This Terrible Mammoth Drawing Was a Giant Help to 19th-Century Naturalists

The first reconstruction from a flesh-and-blood mammoth looked more like a pig.

In 1799, a reindeer farmer named Ossip Shumachov began a strange yearly ritual. He was the leader of a community of Evenki, an indigenous group from the Russian North, and while hunting for wild reindeer with his family, he noticed a strange, dark lump poking out of the ice. Shumachov did not know what it was, wrote the invertebrate paleontologist I. P. Tolmachoff in his aptly-named 1929 paper “The Carcasses of the Mammoth and Rhinoceros Found in the Frozen Ground of Siberia.”

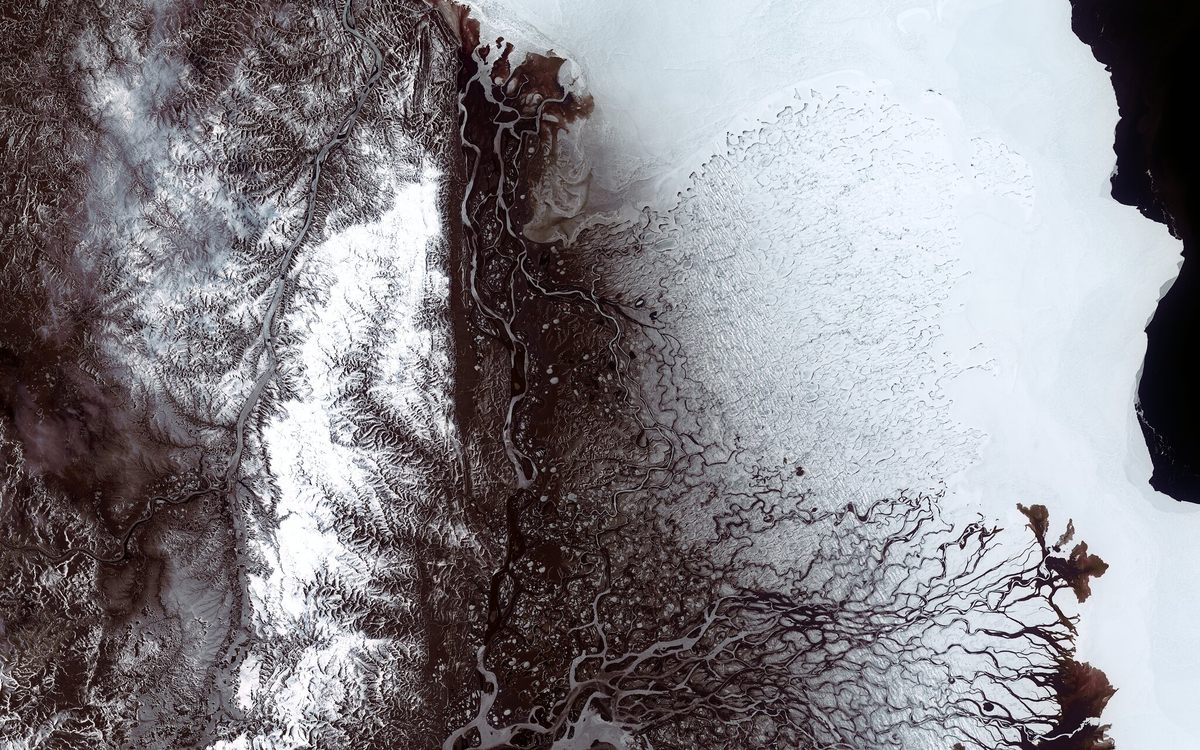

But Shumachov did know that Russia’s famously short summers thawed huge quantities of ice, resulting in a mile-wide river of meltwater, so he returned each year to this frozen mystery, waiting patiently for the mass to reveal itself. Five years later, it did. The long-dead and largely intact carcass of a mammoth had slipped out of the ice and onto the sand of the Lena River delta, Tolmachoff wrote. Shumachov, face to face with a prehistoric beast of the Ice Age, did what any enterprising person would do: He chopped off its tusks and sold them.

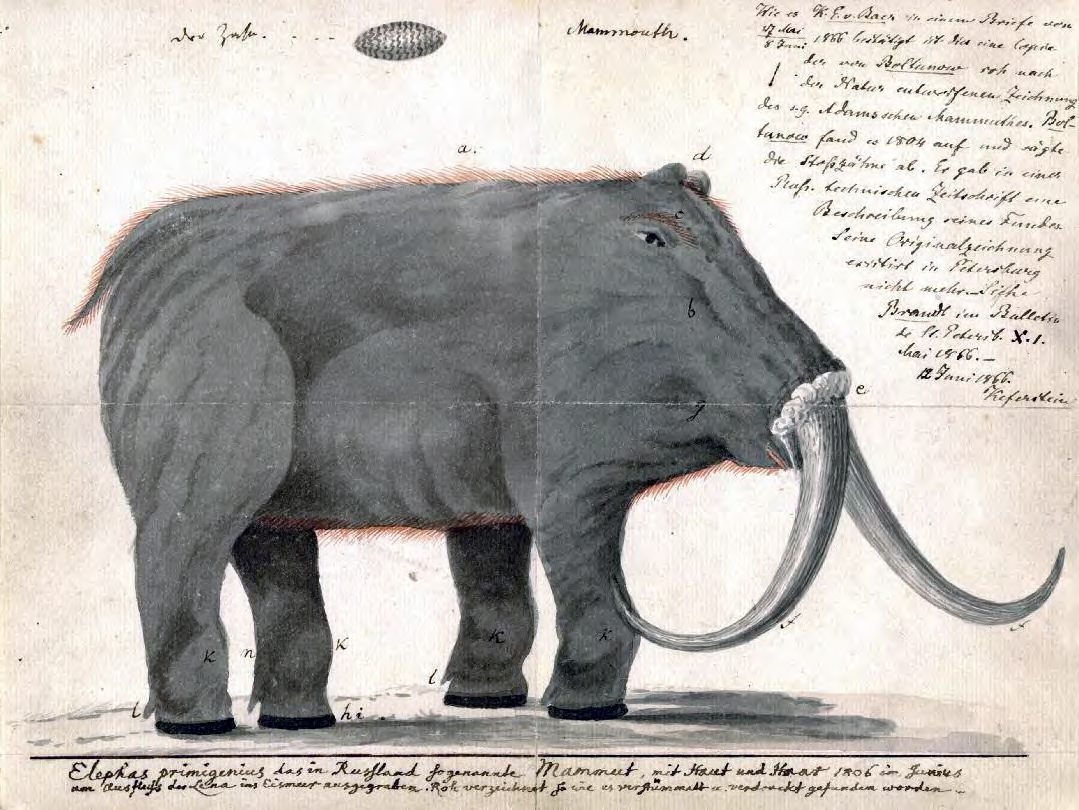

The man who bought the tusks, a Russian merchant by the name of Roman Boltunov, traded approximately 50 rubles worth of goods for the nine-foot-long tusks—more money than Shumachov’s village would have seen in several years, writes John J. McKay in his book Discovering the Mammoth. Boltunov was busy was making his way down the Lena River, selling and trading his wares, but he couldn’t resist mammoth tusks in good condition. Tusks weren’t rare in eastern Siberia, but these tusks were special: The man who sold them said he’d plucked them from an actual mammoth that was nearby, freshly exposed and rotting in the cool air. According to McKay, Boltunov convinced (or perhaps bribed) Shumachov to take him to the carcass. When the two arrived, Boltunov took some measurements on a sheet of paper and later, after leaving the mammoth, made a drawing of the creature from memory, Tolmachoff wrote.

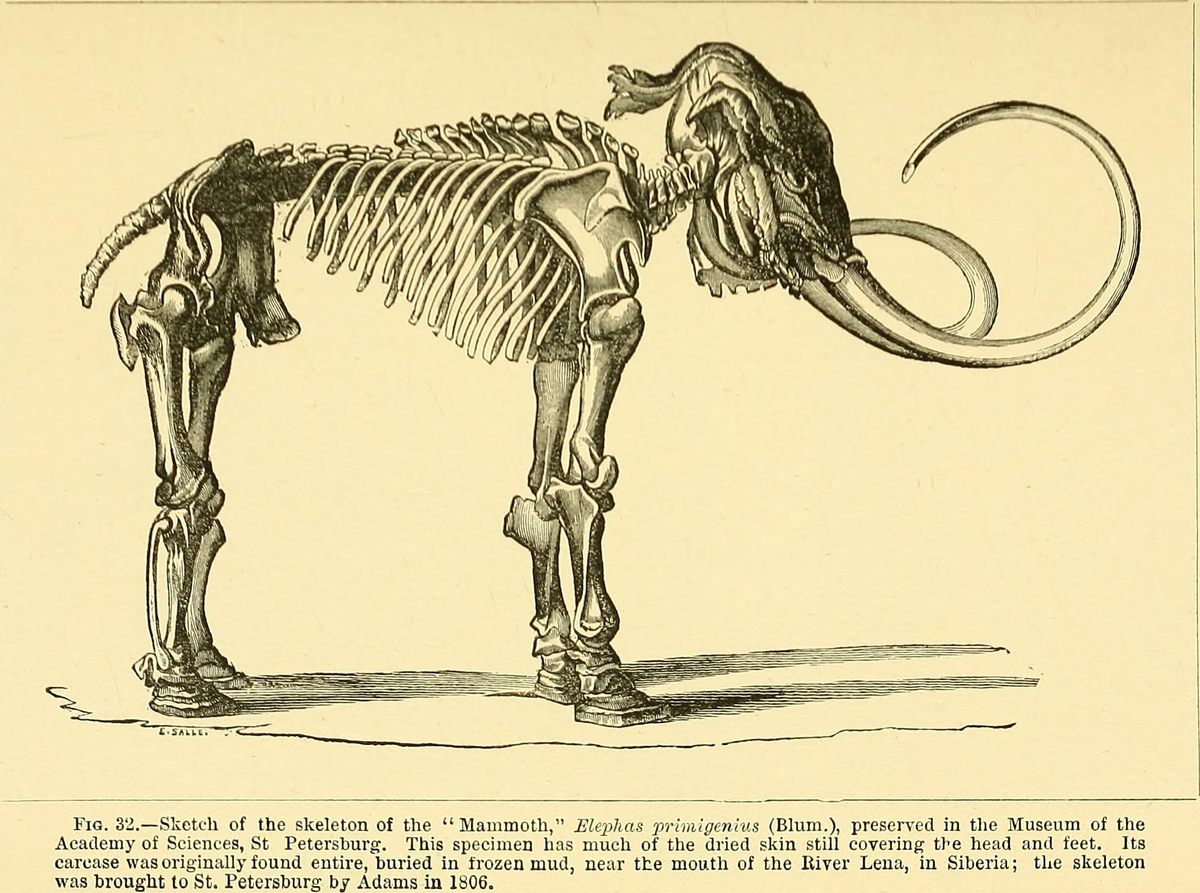

The drawing is crude, and depicts a strange swine-like creature with tusks pointing in opposite directions. The sketch “is a very good example of a reconstruction hindered by extreme ignorance of basic animal anatomy,” paleoartist Mauricio Anton wrote in an email. “The body and legs are shapeless, and each foot ends in a sort of hoof-like structure unlike anything seen in elephants (or any other animal).” Even so, this somewhat laughable caricature was the first reconstruction of a mammoth known to science that was based on more than bones, McKay writes on his blog Mammoth Tales. Much to the chagrin of stuffy Russian biologists, it played a pivotal role in science’s early understanding of mammoth anatomy.

When Shumachov and Boltunov reached the carcass, it had already been defaced, literally, by scavengers, as well as Shumachov’s dogs, according to McKay. Whatever meat was left exposed to air had been eaten, but the majority of the mammoth was still there: its fat body and trunk-like legs russeted in hair. Boltunov’s sketch did not faithfully portray the mutilated body in front of him, but rather imagined the mammoth in its prime, standing on all four legs.

Two years later, a merchant named M. Popoff sent Boltunov’s sketch to Mikhail Adams, a botanist at the Imperial Academy of Sciences. Adams rightfully described the drawing as “very incorrect,” McKay writes, but the drawing was still published in the Russian newspaper Technological Journal.

In the summer of 1806, led by Shumachov and ten other members of the Evenki tribe, Adams visited the site by the Lena River to recover the mammoth’s remains, as Adams writes in his 1807 travelogue “XXIII. Some account of a journey to the frozen sea, and of the discovery of the remains of a mammoth.” Unsurprisingly, Adams found an even more decrepit, putrefying corpse, one that was missing a leg, almost all its flesh and organs, its trunk and tail, and one of its forelegs. Undeterred Adams bagged all the mammoth he could, including two intact feet, one ear, a still-colored eye, and some preserved hide, the last of which required a team of ten men to drag it away from the sandy bank, he wrote. Adams also collected approximately a pood (a Russian unit of measurement for the weight of a kettlebell, the equivalent of 36 pounds) of the mammoth’s long hair.

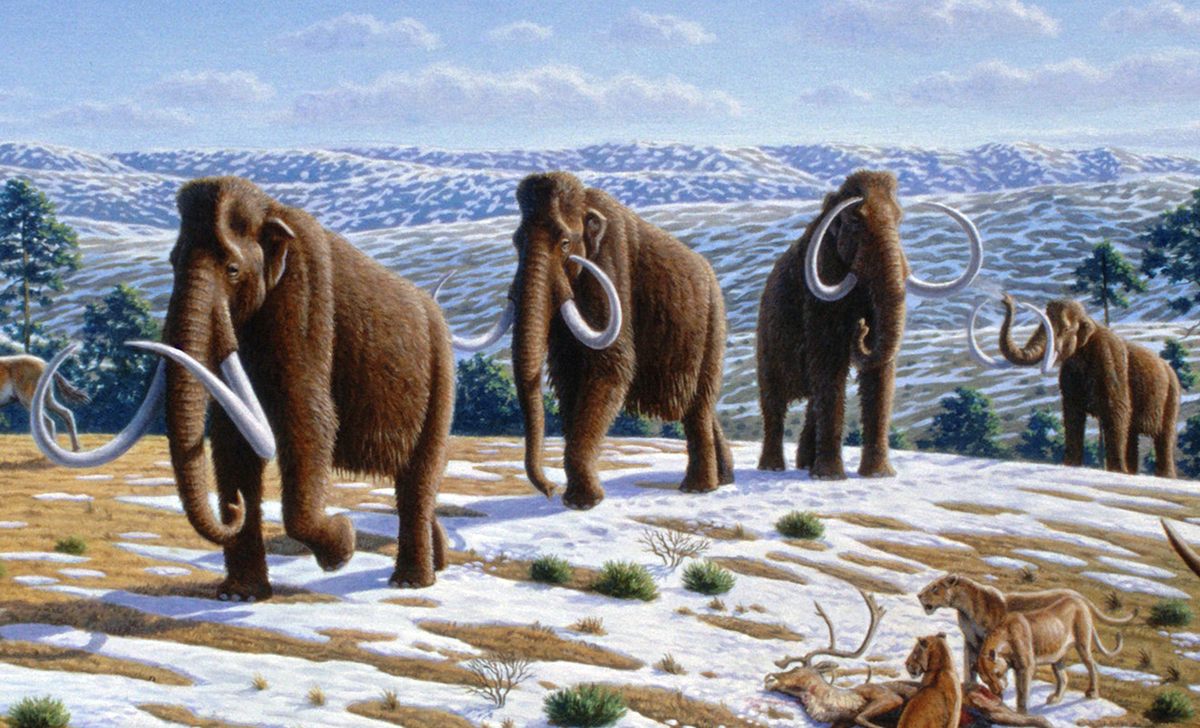

Though Adams was only able to scrounge up the meager, sloppy remains of the megafauna, the carcass represented the most complete remains known to science. It was just the fifth reported discovery of a flesh-and-blood mammoth, none of which had ever been recovered in time for European naturalists to study them. At the time, European naturalists knew the mammoth was an extinct relative of the modern elephant. Georges Cuvier, commonly called the father of paleontology, established extinction as a fact in a 1796 paper that compared the skeletons of Indian and African elephants against that of a fossilized mammal he would later name the mastodon, according to an entry on the Biodiversity Heritage Library blog.

Adams’ Siberian mammoth was missing one elephantine component: its tusks. So the botanist bought another set of mammoth tusks, passing them off for the originals, and sent everything to the Imperial Academy of Sciences in St. Petersburg in several packages. “The mammoth was the first complete carcass to be brought back to ‘civilisation,’ even if most of the flesh had gone by the time it reached St. Petersburg,” Adrian Lister, a paleobiologist at the Natural History Museum in London, writes in an email.

Several countries over, European naturalists had gotten word that a largely intact mammoth carcass had been discovered—though they were certainly confused by the drawing they received. In St. Petersburg, the German naturalist Wilhelm Gottlieb Tilesius got to work reassembling the skeleton. Adams had written his own account of the discovery, but he was a botanist, and had not even made a drawing. So Tilesius had only Boltunov’s sketch for reference, which he called “a poor drawing of a monstrous figure,” McKay writes. Aside from making the mammoth look like a pig, the drawing contradicted other narratives about the carcass, including Boltunov’s own notes. But the drawing preserved certain aspects of the body that had long deteriorated when Adams found it, such as the mammoth’s ten-inch tail and a shaggy coat of hair, which Adams mistook for a lion-like mane.

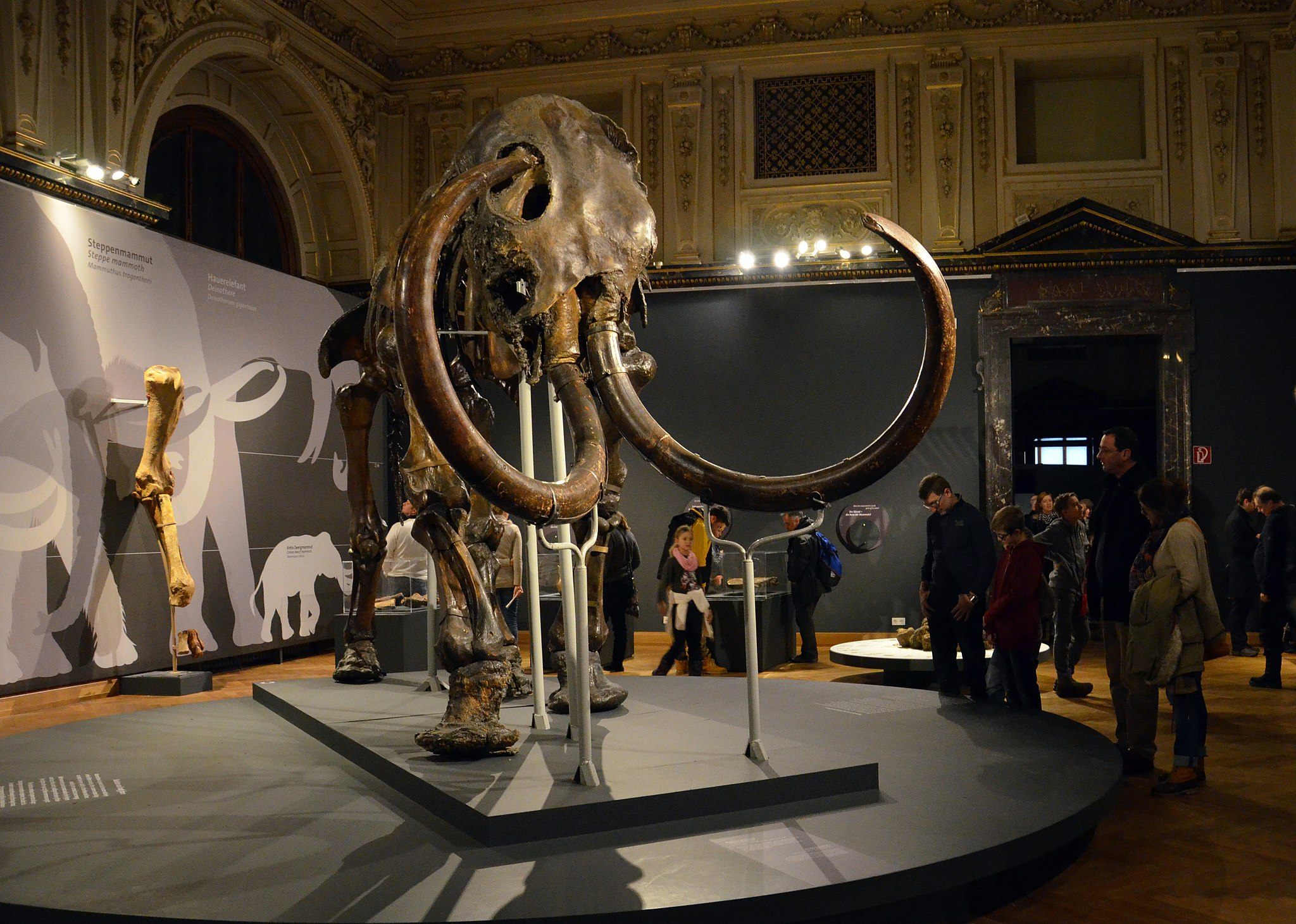

Tilesius ultimately based his reconstruction on the skeleton of an Indian elephant housed in the museum. Unsure where to place the enormous tusks, he guessed they pointed outward, like defensive weapons (they did not). The reassembled skeleton, over 16 feet long and 10 feet tall, went on display in 1808, making it the first mammoth skeleton ever to be mounted, Lister says.

In 1860, the Academy of Sciences created a leaflet offering 100 rubles to anyone who could produce a complete mammoth skeleton, a reward that could increase to 300 rubles if the carcass still had its meat and hide, Lister writes in Mammoths: Giants of the Ice Age. But the Adams expedition had left a bad taste in the mouths of local and indigenous people of Siberia. By taking 10 men from Shumachov’s village of just 40 or 50 people, McKay notes that Adams likely deprived the village of most of its adult men who would have needed to hunt during the summer to stock up for the harsh Siberian winter. In McKay’s eyes, even if the men were paid, they might not have had a choice in such a transaction, as the forced exploitation of indigenous labor propped up many scientific advances at the time.

According to Adams, Shumachov’s village also saw the discovery of a mammoth as a sign of future calamity. As Shumachov told Adams, the last time someone unearthed a mammoth in the area, their entire family died shortly after. With all this in mind, even 100 rubles seemed too meager a reward for such trouble. No preserved carcasses were reported for nearly a century; those found were kept secret or even chopped up into pieces and thrown into the sea, Lister writes.

Around the same time, unable to find another mammoth carcass, the German naturalist Karl von Baer tried to hunt down Boltunov’s fabled drawing. It had been lost long ago, but Baer tracked down a copy and published the reproduction in an 1866 paper with an attribution to Boltunov, noting the merchant’s contribution of key details of the carcass that Adams missed or never saw in the first place. According to McKay, every other paper that published the drawing used it as an example of the ignorance of rural Siberians, and entirely missed its scientific significance. There is no evidence that European scientists ever tried to contact Boltunov or Shumachov to interview them as witnesses to the original carcass. Shumachov even traveled to St. Petersburg to protest how Adams had taken sole credit for the mammoth he originally discovered. “Of course, cultural arrogance is hardly unique to that century,” McKay writes.

In the 21st century, considered alongside the bounty of mammoth carcasses scientists have discovered in dedicated expeditions to Siberia, Boltunov’s drawing does not hold up. It breaks the convention of anatomical drawings taken in the field, which should be rendered as the animal appeared in the ground. Mauricio Anton, who painted one of the most widely-propagated images of mammoths, politely eviscerated it. “The pioneer of paleoart, American artist Charles Knight, claimed that no one can pretend to be able to depict extinct animals if he or she is not able to draw modern animals competently,” he says. The Boltunov sketch “seems to be the work of an artist who could not be able to draw a modern elephant, or even to describe it.”

But no one ever expected the Boltunov drawing to be anatomically accurate, or even good. To paleoartist Brian Engh, who painted a mural of Pacific mastodons in the Western Science Center in Hemet, California, Boltunov’s sketch is actually commendable. “What that artist did is basically a simplified version of the process we paleoartists go through when reconstructing prehistoric animals,” he says. “We look at the available fossil remains and try to figure out the animals in question is related to. We then try to clothe that skeleton in soft tissues from the closest relative where soft tissues are known.” Defending Boltunov, Engh points to certain pig-like features in elephant skulls, such as a flat snout, big molars, and front-facing tusks.

As a paleoartist, Engh says he’s constantly surprised by how unfamiliar people are with the skeletons of common animals, even those we eat. “I’m constantly amazed by the myriad ways that subtle differences in soft tissue can result in a significantly different looking organism,” he says. Consider birds, for example, which can have eerily similar skeletons but look drastically different in real life, once coloration, plumage, and wattles are taken into consideration.

Today, the skeleton, known as the “Adams mammoth,” stands on display at the Natural History Museum Vienna. Its mummified skin still clings to its head, and the tips of its tusks now rightly spiral inward. Boltunov’s drawing, meanwhile, is still reproduced in textbooks. While the sketch does technically fall under the realm of wonky paleoart, it also represents an earnest attempt at citizen science that was, in its time, laughed off as an example of how little rural Siberians knew. Boltunov did the best he could to capture a beast that must have seemed almost mythic, from an age scientists still have yet to entirely understand.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook