los Angeles requires some (delicious) homework.

The city’s culinary trajectory is a vibrant narrative that continues to evolve. More than ever, dishes that combine disparate influences are entering the canon (think: Korean tacos). In other parts of the United States, the term “fusion cuisine” may elicit groans, but in Los Angeles it’s simply a matter of fact. The adult children and grandchildren of immigrants are experimenting with flavors that have been passed onto them, combining them with the tastes they’ve encountered while growing up in one of America’s most diverse cities.

It wasn’t until the writer Katherine Spiers moved to Los Angeles over a decade ago that she became deeply interested in food. She found in the city a place to explore different cultures’ cuisines from angles she’d never even considered before. For example, she says, understanding the differences in a banh mi sandwich from Ho Chi Minh City and one from Hanoi can help form a better understanding of the country’s history and cultural nuances.

A former food editor for LA Weekly, Spiers has spent the past 10 years immersing herself in Los Angeles’ rich multicultural culinary scene. She currently hosts a podcast, Smart Mouth, in which she interviews local notables, always in pursuit of a fuller understanding of gastronomic history.

With the help of Spiers, we’ve assembled a three-day itinerary that highlights some of Los Angeles’ most unusual and exciting food ventures, along with key cultural monuments that contextualize the city’s embrace of immigrants and the foods they bring with them.

Day 1 Agenda:

-

Ride the Angel’s Flight Funicular

-

Take a stroll through Los Angeles history in Grand Central Market

-

Visit El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument

-

Drink and dine at Here’s Looking at You

Angel’s Flight

Start the day (and the journey!) as many Angelenos did at the turn of the century. Just across the street from Grand Central Market is Angel’s Flight, a narrow-gauge funicular built in 1901. In its early years, Angel’s Flight carried wealthy residents of Bunker Hill downtown to their jobs for just a penny a ride.

A plaque at the top of the funicular declares it to be the world’s shortest incorporated railway, traveling a 33-percent grade for 315 feet. The same signage estimates that Angel’s Flight has carried more passengers per mile than any other railway in the world: 100 million in its first 50 years.

But by the 1960s, Bunker Hill’s demographics had changed, as its well-to-do denizens moved to the suburbs. Angel’s Flight ceased operation in 1969, and the neighborhood was eventually razed as part of a controversial redevelopment project. A sleek, elevated complex of skyscrapers took its place.

The conveyance reopened two blocks away in 1996, and as of August 2017, Angel’s Flight is open for business. At $1 per ride, it’s worth a roundtrip to experience the unique commute of many turn-of-the-century Angelenos.

Grand Central Market

Grand Central Market was made to last. When it opened in 1917, it occupied Los Angeles’ first ever steel-enforced, fireproof structure. Located just steps away from Angel’s Flight, its vendors originally catered to Bunker Hill’s wealthy residents (Los Angeles magazine once described it as a “Jazz Age version of Whole Foods.”)

As Los Angeles grew more diverse post-World War I, so did the purveyors and shoppers at Grand Central Market. Immigrants from all over the world were introducing Angelenos to brand new types of Mexican, Jewish, and Japanese cuisines, to name only a portion.

In the middle of the century, like many downtown locations, the market experienced economic decline. The profile of the average shopper changed, but the market never ceased to attract customers. During this period in particular, Grand Central Market was lauded for the diversity of its vendors.

The market began its transformation into its current incarnation in 1985, when the attorney Ira Yellin and his wife Adele bought the property with the plan to reinvent it as a dining destination that would beckon people back downtown. But the venture was ill-timed.

It wasn’t until 2011, when residents began flocking back downtown in droves, that Adele, who carried on the project following the death of her husband in 2002, was able to restore the market fully to its former prestige.

As Spiers explains, the evolution of Grand Central Market has always mirrored the development of Los Angeles itself. For years, rents remained low and hospitable to immigrants in downtown Los Angeles. But in recent years, upwardly mobile young people have moved downtown, as they have in many cities across the United States. Once again, Grand Central Market serves a well-to-do set. Yet some of its oldest tenants have found a way to remain (one of the most popular being China Cafe, which has been open continuously for nearly 60 years).

Grand Central Market warrants a visit as a place for examination and reflection on Los Angeles’ ever-evolving landscape. And with world-class vendors including Wexler’s Deli and Sarita’s Pupuseria (another longstanding tenant), you won’t walk away hungry.

El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument

Take a moment to digest by walking over to El Pueblo de Los Angeles Historical Monument, a gathering of landmarks that honor the city’s very first settlers and celebrate waves of immigration since 1781.

Highlights of the monument include the buzzing Mexican marketplace located on Olvera Street, the Chinese American Museum, and the América Tropical Interpretive Center—a viewing platform and visitor’s center displaying the artist David Alfaro Siqueiros’s controversial 1932 mural, América Tropical. When the mural was first unveiled in the 1930s, it met with outcry for its critical depiction of the city’s treatment of Mexican laborers. Within a year of its debut, it was literally whitewashed.

Ironically, the white paint that was intended to erase Siqueiros’ mural ended up protecting it from natural elements that could have destroyed it over time. With the help of Los Angeles’ first Mexican-American mayor in more than a century (Antonio Villaraigosa) and the Getty Conservation Institute, Chicano artists and activists were able to partially restore the mural in 2012.

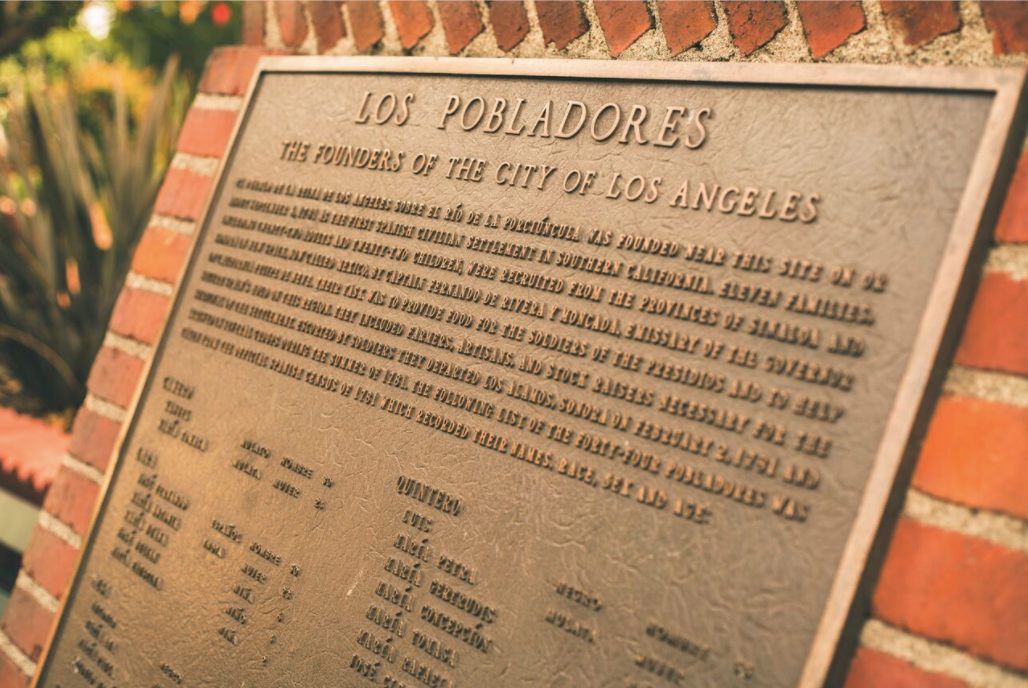

At the very center of the historical monument, a stately gazebo known as Los Angeles Plaza Park may be the most visible structure inside El Pueblo de Los Angeles, but its most poignant feature is easy to miss. A large plaque laid in brick lists, by name, the 44 original settlers of Los Angeles alongside their age, gender, and ethnicity. Archaic terminology notwithstanding (“negro” and “mulatto” are among the ethnic designations) the plaque is a proud testament to the too-often overlooked role that early Angelenos of African descent played in the city’s founding.

Here’s Looking at You

End the day by beginning a tour of Koreatown about seven miles away, in a restaurant that doesn’t serve Korean food. Despite boasting an impressively diverse array of international influences, the menu at Here’s Looking at You shows no loyalty to any particular cuisine, except for Los Angeles’.

The restaurant slyly upends tradition by asking diners to reconsider preconceptions of regional cuisine. Frog legs, for example, are often seen as a staple of French cuisine, but at Here’s Looking at You, they’re tossed in a salsa negra seasoned with five different chilis and spritzed with lime juice. It’s a dish that speaks to this city’s culinary advantages: its ethnic diversity and the availability of fresh produce.

Just as notable as the food are the cocktails. Allan Katz and Danielle Crouch of Caña Rum Bar (which boasts Los Angeles’ largest selection of rums) were consulted to perfect the tiki-inspired bar menu.

Los Angeles’ special relationship with tiki culture can be traced back to a single person: Ernest Gantt, a.k.a. “Don the Beachcomber.” A former bootlegger born in Texas, he moved to Hollywood in the 1930s and opened the city’s first-ever tiki bar, called Don’s Beachcomber. The kitschy, Polynesian environs and fruity rum cocktails proved to be popular with a celebrity clientele, but it wasn’t until after World War II that tiki culture truly exploded. Veterans (including Don himself) returned home from war with stories, captivating the country with a newfound interest in Pacific culture.

Though the bar menu changes seasonally, it’s clearly dedicated to preserving and advancing Los Angeles’ relationship with tiki culture. You’ll find some surprising ingredients on the bar’s menu, but the cocktails at Here’s Looking at You seem less interested in experimentation than the food. It appears that some things are sacred to Angelenos, tiki drinks being one of them.

Day 2 Agenda:

-

Try the eponymous meat at Sahag’s Basturma

-

Visit Barnsdall Art Park

-

Eat a cheeseburger in Chinatown

-

Stay out until the early morning hours at Dan Sung Sa

Sahag’s Basturma

Begin the day just north of Koreatown in Little Armenia. “Try basturma, the ancient predecessor to L.A.’s beloved pastrami, and tuck into a full breakfast,” says Spiers. Pastrami may not be the most popular breakfast choice, but it’s not unheard of. With this in mind, it doesn’t seem so unusual that Sahag’s Basturma opens at 8 a.m.

The process of salting, seasoning, and air-drying beef dates back to the Byzantine era. Armenians originated the technique and came to be known as the masters of its creation. Families that processed basturma were known by the proper name of “Basturmajian.”The Armenian tradition lives on at Sahag’s Basturma, an unassuming deli and grocer nestled in a strip mall.

Since 1987, the establishment has served its signature basturma in addition to a variety of deli items, including soujouk (Armenian sausage) and maaneg (Lebanese veal sausage), as well as spices, preservatives, and sweets from the Middle East. Unsurprisingly, its most popular menu item is the basturma, which you can buy by the pound or in a compact sandwich served alongside shriveled black olives, peperoncinis, and pickled radishes.

The sandwich may look puny, but one bite in and you’ll realize why Sahag’s exercises caution in its portions. Even tempered by slightly sweet, pressed french bread and cold tomatoes, its savory flavor is nearly overwhelming. Eat at one of the deli’s two tables, or take your sandwich on the go to picnic at the next stop.

Barnsdall Art Park

Less than a mile from Sahag’s Basturma, the Hollyhock House is perennially perched on a hilltop above Los Feliz, now part of a larger complex known as the Barnsdall Art Park. Maintained by a nonprofit, the organization is dedicated to community engagement in the arts, managing a low-cost theater space, free art classes, and a museum devoted to exhibiting Southern California artists of diverse backgrounds.

The park dates back to 1919, when the oil heiress Aline Barnsdall bought 36 acres of land with the intention of creating a commune for artists and free thinkers. A radical feminist and champion of progressive causes, she enlisted her friend, Frank Lloyd Wright, to build the house. Wright designed the home in a style that combined Mayan and Japanese influences, predating his equally famous (and visually similar) Ennis House.

Barnsdall was difficult to please, and her correspondence with Wright during the time of the house’s construction reveals the erosion of their friendship. She complained of a leaky roof, heavy doors, and small rooms. After firing Wright in 1921, she gave up her vision for an artists’ utopia overlooking Los Feliz and eventually donated the land to the city of Los Angeles.

Her loss was ultimately the city’s gain. Looked upon generously, one could even say that her dream has finally been realized.

Burgerlords

Head back down south for a California cheeseburger specialty in an unlikely place: Chinatown’s Central Plaza.

Brothers Frederick and Maximilian Guerrero (along with business partner Kevin Hockin) opened Burgerlords in 2015, having spent the previous decade helping launch their father Andre Guerrero’s popular restaurant, The Oinkster. Famous for its pastrami, pulled pork, and burgers, one menu item stands out: the ube milkshake. A Filipino dessert made from purple yams sweetened with sugar and coconut milk, it’s the only item on the menu that suggests the family’s Filipino heritage.

Growing up in northeast Los Angeles, Chinatown was a dining destination for the Guerrero family. Frederick and Maximillian chose Chinatown’s Central Plaza because of their shared, nostalgic affection for the place in addition to what they saw as a dearth of fast food restaurants in the area.

Compared to The Oinkster’s decadent menu, Burgerlords’ options are modest, as is the size of their cheeseburgers. They’re a well-done rendition of Los Angeles’ signature, thousand-island dressed, one-handed sandwich. Aside from their exceptional quality, the only thing unusual about the cheeseburgers is that their creators have never tried them. The Guerreros are both vegetarians.

Hence, the vegan option is a patty made of roasted eggplant, garbanzo beans, barley, leeks, celery, and a special spice mix. Vegetarians will tell you that this is one of the best renditions of a notoriously hard-to-pull-off culinary challenge.

Take a moment to explore Central Plaza’s colorful, albeit Disney-fied rendition of Chinatown. A seven-foot statue of Bruce Lee strikes a pose just steps away from Burgerlords. Also next door: the respected art shop, zine publisher, clothing store and event space Ooga Booga, located on the second floor of a multi-use building.

Dan Sung Sa

You may want to take a rest before heading back to Koreatown’s Dan Sung Sa, where it’s easy to lose track of time and make a late night of it. “Dan Sung Sa is one of the greats, even though it’s not the KBBQ the whole city is so obsessed with,” Spiers once wrote in a review.

The first thing one notices upon arriving at Dan Sung Sa is a mural that towers over its entrance featuring four figures, only one of whom is instantly recognizable: Kim Jong-Il. Owner Carol Cho is quick to dispel any rumors that the restaurant has friendly ties with North Korea. The mural, she explains, depicts a a civil interaction between Kim Jong-Il and beloved former South Korean President Kim Dae-Jung. The only Korean Nobel Prize winner in history, Dae-Jung was praised for his efforts at ameliorating tensions with North Korea.

The second thing one notices upon entering is how dark Dang Sung Sa is. “Do you like drinking under the light?” Cho asks rhetorically. “We don’t.” Virtually windowless, the interior is encased in brick and dark wood. The kitchen is open until 2 a.m., making the spot a popular destination for homesick expats, rowdy drinkers, and everyone with a curious palate in between.

The large menu features meat and vegetable skewers, traditional Korean dishes, and a curious selection of items born from the melding of Korean and American culture.

In the 1950s, Los Angeles experienced its second major wave of Korean immigration following the Korean War. Adapting to their environs, Koreans incorporated American staples into their diet. Packaged goods arriving from the West after the war, in turn, influenced Korean cuisine back home. Dan Sung Sa serves corn cheese (creamed corn topped with cheese), french fries, and a grilled sliced spam and egg fry.

Dan Sung Sa aims to be a place that feels like home for Korean expats. It’s open 365 days a year, adhering to an altruistic policy that values camaraderie above all else. For immigrants, a creeping feeling of displacement arises during the holidays. The spot aims to be a home away from home during these times of the year, because, as Cho puts it, “those are the days when you need it the most.”

Day 3 Agenda:

-

Detox at Natura Spa

-

Cool down with a cold dessert at Saffron & Rose Ice Cream

-

Treat yourself at Shunji Japanese Cuisine

-

Make a pilgrimage to Randy’s Donuts

Natura Spa

If you went overboard on the soju at Dan Sung Sa, begin your last day in Los Angeles detoxing at one of Koreatown’s famous spas. But with so many options to choose from, which should you visit?

Natura Spa may not be the most well-known spa in Koreatown, but it’s definitely the most unusual. In addition to offering all the facilities (saunas, swimming pools) and services (massages, body scrubs) you would expect, it also gives customers the unique opportunity to soak in watery bliss beneath the remains of an abandoned luxury department store.

Built in 1939 by the architect Myron Hunt (who also designed the monumental Ambassador Hotel), the Wilshire Boulevard branch of the luxury department store I. Magnin was described at its opening as a “symphony of beauty.”

Closed in 1990 and re-opened in 1992 as the “Korean-oriented” Wilshire Galleria, it’s evident that aside from Natura Spa, the massive structure hasn’t seen much development since the closing of I. Magnin. Entirely closed to the public save for Natura Spa, one can sneak a peek at the department store’s interior by peering through the galleria’s locked entrance on Wilshire Boulevard.

Natura Spa’s entrance is located around the corner, where a former parking circle once chauffeured clients straight through the department store’s doors. Entering now, one encounters two entrances: male and female. The male entrance is, ostensibly, at the end of what appears to be a maze of plywood. To the left is a more a direct, polished entrance for women. An elevator ushers visitors to an underground oasis.

Saffron & Rose

You’ll have to head back west to the airport eventually, and if you’re still feeling steamy from the spa, make a pit stop at Saffron & Rose.

“We have really good ice cream [in Los Angeles],” Spiers says, “because we have cows and fruit in the state.” Indeed, Angelenos are spoiled with options when it comes to ice cream. For those who haven’t tried it, Spiers recommends the Persian variety served at Saffron & Rose, located on a stretch of Westwood Boulevard colloquially known as “Little Tehran.” “They do use a lot of Persian and Middle Eastern flavors that we are less likely to see in ice cream here,” she says.

Persian ice cream utilizes powdered salep (ground orchid root) and whole milk, giving it a thicker, more viscous consistency than traditional ice cream or gelato. The shop’s best seller combines pistachio with saffron’s subtle floral notes and feels both familiar and transportive. For the less adventurous, it’s a delicious introduction to Persian ice cream.

The menu focuses heavily on fruits (dates, pomegranates, and guava, to name a few) and rosewater, but there are also purely American creations including cookies and cream. The shop also serves faloodeh, a popular Iranian frozen dessert made of vermicelli noodles and rose water.

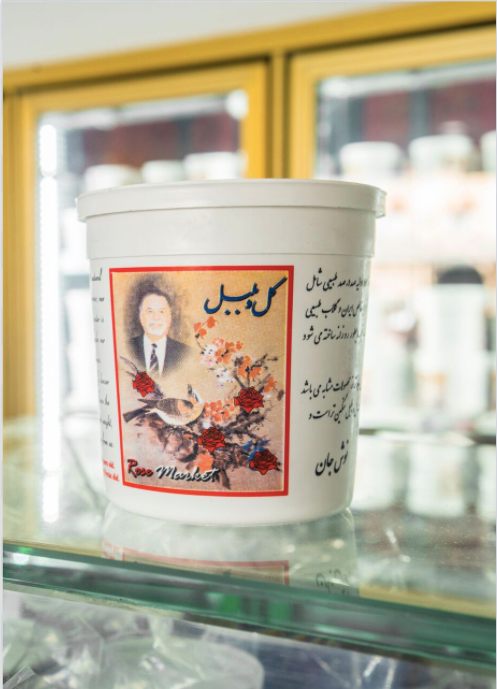

Pints of ice cream line the back wall of the shop, featuring an illustration of Saffron & Rose’s original owner, Haji Ali Kashani-Rafye, who began selling ice cream when he immigrated to Los Angeles from Iran in the 1970s. After his death, his two children and grandson took over. His legacy is palpable in the ice cream shop, and within the many nearby establishments that sell pints of ice cream labeled with his countenance.

Shunji Japanese Cuisine

“L.A. was the first place in America that had sushi restaurants,” Spiers notes. In 1966, the Japanese businessman Noritoshi Kanai opened a nigiri sushi bar inside a Japanese restaurant called Kawafuku. For your last meal in Los Angeles, treat yourself to a luxurious sushi dinner in a not-so-luxurious location.

Los Angeles Times food critic Jonathan Gold once wrote of Shunji Japanese Cuisine: “Some of the best Japanese restaurants in Los Angeles have always occupied some of its grungiest real estate.” Noting that the bathrooms are located outside of a restaurant owned by a renowned chef, where an omakase dinner can cost upwards of $120, Spiers echoes the sentiment: “We keep it humble.”

What Shunji Japanese Cuisine’s exterior lacks in glamour, it makes up for in charm. It’s impossible not to stifle a giggle pulling in to the oddly shaped structure. Once the home of a now-extinct barbecue franchise, the building was erected to resemble a chili bowl at the height of southern California’s obsession with programmatic architecture in the 1930s.

Despite being known for its sushi, the restaurant’s most noteworthy dish doesn’t involve fish at all. Chef Shunji Nakao is the inventor of agedashi tomato tofu. It’s a dish made from dissecting a tomato and condensing it into a square with a tofu-like consistency, topped with a splash of dashi (the same broth used at the base of miso soup).

Nakao’s establishment is just as notable for its vegetable dishes as it is its fish, and the tomato tofu is representative of Nakao’s approach to Japanese cuisine. He treats common vegetables with the same care and delicacy as a fine cut of fish.

Randy’s Donuts

You can’t leave Los Angeles without stopping by Randy’s Donuts. Fortunately, it’s located close to LAX, and no matter what time your flight takes off, Randy’s will be open.

By the 1950s, programmatic architecture in Los Angeles had shifted from the buildings themselves to their signage. Car culture was beginning to truly reshape the city, and roadside drive-ins scrambled to capture drivers’ attentions. Oftentimes, signs could be easier to read and discern than buildings themselves.

Though the gargantuan doughnut that tops Randy’s Donuts is technically a sign, it dwarfs the eatery below it, effectively straddling both iterations of programmatic architecture. It’s safe to say that in competing for motorists’ interest, Randy’s Donuts steamrolled the competition.

But Randy’s Donuts hasn’t just abided for all of these years because of its quirky appearance. You can still buy a doughnut there for a handful of change, and they’re simply, plainly delicious. Add to that that they’re open 24 hours, and you’ve got yourself the perfect way to end a culinary adventure in L.A.

This post is published in partnership with Discover LA. Click here to discover your LA adventure.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook