New York City’s Mail Chutes Are Lovely, Ingenious, and Almost Entirely Ignored

Glorious example at the exquisite Fred French building. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

If you have ever worked in an old building, the chances are you will have at some point walked past a small mysterious brass box . Located about halfway up the wall, it is notable for a flat length of glass leading both into and out it, disappearing into the ceiling and the floor below. Often painted over, ignored and unused, they are a relic of the golden age of early skyscrapers called the Cutler mail chute.

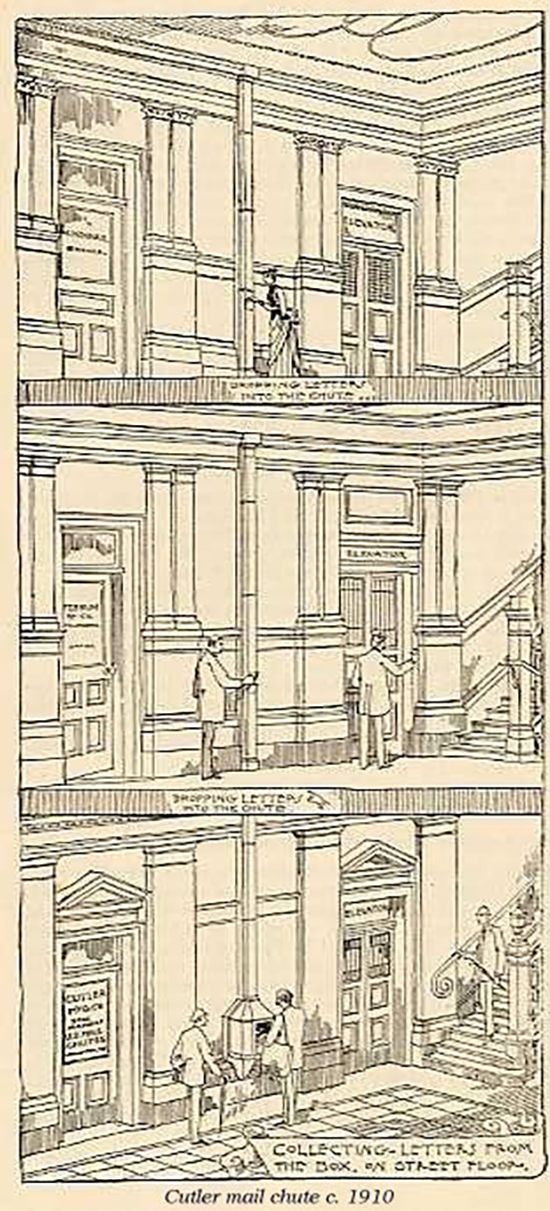

The Cutler mail chutes flourished during the advent of the first multi-story buildings in the turn of the 20th century. The invention was fairly simple: the glass chutes would run internally the length of the building, with a mailing slot on each floor. Rather than having to make the trek downstairs to find the nearest mail box or post office, you would simply pop your letter into the chute from whichever floored you worked on, and gravity would swiftly carry your letter to a mailbox in the lobby, for daily collection from the postman. In an era when people were sending handfuls of letters each day, the convenience of the Cutler mail chute was a godsend.

Most Cutler mail chutes were installed along side elevator cars. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Remarkably today, the Cutler mail chute is still in use. In fact there are approximately 900 actively working in New York and just over 360 in Chicago alone, from which the post office still routinely collects the mail.

The mail chute was invented by James Goold Cutler in Rochester, NY, in 1883 and was first installed at the Elwood building in the center of the city. It proved an instant success and Cutler received the patent for the mailing system, that secured him a virtual monopoly for the next 20 years.

The patent specified that the lobby box itself must be made “of metal, distinctly marked ‘US Letter Box’”, and that the “door must open on hinges on one side, with the bottom of the door not less than 2’6 above the floor.” To protect items of mail that would be dropping from many floors, Cutler outfitted the lobby box with an “elastic cushion to prevent injury to the mail.”

Sketch of a mail chute in 1910. (Photo: Public Domain/WikiCommons)

Working in close co-operation with the post office, Cutler’s patent system was first installed in railways and public buildings.

But as cities boomed skywards, over the next 20 years Cutler sold over 1,600 mail chutes, making their way into brand new, state of the art skyscrapers, office buildings, apartments and hotels. In their exemplary illustrated design history called Art Deco Mailboxes, writers and mail chute aficionados Karen Greene and Lynne Lavelle, note how Cutler’s system quickly became as “essential to the operation of any major hotel, office, civic or residential building as the front door.” And according to report from Rochester in 1888:

“In the present age of multi-storied buildings, no builder or owner of such an edifice has all the needful and convenient appliances until the Cutler US Mail Chute is in use therein—a device as necessary for the businessman as the elevator.”

The mail chute system might have born out of functionality, but Cutler infused the mailboxes themselves with elegance. His catalogue offered lobby boxes furnished with gleaming brass fittings and elaborate detailing. He also had the foresight to collaborate with the leading architects of the day to allow the design of individual mail boxes that would match the grandeur of specific buildings. Through the Beaux Arts movement to Art Nouveau to Art Deco, Cutler’s mailboxes became increasingly beautiful and ornate. The Cutler Co. worked with architects such as Daniel Burnham (the Flatiron), Shreve, Lamb & Harmon (the Empire State), Sloan & Robertson (the St.Regis) and Cass Gilbert (the Woolworth).

Manufactured, designed and first tested in Rochester, NY, Cutler mail chutes were an indispensable feature of early skyscrapers. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Cutler held the patent for the mail chute giving him a virtual monopoly for decades. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The St. Regis still operates one of the most luxurious lobby box, decorated with the Federal Eagle motif. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

As letters grew in size, clogging of the mail chutes became an increasing problem. A famous example occurred at the grand old McGraw Hill building on West 42nd Street. Once an emerald Art Deco masterpiece, and former home of Marvel Comics, the building has now faded into disrepair and a clog in their mail chute was discovered in the mid 1980s. When it was eventually tracked down and cleared, the resulting avalanche of undelivered mail filled 23 sacks.

Occasionally, letters get stuck for much longer than that. In 1995, in Brooksville, Florida a lady called Marguerite Grisdale Lynch was astonished to receive a letter from her husband 50 years after he dropped it in a mail chute in a Michigan Veteran’s hospital. He had already been dead for 19 years.

By the 1990s, fire codes all but outlawed Cutler mail chutes from being installed in new buildings. Bespoke mail rooms replaced their use. And some of the ones still in operation are gradually on the wane; the Chrysler building recently sealed theirs, whilst the glitzy Waldorf-Astoria also closed their three chutes.

The buildings that house the chutes today are a varied lot. Some are grand, such as the gleaming gold lobby of the Fred French, the sleek chromium and steel of the Chrysler, the sophistication of the Roosevelt hotel, and the magnificence of Grand Central Station. Others are more functional like the Port Authority bus terminal, and countless offices lining Broadway, the Garment District and Fifth Avenue.

One of the standard Cutler mail chute boxes at the author’s place of work, West 34th Street. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The chute that is still in use at the Roosevelt hotel. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

Cutler mail chutes were to be found in some of New York’s most famous locations: here, Grand Central Station. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

From left: Cutler worked with famous architects to customize lobby boxes for different buildings, such as this at One, Grand Central Place; Art Deco styling at the Empire State Building, and still in operation; and Lobby of the Algonquin Hotel, perhaps used by Dorothy Parker and the Vicious Circle. (Photo: Luke Spencer)

The first Cutler mail chute I noticed was in my own work building, a fairly average 20 floor office built in 1927 on the corner of 10th Avenue and 34th Street. The chute on my floor, the 5th, had long been painted over in white, but the slot was still open. The mailbox in the lobby didn’t display any of the art deco flourishes of, say, the Cutler box in the old Western Union building. but was still neatly furnished with the brass fittings and black painted inlays of the standard Cutler model 4165. Speaking to the lobby security guard, he didn’t recommend using it up past floor 16 as there was a blockage somewhere. “Sometimes the super will go up and drop something heavy down there to clear it,” he said.

Every day, though, the postman still retrieves letters from the lobby box at the end of the Cutler chute.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook