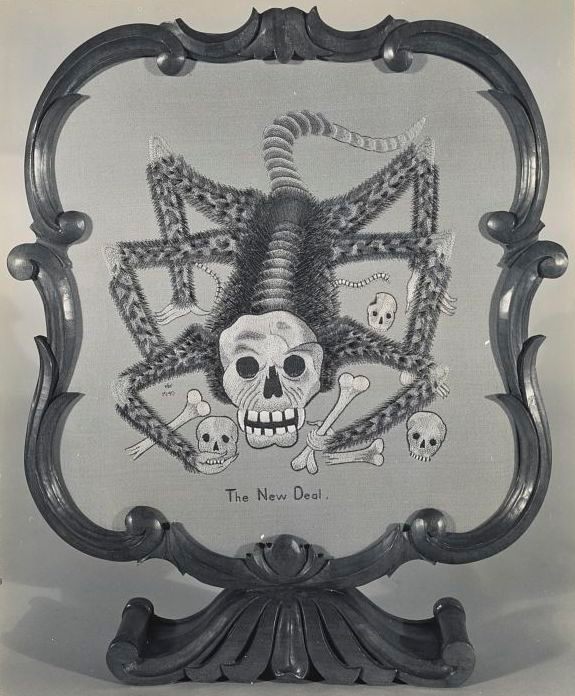

How Better to Protest Federal Policy Than With an Embroidered Scorpion Demon?

Eleanor B. Roosevelt—no, not THAT Eleanor Roosevelt—thought the New Deal was monstrous.

If you want to register dissatisfaction with a piece of legislation, you’ve got a few options. You can contact your local representative. You can join a protest or campaign. Or—if you want—you can embroider a frightening creature onto a piece of satin, and stitch the name of said legislation underneath it, as above.

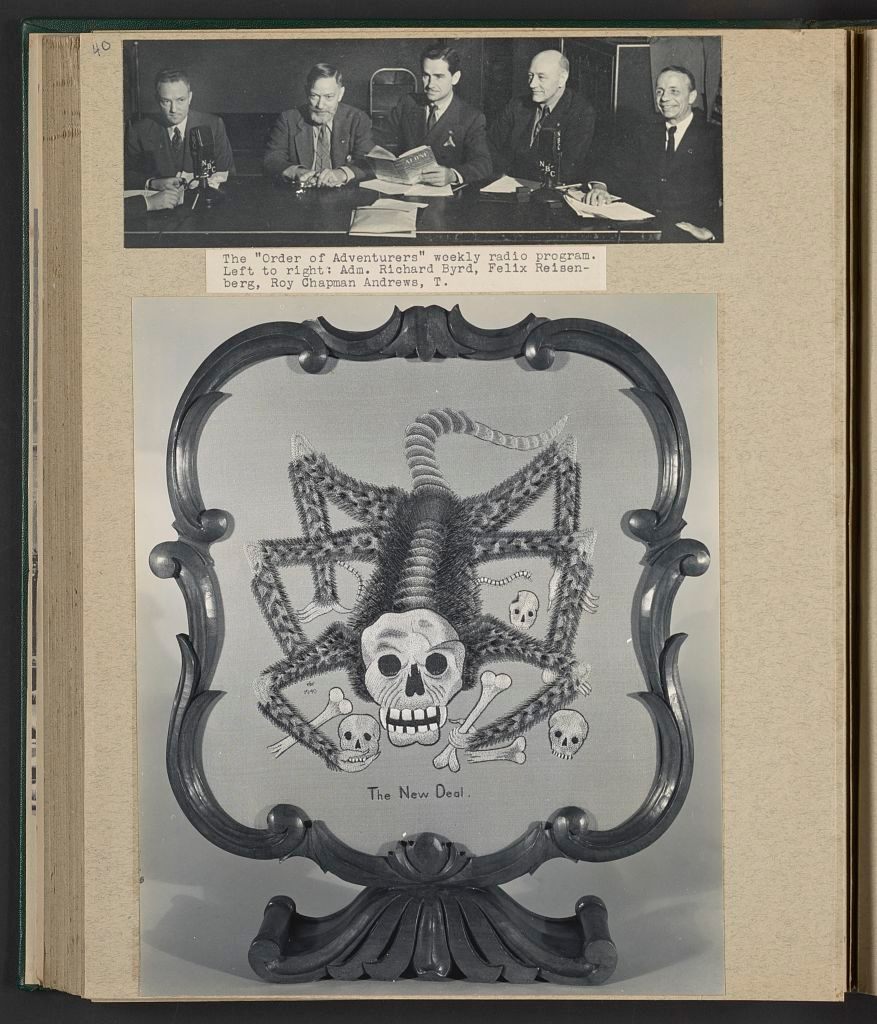

This embroidery, which is based on a work usually credited to the Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada, was made by Eleanor B. Roosevelt.* (She is not to be confused with the other, more famous Eleanor Roosevelt, who probably would have represented the New Deal in a very different way.) Eleanor B. was married to Theodore “Ted” Roosevelt, Jr., the oldest son of President Theodore Roosevelt. Both Eleanor and Ted were staunch Republicans: When Ted’s fifth cousin, Democrat Franklin D. Roosevelt, won the Presidency in 1932, Ted resigned his seat as ambassador to the Philippines. When reporter Inez Robb wrote up the embroidery in 1940, she described the couple as “out-of-season Roosevelts.”

Eleanor began the embroidery at the 1940 Republican National Convention, and finished it three months later, in the lead-up to the election. At the time, FDR was running for his third term against Republican challenger Wendell L. Willkie. The needlework was meant to act like a more traditional political cartoon, portraying the progressive legislation as a hideous monster, “in the theory that a stitch in time may sew up the election for… Willkie,” Robb wrote in the International News Service.

“It’s the most horrible and gruesome thing I could devise,” Eleanor told Robb. “The evil in it is very subtle.” Subtle may not be the right word for the piece, which apparently was sewn with bright red and gray threads into pale blue satin, and features no fewer than four separate skulls, one of which appears to have had a bite taken out of it.

Though Eleanor mentioned having “devised” the creature, her needlework is a clear copy of a 1910 artwork titled “La Calavera Huertista” (“The Huertista Skeleton”). This relief engraving is the creation of either Posada or one of his contemporaries, Manuel Manilla.*

It’s unclear exactly what species it is supposed to be: the Library of Congress calls it “a hairy scorpion with the head of a skull,” while Robb preferred “a body one-part lizard and two parts hairy spider.” (She eventually threw up her hands, describing it as “a dandy little entomological misfit… right out of a Welsh rarebit nightmare.”)

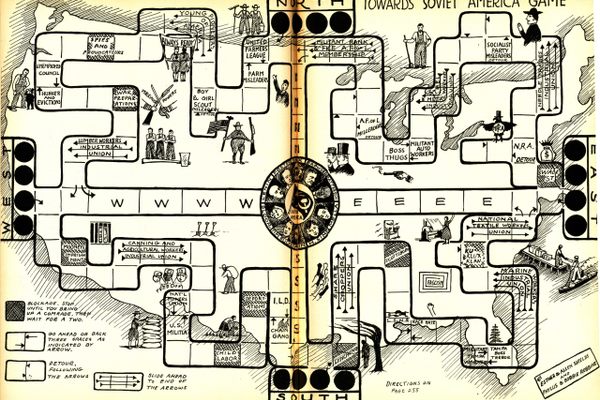

It’s also unclear precisely what Eleanor found evil about the New Deal—the series of federal programs, projects, and stimuli that FDR introduced in 1933 to combat the Great Depression. But if she was on the same page as other Republicans, she probably considered it to be an overreach that didn’t work. Willkie got the party nomination by making arguments along these lines, telling the New York Times that “government monopolies… need [a] licking if the people’s liberties are to be preserved,” and that, by increasing federal debt, the policy “puts this country on a highway which will come to… a smashup.”

The creature’s hodgepodge nature befits its stitcher. As curator Beverly Brannan details at the Library of Congress, even when she wasn’t creating skillful, politically cutting pieces of needlework, Eleanor was a real Jackie-of-all-trades. She was, at various times, the president of the Girl Scout Council of Greater New York, the head of a YMCA canteen in Paris, and a member of the editorial advisory board for Whiz Comics.

She published articles about her home life, and took thousands of photos, which she kept in meticulously ordered scrapbooks, along with relevant newspaper clippings and letters. She also often went with Ted when he was stationed overseas—when he was governor of Puerto Rico, Eleanor was instrumental in securing a living wage for female needleworkers on the island, Brannan writes.

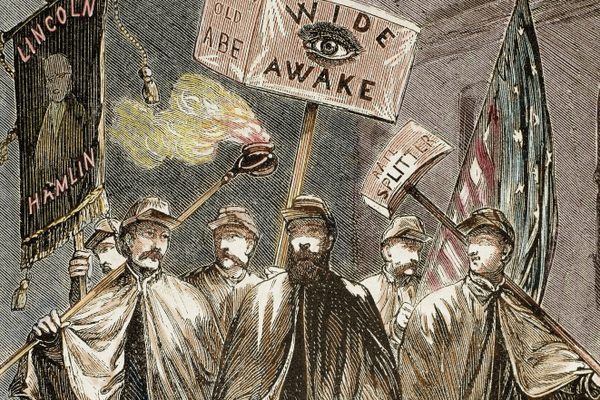

By the time she sewed her New Deal monster, she was familiar with political campaigning, too. When Ted ran for New York State Assembly in 1921, Brannan writes, Eleanor “breached the taboo against women speaking in public and gave stump speeches for her husband.” Stumping led to stunting: In September of 1921, she participated in a mule race against the wife of another local politician, Anne Webb. “It was the most exciting mule race ever seen on the course,” a New York Tribune reporter declared. (The race was a tie, and Roosevelt won his seat.)

Her frightening needlework was less effective: FDR, of course, went on to win his third term, earning 449 electoral college votes to Willkie’s 82. There’s no evidence that Eleanor tried quite the demon needlepoint strategy again, although she continued to create high-quality pieces of embroidery that were featured in various magazines. The scorpion creature stayed hung up in the family drawing room—“in a dark corner,” Eleanor B. explained to Robb. “I wouldn’t want to frighten timid guests.”

*Update: Information on the original Huertista Skeleton artwork came to us post-publication—we’re in the process of updating the story to include more details on it, José Guadalupe Posada, and Manuel Manilla.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook