The Bizarre 17th-Century Dioramas Made from Real Human Body Parts

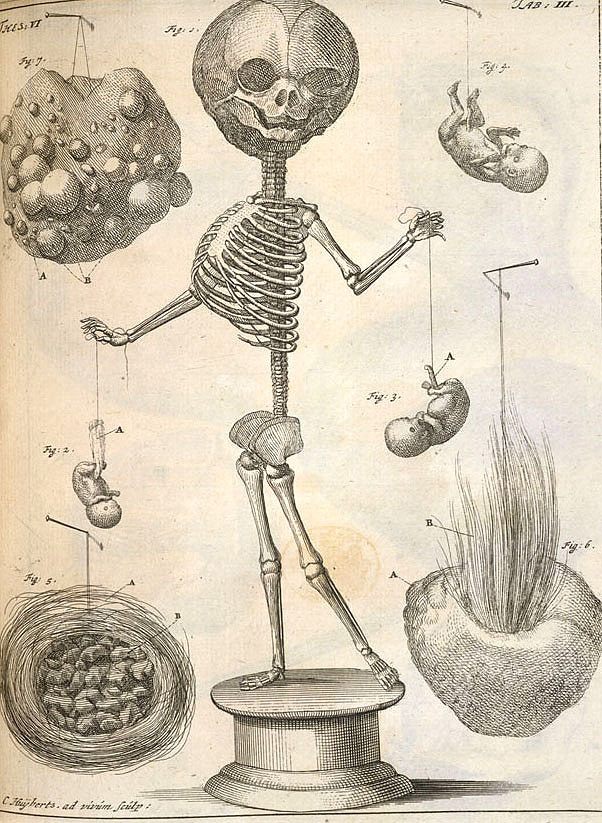

Dioramas of infants’ skeletons adorned with lace and jewelry were seen as grotesque and beautiful.

In 1689, on the canal Bloemgracht in Amsterdam there was a museum that showcased preserved anatomical specimens in a peculiar manner.

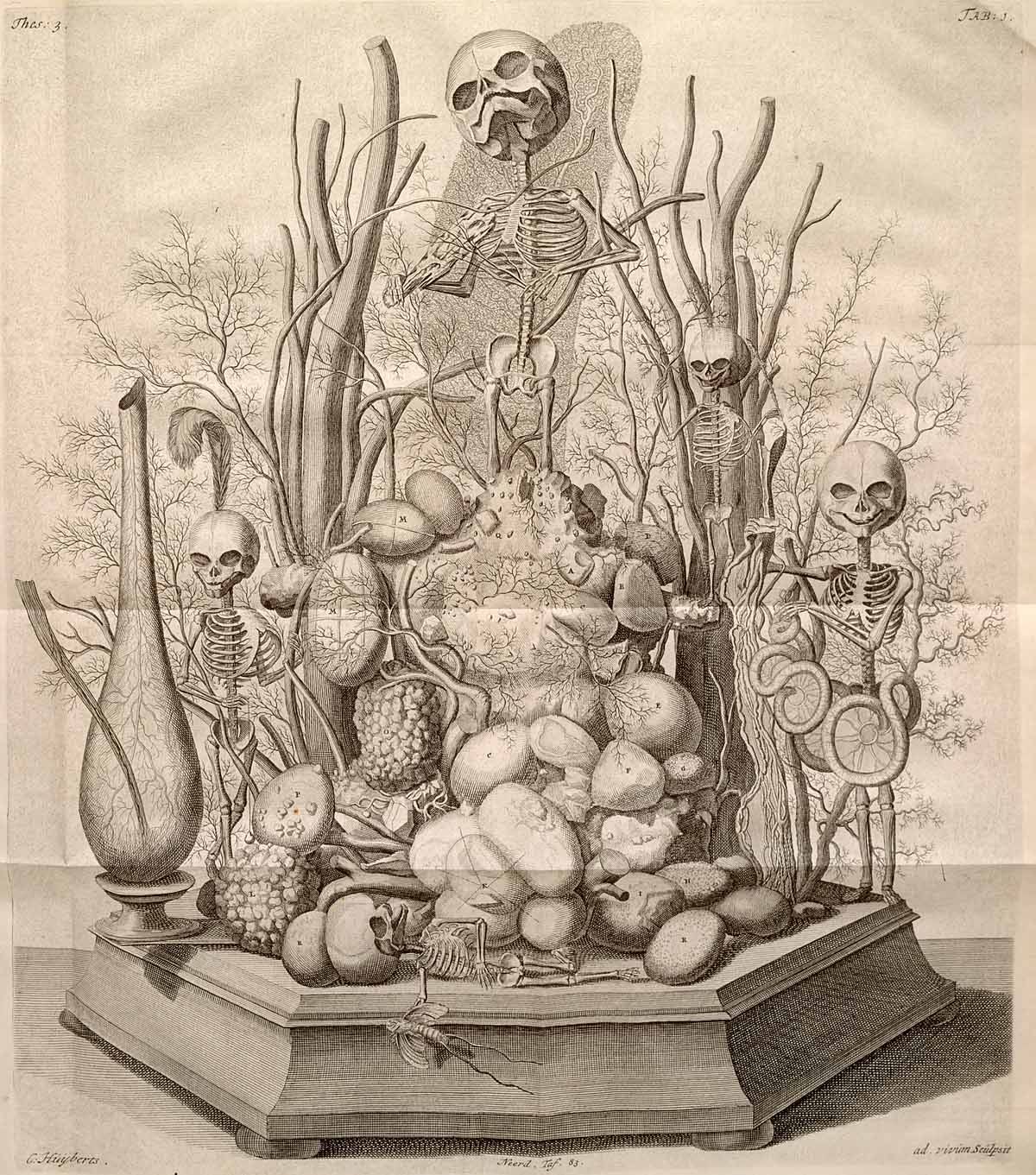

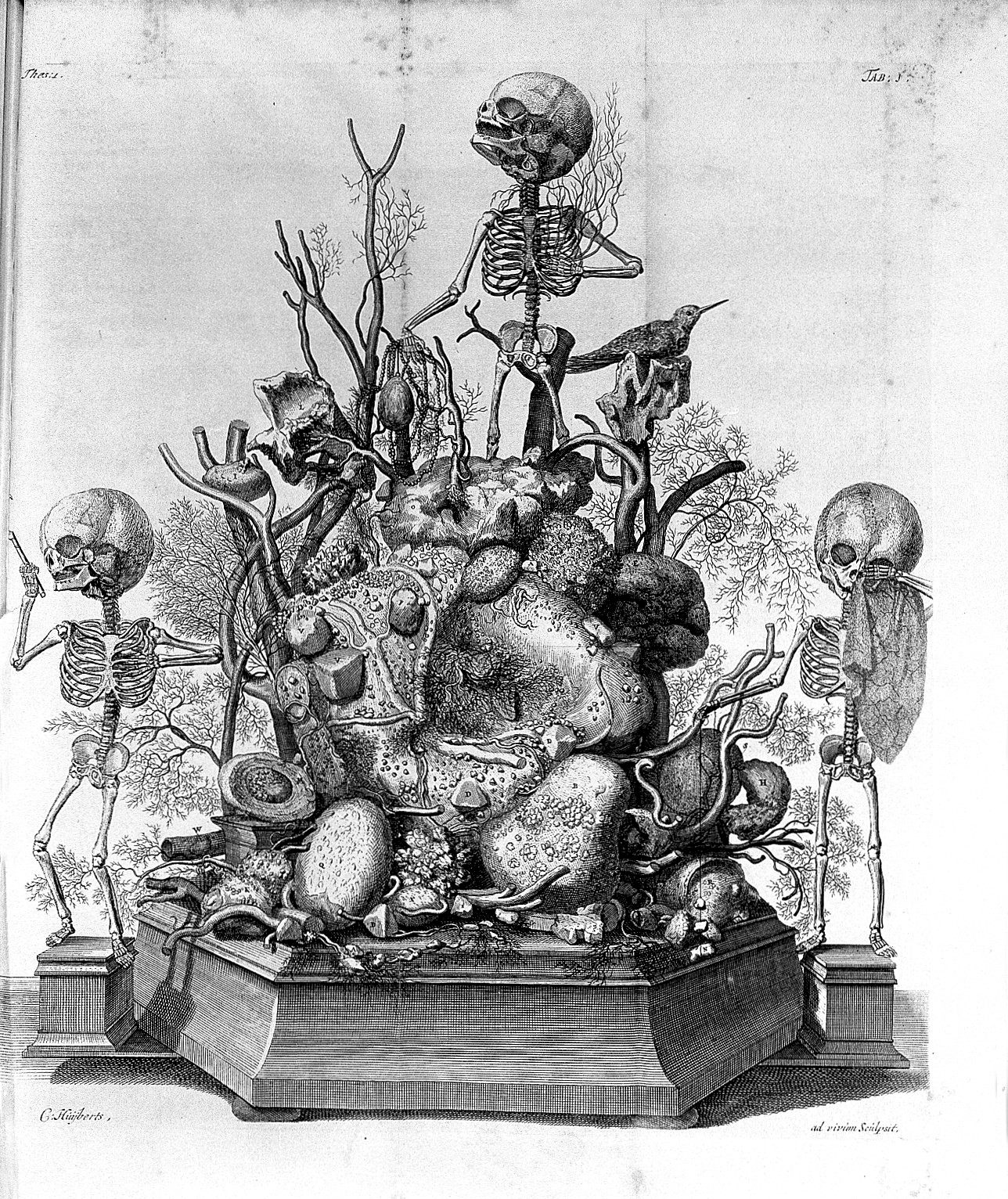

Among jars of embalmed specimens, there were several startling dioramas containing skeletons of infants adorned with delicate and morbid decor. In one of the pieces, depicted below, five skeletons are carefully positioned on a vase foundation made of inflated tissues from human testes. There was a feather headdress, a girdle of sheep intestines, and a spear made of the hardened vas deferens of an adult man.

The skeleton standing at the top of the pile of preserved human remains holds a piece of bone like a violin and a dried artery for a bow. Its head tilted towards the heavens is coupled with the inscription, “Ah Fate, ah Bitter Fate!”

The skeletal scene is from one of Dutch anatomist Frederik Ruysch’s several dioramas, or tableaux—fetal skeletons arranged in still-life positions atop a landscape of preserved plants, bones, and embalmed tissues. Ruysch’s Amsterdam museum was like a 17th-century version of the recent blockbuster exhibition, Body Worlds, by Gunther von Hagen. He treated science as an art, pushing the practice of specimen preservation while arranging his pieces to make a commentary on the beauty of life and death.

He would juxtapose the macabre contents with flowers, beads, jewels, and lace to “allay the distaste of people who are naturally inclined to be dismayed by the sight of corpses,” he once wrote. “I do it to preserve the honor and dignity of the soul once housed in the body,” Ruysch said.

Ruysch’s displays attracted medical professionals, political leaders, and the general public, receiving mixed reactions of fascination and disgust. In addition to his collection, Ruysch used notable preservation techniques, such as wax injections, to maintain the structure of blood vessels, and created a secret embalming liquor that kept specimens looking lifelike.

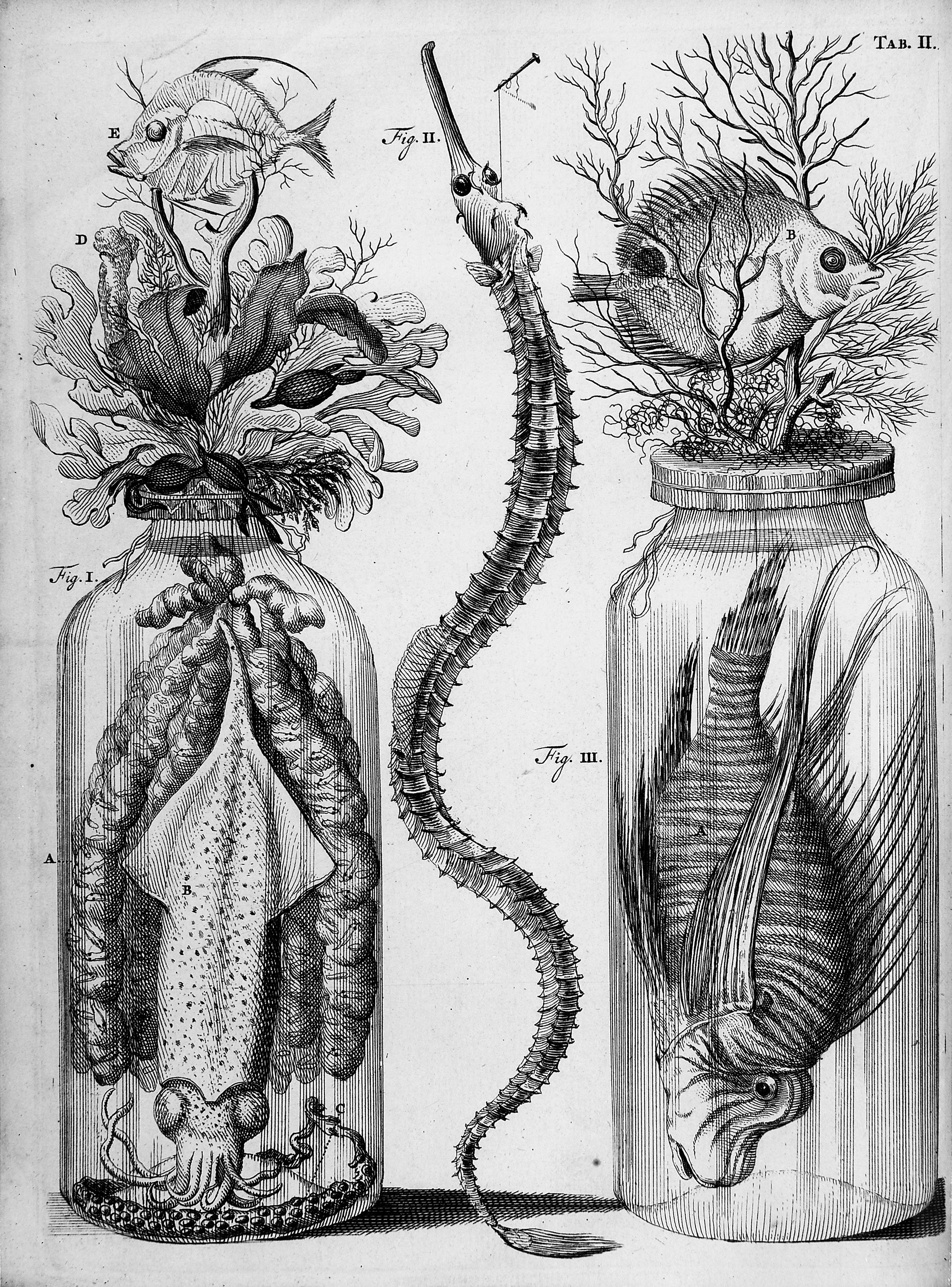

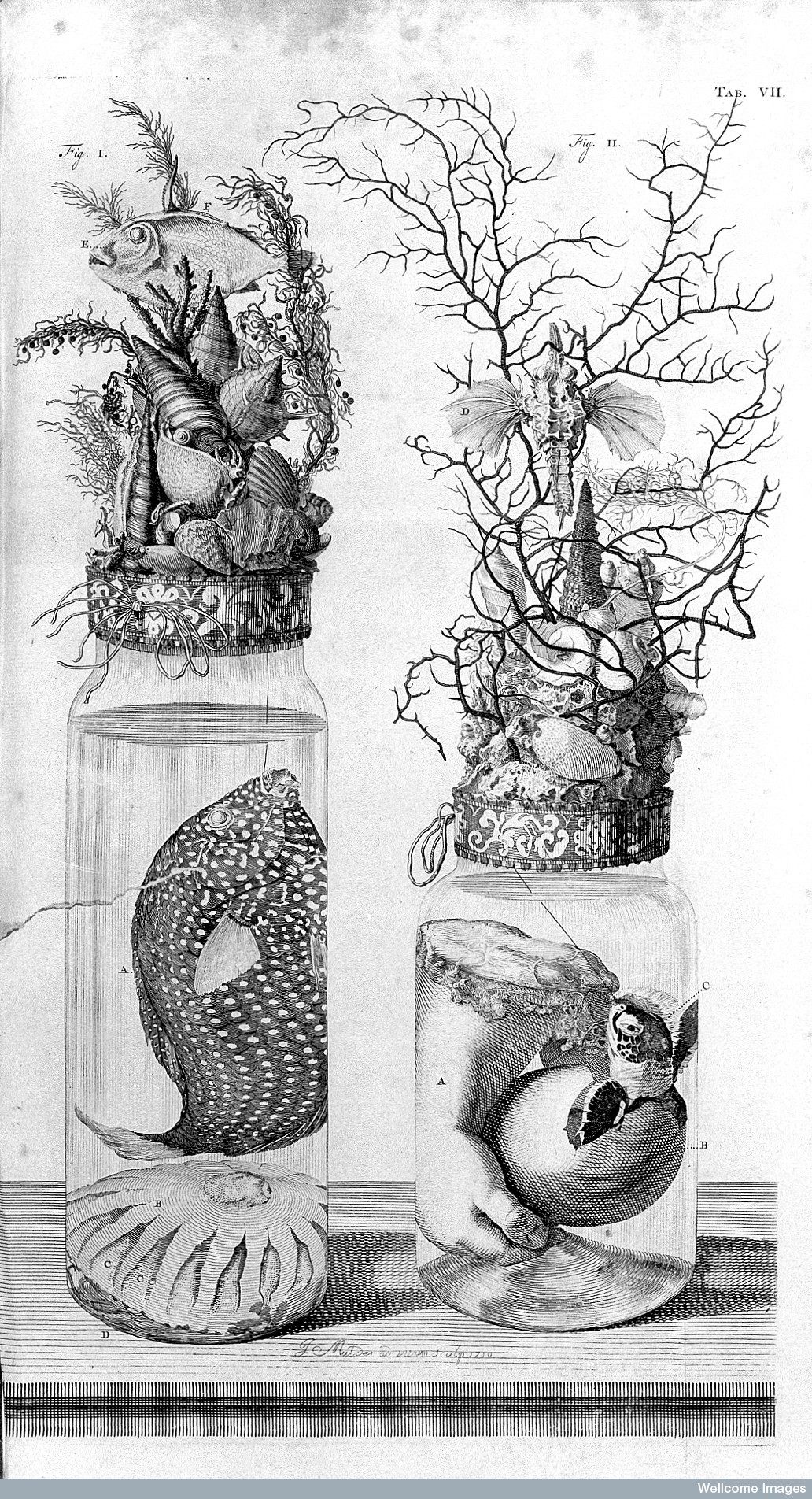

While he is most famous for his hauntingly beautiful dioramas, his museum also contained quality preserved specimens ranging from exotic plants, squid, and butterflies, to human embryos and brains, which were later drawn in his book Thesaurus anatomicus— or “anatomical treasures.”

Born in 1638 in The Hague, Netherlands, Ruysch grew up exposed to foreign flora and fauna that travelers would bring back to Europe to trade. He first became interested in plants and received training at an apothecary, which led him to start collecting different plants, rocks, insects, and eventually human bones. Ruysch later became a fellow at the Amsterdam Surgeon’s Guild in Anatomy, and by 1690, he was regularly dissecting, embalming, and mounting preparations.

In the late 1600s, Ruysch decided to share his anatomical works with the public, renting out a series of small houses in Amsterdam for the museum. His collection continued to grow, “and so I was forced to start a second room, and this one also being insufficient, a third,” he said.

The museum was overflowing with more than 2,000 specimens. While the anatomical collection was the centerpiece, he had two separate rooms dedicated to dried plants and “strange creatures” filled with fish, insects, and other flora and fauna from Asia, Africa, and America. When visitors entered, they were immediately greeted by a tomb of various skeletal remains—bones of children who died too young. One skull of a newborn baby bore the saying: “No head, however strong, escapes cruel death.”

“Ruysch’s presentation of his anatomical collection was in keeping with a tradition in which depictions of skulls and skeletons served as reminders of death,” Luuc Kooijmans writes in the book Death Defied: The Anatomy Lessons of Frederik Ruysch. “He impressed upon his visitors that death could strike at any moment, and that they should be ready to face it with a clear conscience.”

Ruysch ran the museum as a family operation. He would hold classes and provide information to physicians and medical professionals himself, while his daughters would give tours to the general public, who paid a small admission fee. One of his daughters, still-life artist Rachel Ruysch, even assisted with the dioramas by sewing the lace garments and tiny batiste sleeves.

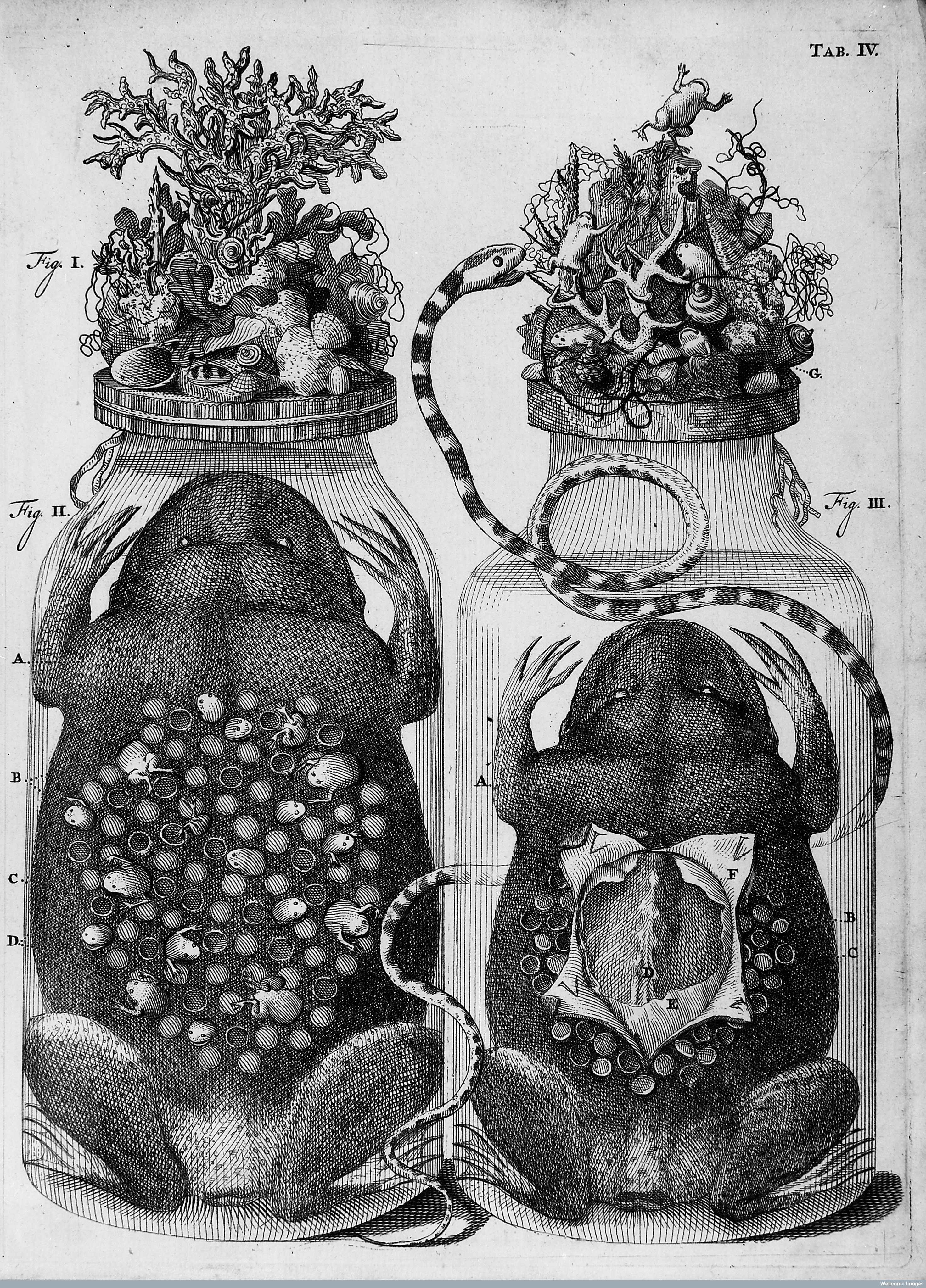

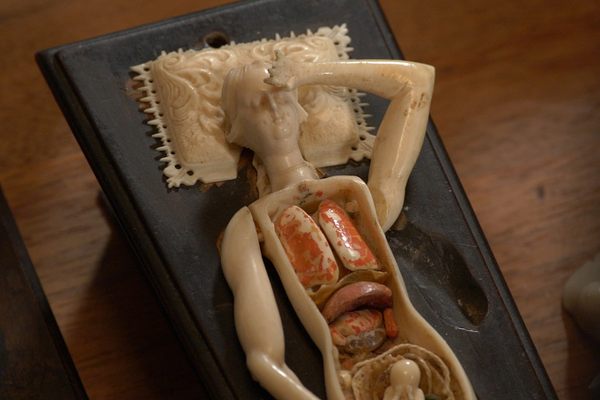

Some fetal heads were given lace collars, and the blunt ends of embalmed limbs wore textiles and fabrics, writes Britta Martinez in the Embryo Project Encyclopedia. Many of the skeletons are seen holdings jewels in their boney hands or strings of pearls. Ruysch also took to decorating the lids of preservation jars—a floating human hand cradling a hatching reptile topped with seashells, dried corals, butterflies, and flowers. By mixing exquisite plant arrangements with the human specimens, Ruysch hoped to soften the sight of morbid body parts for those who found it grotesque and unsettling.

The decorations “put the horror in perspective by stressing the transience of life, by showing that the body was no more than an earthly frame for the soul,” Kooijmans explains.

However, his designs were met with some criticism. In a pamphlet published in 1677, one opponent ridiculed Ruysch’s artistic dioramas, and claimed that he couldn’t see how the displays could inform anything about anatomy:

“He paints snakes to portray his venom; he paints toads to express his poisoned nature…he paints lobsters to portray his crabbiness… he paints trees and woods to chase the officers into them; he paints flowers to learn that all his fine works perish as easily as a wildflower.”

Ruysch’s contribution to anatomy is often overshadowed by his elaborate tableaux. He spent much of his time experimenting with embalming methods that would better preserve soft body parts, which lose their color and quality over time. One technique he helped refine was the art of preserving the tiny veins, arteries, lymph vessels, and nerves that run throughout the body.

In 1697, he successfully injected a wax-like fluid that was thin enough to seep into the smallest branching capillaries. The fluid would then solidify, preserving the shape and structure.

“All those arterial vessels fanning out into the internal organs and going straight into the veins,” Ruysch marveled.

This technique would be performed on deceased humans and animals to better visualize vessels and blood flow. Ruysch applied the injection on the cerebral cortex, which helped others understand its structure, writes Sidney Ochs in A History of Nerve Functions: From Animal Spirits to Molecular Mechanisms.

Physicians also praised Ruysch for the lifelike color and elasticity of his specimens. He achieved this greater quality through another liquid invention he called “liquor balsamicum,” a clear embalming liquid that took him 34 years to perfect. It made the specimens “as hard as stone and imperishable, but changed them a great deal in color and shape,” Ruysch wrote.

Ruysch never divulged the recipe of liquor balsamicum. After his death in 1731, at the age of 92, various chemists attempted to reproduce it but the results were unimpressive. In a book published in 2006, his secret liquor balsamicum has been revealed to contain clotted pig’s blood, Berlin blue, and mercury oxide, according to Erich Brenner in the Journal of Anatomy.

In 1717, Ruysch sold his anatomy museum (and secret liquor recipe) to Tsar Peter the Great, who had been an avid patron and fan of his work. His pieces still exist in the Kunstkammer of Peter the Great in Leningrad Academy of Science, and are immortalized in the illustrations of Thesaurus anatomicus.

Ruysch’s fetal tableaux are bizarre, but he believed that they served a scientific purpose, writes Antonie Luyendijk-Elshout. Ruysch firmly stated that he could bring a dead person back to life through his embalming practices, as if “almost nothing is missing but the soul.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook