Why the U.S. Government Treats Catfish Unlike Any Other Fish

There’s a strange political battle over how catfish should be regulated.

In early December, the House Freedom Caucus—a group of conservative Republicans aiming to push their party rightward—released a detailed agenda for the first 100 days of the new administration. The document consists mostly of hundreds of existing rules they’d like to see repealed. Some are expected targets: climate regulations, Title IX provisions, the National School Lunch Program. Others are a bit more surprising—they also want to roll back conservation standards for ovens and dishwashers, and block rules that would restrict tanning to consumers over 18.

But high up at the top, in box 3A, flops an unusually slimy legislative actor: the catfish.

An unexpected political hot potato, the regulatory status of catfish has beleaguered Democrats and Republicans alike for nearly a decade. The story of its rise to controversy involves multiple nations and years of legislative strife—and, perhaps, a rare opportunity for bipartisan consensus.

Catfish has long been an important part of the American diet. Native Americans and European settlers stewed and fried them by the millions, and the first large-scale aquaculture endeavors in America were catfish farms, which began stretching across Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi and Louisiana in the 1960s. A few decades later, though, a competitor emerged: pangasius, or “Asian catfish.” A major export of Vietnam, pangasius began swimming into American markets after the U.S.-Vietnam trade embargo was lifted in the mid-1990s, and quickly gobbled up a large percentage of the market.

This has sparked what is known as the “Catfish Dispute”—an ongoing argument between American and Vietnamese producers. Catfish Farmers of America, the industry’s main U.S. trade association, has sued the Department of Commerce repeatedly. Although they have won some victories—all Vietnamese catfish must now be labeled “Made in Vietnam,” for example—it hasn’t been enough to stop the torrent of competition. And so in 2008, they took an unusual step: they asked to be more strictly regulated.

Their argument, at the time, was food safety. “There were a lot of Youtube videos [of Vietnamese fish farms] floating around that were not appealing—it’s not a situation that you want to have your food come from,” says Dan Flynn of Food Safety News, who has reported on this saga since the outset. Together with a few food safety groups, Catfish Farmers of America pushed for more stringent inspections. Thanks mostly to the influence of Mississippi Senator Thad Cochran, the 2008 Farm Bill contained a special provision moving catfish inspection duties from the FDA to the USDA.

Up until this bill, food inspection responsibilities in the U.S. were clearly delineated: the USDA checked out meat, poultry, and eggs exclusively, while the FDA took care of everything else, including our favorite whiskery fish. “This goes back to the days of Upton Sinclair,” says Flynn, “based on the principle that meat should be subject to continuous inspection.”

While the FDA does random inspections, the USDA checks all the domestically produced and imported goods under their jurisdiction, unless they are confident that the countries and states producing the goods have similar inspection standards.

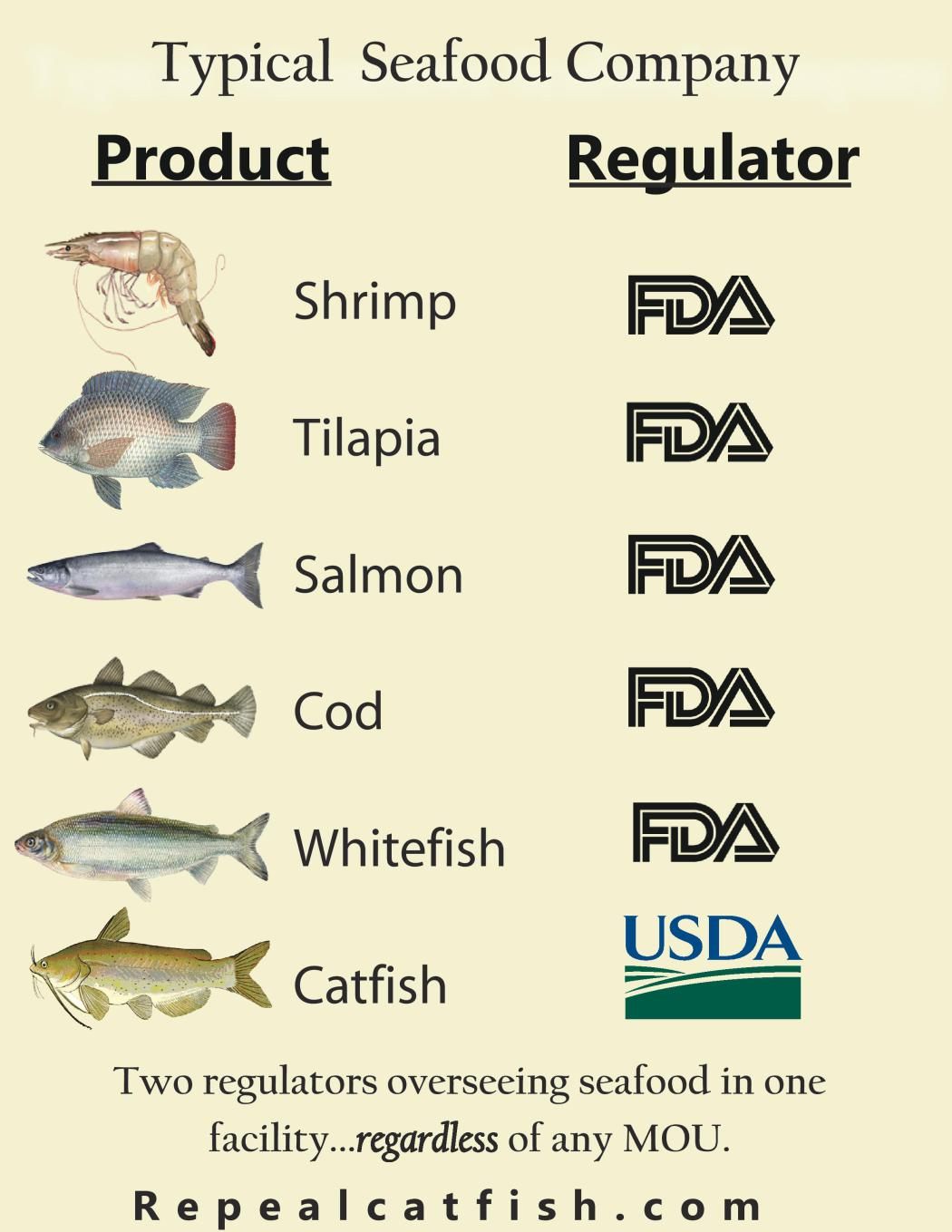

Deciding to treat catfish—and only catfish—like beef or chicken throws a wrench in the system. “When you walk into a facility that processes seafood, you see cod coming down the line, you see shrimp coming down the line, or tuna. All of those products are regulated by the FDA,” says Gavin Gibbons of the National Fisheries Institute, a U.S. seafood industry trade group. “Now stop the presses—quite literally!—refit the manufacturing, and roll the assembly line again for catfish, and now USDA is the regulator.”

It is—and here Gibbons uses that bogey-word that sinks so much legislation—duplicative: “We do not need the police department and the sheriff standing at the stop sign to make sure people don’t run it.”

So far, though, this wrench is largely hypothetical. Before the switch could be made, there had to be a plan in place—and this was a slow, seven-year process, full of tug of wars, inter-agency drama, and arguments over what exactly a catfish is. “Millions were spent, both agencies had responsibilities, and no catfish really got inspected,” Flynn wrote in 2014. The USDA didn’t look at its first fish until spring of 2016.

Despite these setbacks, some supporters of the bill have held the line. But Gibbons and others doubt their motives. “It’s a running joke in Washington that this has anything to do with food safety,” he says—instead, he casts it as a blatant attempt to undercut free trade. Plus, he says, individual catfish farmers are jumping ship, fearing that the regulations will make life harder for them, which Gibbons diagnoses as “a classic case of ‘be careful what you wish for.’” (Catfish Farmers of America did not respond to requests for comment.)

Meanwhile, nouveau catfish inspection has gained a lot of enemies on both sides of the aisle. The U.S. Government Accountability Office has deemed the program unnecessary ten times. Democratic Senator Jeanne Shaheen has repeatedly sponsored amendments that move toward eliminating it, along with Republican Senator John McCain. (In a 2013 article in Politico, McCain called the species in question a “crusty mudfish,” and accused it of being a “bottom-feeder with friends in high places.”) Other senators have accused it of violating various aspects of the World Trade Organization treaty, which would leave the U.S. open to disputes from other countries, and fear it may lead to boycotts on American goods.

Nowhere is this sentiment more apparent than at www.repealcatfish.com, a website dedicated to getting rid of the inspection program. Run by the National Fisheries Institute, the site contains a lot of convincing arguments for supporting the repeal—and, thanks to its smorgasbord of custom videos, cut-and-paste infographics, and heated slogans, it’s also a good way to viscerally understand exactly how fed up the regulation’s opponents are. There are multiple comparisons to the Emperor’s New Clothes, and an infographic entitled “The Twelve Days of Catfish,” which suggests that they would like you to bring this issue up at a Christmas party. “Unless you’ve been living under a rock, you know everyone’s urging Catfish Repeal,” the homepage promises.

Perhaps, in this divisive political age, catfish repeal will be what finally unites us. Maybe the controversy will land the U.S. in World Trade Organization court. Or maybe the catfish will remain stuck in limbo—neither cat nor fish, neither meat nor seafood, inspected either double or not at all. It’s hard to tell. As Flynn says, chuckling: “The more years it goes on, the stranger it gets.”

Naturecultures is a weekly column that explores the changing relationships between humanity and wilder things. Have something you want covered (or uncovered)? Send tips to [email protected].

Update, 1/5: The original version of this article called the catfish “unusually scaly”—they are actually unusually un-scaly, and have scutes instead. Thanks to @Serpentine202 for the correction, and we regret the errors.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook