State of the Union Speeches are a Global, and Sometimes Strange, Tradition

This 1523 illustration of the opening of British Parliament is the earliest rendering of a Speech from the Throne. (Image: Royal Collection/WikiCommons Public Domain)

At 9 p.m. on January 12th, concerned citizens the world over will turn on their televisions or open their laptops and give their attention to President Obama as he details his plans for the rest of his term, in the form of the annual State of the Union address.

But this is only one of dozens of speeches that will be given by world leaders in the beginning of 2016 to announce their particular goals. In Japan, the emperor recently read a short speech to mark the annual opening of the Japanese Diet, and Thailand’s king will have to do the same before the National Assembly can begin their next session. In the Netherlands, “Prinsjesdag,” or “Prince’s Day,” features a speech by the reigning monarch, who is brought to the Hall of Knights in a special golden coach, and until recently, Sweden began their legislative season with the Solemn Opening of the Riksdag–a ceremony steeped in Viking tradition that involved showing off the crown jewels.

The Netherlands’ Golden Carriage rolls through the streets during Prinsjesdag, the monarch’s traditional speechmaking day. (Photo: Minister-President Rutte/WikiCommons CC BY 2.0)

The English have retained perhaps the strangest customs: one particular usher, called the Black Rod, always has the door ceremonially slammed in his face, and the Yeoman of the Guard always checks the basement for explosives with a lantern, lest someone try to blow up Parliament again. The Queen also gets dressed in a room with Charles I’s death warrant hung on the wall, as a kind of built-in humbling mechanism.

The motivating idea–that leaders should give a regular report of their recent accomplishments and goals–has proved surprisingly flexible. Versions of the State of the Union have existed since the Middle Ages, and, antiquated door-slamming notwithstanding, most have been surprisingly good at evolving with the times.

The oldest agenda-setting speech still going belongs to the United Kingdom, where the annual opening of Parliament is marked by a ceremonial address outlining plans for the coming year. Like many British things, the tradition has a number of names, ranging from colloquial (“The Queen’s Speech”) to more deferential (“Her Majesty’s Most Gracious Speech”). Some historians think the general gist of this tradition dates back all the way to the medieval era, “when the Chancellor would explain to his Parliament the reasons and causes for its summons,” while others place its true origins around the 16th century, when monarchs held absolute power and needed a way to wield it expediently. These days, it is written by the cabinet and delivered by the Queen from her throne in the House of Lords.

Like the UK, many countries where figureheads now wield varying amounts of symbolic and political power have found ways to continue or modify old traditions. Canada, Australia, and other British commonwealths have the “Speech from the Throne” read locally by provincial governors. Under Sweden’s new system, the King ceremonially declares the Riksdag open–and then the Prime Minister takes over to set the agenda.

With its contemporary pomp and circumstance, the American State of the Union seems like a clear descendant of these so-called “Speeches from the Throne”–but it actually took hundreds of years to get that way. The United States Constitution requires only that the President “from time to time give Congress information of the State of the Union and recommend to their Consideration such measures as he shall judge necessary and expedient.”

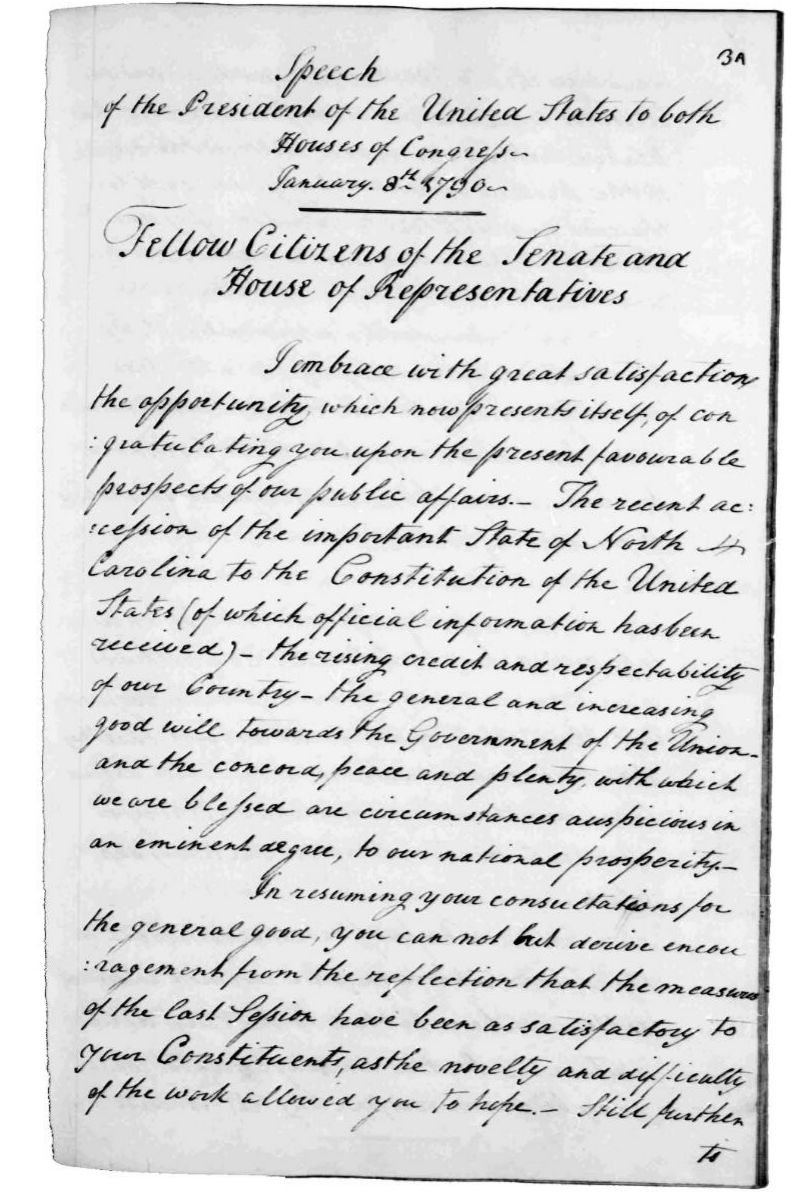

“There is no requirement that this be done in speech format,” writes Donna Hoffman, author of Addressing the State of the Union: The Evolution and Impact of the President’s Big Speech, in an email. The element of promise was also missing, says Hoffman: “Many of the 19th century messages were largely an amalgamation of executive reports.” Indeed, after a few rounds of brief annual catchup speeches by George Washington and John Adams, Thomas Jefferson famously refused to read his written statement aloud, saying oration of the sort was too slow, inconvenient, and monarchial. Instead, he wrote it down and sent it to Congress by courier, a tradition that endured until Woodrow Wilson decided to take the podium again in 1913. Even he, Hoffman writes, had a narrow audience in mind, focusing mostly on “facilitating the executive and legislative branches working together.”

Washington’s handwritten notes for the first State of the Union notes, from 1970. (Image: Library of Congress/Public Domain)

In the mid-20th century, technology expanded the State of the Union’s reach, helping it level up every couple of decades in pursuit of a wider audience. In December 1923, Calvin Coolidge broadcast his address on the radio for the first time, ensuring–as the New York Times put it–that his voice was “heard by more people than the voice of any man in history.”

In October 1947, Harry Truman became the first president to deliver the address on television; about 20 years later, in 1968, Lyndon B. Johnson moved his telecast to prime-time to further broaden his reach. Bill Clinton became the first to webcast a State of the Union in 1997, as he spoke hopefully about building the “second generation of the Internet.” Tonight, viewers can livestream Obama’s address via YouTube or Amazon while reading official annotations by White House insiders on Genius.

Though it still doesn’t have much pull in the polls, the State of the Union’s gradual widening of focus has been something of a bridge-builder, spurring national conversation and allowing the president to, as Hoffman puts it, “give the public information about what he has done for them lately.” More and more countries have set up similar traditions in recent years. Russia adopted the practice in 1993, and Nicolas Sarkozy delivered France’s first “U.S.-style state of the union speech” in 2009.

Indeed, countries that lack the tradition have begun asking for it: two years ago, legislators in Nigeria called for the country to begin mandating an annual address, citing Ghana as a precedent. “The address is used to keep the leader accountable and responsive to the citizens,” wrote reporter Acho Orabuchi in an op-ed, adding that it is “ideal for any nation that subscribes to good governance, strong democracy, and strengthening institutions.” From monarchical power trip to to democratic ideal, the state of the State of the Union reflects something of the state of the rest of the world.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook