Peek Inside Buffalo’s Abandoned Art Deco Train Terminal

A look at the empty grand hall of a once-bustling station.

The main Amtrak stop in Buffalo, New York is known informally as ‘America’s Saddest Train Station’. A modest, one-story brick building, smaller than the average house, it currently sits with a blue tarpaulin covering its roof, which partially collapsed during a storm in September 2016. It’s a symbol for the struggles and hardships, most of them economic, Buffalo has faced in recent history.

But a little further east is another train station, lying forlorn and mostly forgotten. It also happens to be one of America’s Art Deco treasures: the old Buffalo Central Terminal.

Opened in 1929 for the New York Central Railroad, the Buffalo Central Terminal was every bit as grand and opulent as Manhattan’s Grand Central Terminal, Philadelphia’s 30th Street station and Washington DC’s Union Station.

These were the days when Buffalo was known as the Queen City, built on the strength of automobiles, livestock, steel, and other heavy industries prospering along the seam of the Erie Canal, connecting New York to the Great Lakes. Buffalo thrived to such an extent it was chosen to host the prestigious 1901 Pan American World’s Fair. At this point, Buffalo was the eighth-largest city in the United States.

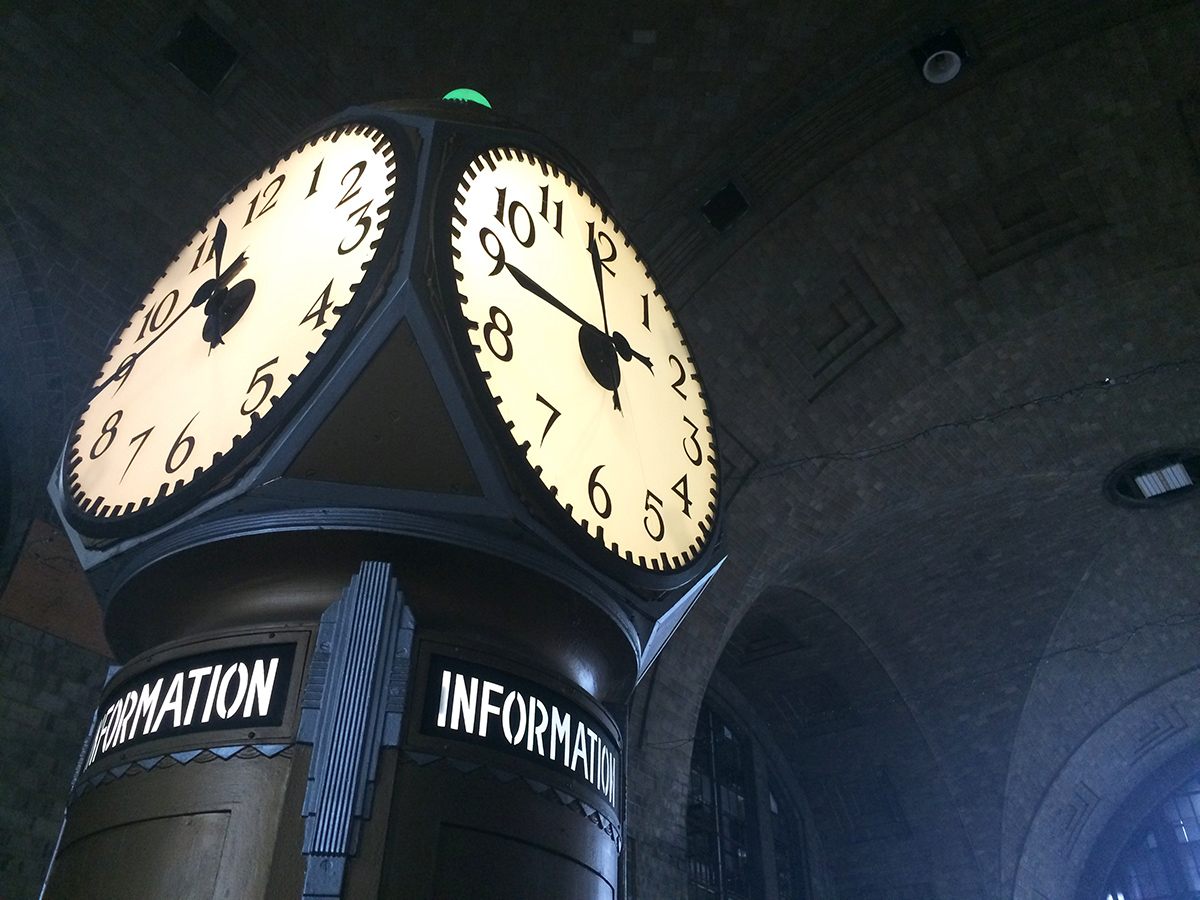

Designed in stunning Art Deco style by Alfred T. Fellheimer, the principal architect of New York’s Grand Central Terminal, it featured an ornate dining room, telegraph offices, luncheon rooms, soda fountains and liquor stores. It even had its own in-station tailors. Towering over the Terminal was a 17-story, state-of-the-art office complex for the New York Central Railroad. This was the golden era of refined, luxurious train travel; of sleeper cars, red caps, and the romantic sounding lines like the 20th Century Limited, the Chicagoan, the Empire State Express and the Knickerbocker. In its heyday, Buffalo Central Terminal was servicing 200 trains a day.

But the decline in Buffalo’s economic fortunes, and the rise of domestic airlines and automobiles, spelled the end of the grand Terminal. In the early hours of the morning of October 28, 1979, the last Lake Shore Limited train service heading west left Buffalo. The grand old Terminal was never used again.

For decades, the building was left abandoned, silently falling apart, while the surrounding neighborhood similarly declined. But the spirit of the Nickel City is strong. No more so than in the recent efforts of the non-profit, Central Terminal Restoration Corporation (CTRC), which has been fighting to not only preserve the Terminal, but restore it to its original magnificence.

The cavernous, ornate ceilings are cathedral-like in size, and echo with the sounds of footsteps on the marble and concrete floors. Stenciled lettering above empty doorways shows where there were once newspaper stands, ticketing offices and deluxe services for the luxurious Pullmans.

Adjacent to the shoe shine kiosks is a long private room, that like most of the Terminal has been all but stripped of anything that could be sold. But the faded markings on the floor show the imprint of curved U-shaped dining counters. It is easy to imagine a din in the building and the excitement of passengers waiting for the grand cross country trains, or newlyweds heading to Niagara Falls, or the tens of thousands of GIs who passed through here on the way to Europe.

One of the largest problems facing the Terminal is in keeping the elements out. Carl Skompinski, a Buffalo resident who has been working with the non-profit group that has owned the Terminal since 1997, says that once they found kids had broken in and were ice skating across the Terminal floor.

“I got involved because I grew up in the area,” Skompinski explains. “I’d like to see it reopening as a multi-use facility with offices, condos or apartments in the tower, a publicly opened concourse and Amtrak station. I’d like it to be a gathering place for the community and be able to be self-funding.”

With the current Amtrak station downtown in such a state of disrepair, there have been calls in Buffalo for a new station. Skompinski and his group argue that there’s no need to build a new one when the beautiful Central Terminal is ready to be used. “The main line runs past the Terminal already,” says Skompinski. All Amtrak would have to do “is run a couple pair of tracks to the old platform building.”

But the building itself would need extensive repairs. Forty years of neglect have seen much of the original fixtures either stolen or stripped, particularly in the mid 1980s, when the Terminal was sold off in a foreclosure sale. One ornate Art Deco lamp found its way into a Hong Kong nightclub. Today, the CTRC maintains excellent security, preserving what is left, and gradually refitting the Terminal. But the process is expensive and a labor of love; each glass bulb for the ornate outside fixtures costs $220, and there are over 20 to replace.

While Buffalo doesn’t attract the numbers of tourists of other major East Coast cities, it is a city rich in history and architectural treasures—none more so than the forgotten beauty of the old Central Terminal.

Perhaps the best chance for the Terminal’s rejuvenation lies with Canadian property developer Harry Stinson, who was named as the designated developer of the site by the City of Buffalo and the CTRC in 2016. Plans include a hotel, offices, stores, restaurants, housing and entertainment spaces. Whether the trains return to the station is yet to be determined.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook