An American Boat Sailed to Vietnam During the War. Then It Disappeared

The Phoenix of Hiroshima has had a long, strange trip.

Al Hugon was lying on the carpet of his vacation home in Santa Cruz, California, staring up at a bookshelf. It was late summer, 1997, and news coverage of Princess Diana’s death was the only thing on TV. Hugon, who ran a printing business in the Bay Area, was gently pestering his girlfriend to move onto his 50-foot sailboat with him.

When Hugon had purchased the boat seven years earlier at an auction, a piece of plywood covered a hole in its hull. Lumber was piled on the deck. But despite its sorry shape, Hugon says the boat “just felt right. It smelled good and it felt right.”

He bought it for $2,500, then spent $8,000 swapping out rotten planks, the rudder, and hinges. He rebuilt the engine and replaced the water tanks. Once, while the yacht was dry-docked, an old-timer asked if he’d found any bullet holes in the hull—there were rumors the boat had been fired at during the Korean War—but Hugon never spotted any. He did notice that the stairs, the archway, and the original planks were all carved by hand.

Hugon’s girlfriend was firmly opposed to moving onto the yacht. She couldn’t envision her three kids, Hugon’s daughter, and the pair of them crammed inside a cabin the size of their living room. “We’re not all going to live on that boat,” she insisted. As she spoke, Hugon noticed a title on his bookshelf: All in the Same Boat.

Written by American anthropologist Earle Reynolds and his wife, Barbara, All in the Same Boat describes the around-the-world trip their nuclear family took in a 50-foot sailboat named Phoenix of Hiroshima. Living on a yacht smaller than a subway car, they visited major ports and uninhabited islands.

Hugon picked up the book. The descriptions of the Phoenix sounded familiar. He flipped to the photographs and saw that the roof and the planking were hand carved. “I knew it all,” Hugon says. “I’d sanded it and painted it.”

He turned to his girlfriend, astonished: “This is my boat.”

Leaving Japan, 1954. (All Photos: Courtesy Jessica Renshaw)

The story of the Phoenix begins with a man named Earle Reynolds, who had always dreamed of sailing around the world. In 1951, the physical anthropologist left his job at Antioch College in Ohio and moved with his wife and three children to Hiroshima, Japan, to study the effects of radiation on atomic bomb survivors. For the first time in his life, Earle lived by the ocean. By day, he examined survivors of the blast. By night, he fantasized about setting sail.

Born to circus performers in 1910, Earle was naturally equipped with a sense of adventure. He was also ambitious: He often told people he was the first child in his big-top “family” to get a college degree, earning a Ph.D. and becoming an expert in human growth and development. In Japan, he’d return home from work every night and research sailboat construction. A boat maker in Miyajimaguchi built a ship according to Earle’s plans, working by hand with saws, adzes, chisels, and hammers. Eighteen months of labor later, the family moved onto the Phoenix of Hiroshima. They planned to sail around the world.

“We gave the dog away—traded it in for a tricolored cat—sold our woody station wagon,” says Earle’s daughter, Jessica. As the skipper, Earle assigned each shipmate a role. Barbara, a published author, was in charge of cooking, provisioning, and education. Ted, their 16-year-old son, was the navigator. Jessica, 10, was the “ship’s historian” and kept a journal. (She embraced the voyage after her father promised that her dolls could have their own cubby.) Three Japanese men with some sailing experience signed on as crew members.

Before a crowd of well-wishers, the Phoenix left Hiroshima Harbor on October 4, 1954. The first stop was Hawaii—about 4,000 miles away.

Jessica Renshaw with her father, Earle Reynolds.

“To our hundreds of friends the whole venture was nothing less than a gallant form of suicide,” Earle wrote in All in the Same Boat. He had no sailing experience. He didn’t know if he’d get seasick. He’d only recently discovered that boats don’t have brakes. Earlier that year, when the Phoenix touched water for the first time, Earle crashed the yacht into another boat watching in the harbor.

Then, in an early test run, the crew failed to realize the anchor had been dragging the whole time. “I never put it together that they didn’t know what they were doing,” Jessica says.

Within 12 hours of setting sail for Hawaii, the barometer fell. A storm rocked the ship as waves crashed over the deck. Anything that wasn’t tied down went airborne. Jessica and Barbara stayed below deck and listened. “The ship groans with a thousand voices,” Barbara wrote in her journal. She found Jessica in her bunk buried under toys that had fallen from their cubbyholes.

The crew settled into a rhythm during calmer weather. They watched dolphins play in bioluminescent waters and made a game of lassoing albatross. In Bali, they watched a 17-year-old girl get her canine teeth filed down. In Huahine, a French Polynesian island, they held the skulls of former chiefs. Earle got a permit to take two animals of every kind from the Galapagos Islands, and the family sailed with a baby goat and a tortoise named Jonathan Mushmouth, whom they acquired in exchange for instant milk, hot pepper sauce, and a can of shortening.

Near Tahiti, 1955.

The Phoenix traveled from Hawaii to the Polynesian Islands, through the Tasman Sea into the Indian Ocean, around the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa, to South America, the Caribbean, New York City, through the Panama Canal, the Galapagos Islands, and back to Hawaii. They stopped in ports like Sydney and Cape Town and dozens of sparsely populated, relatively undeveloped places where people spoke pidgin and native languages.

Most locals they encountered were curious and hospitable. The Japanese crew members, however, were often regarded with disdain and barred from entering white-only yacht clubs. On board, there was less racial animus, though the family did refer to the Japanese crew members as “boys.” Earle—who knew that the crew saw him as “cautious to the point of obsession”—chastised the sailors for not following orders. The final straw came when he reprimanded a crew member for steering the boat while sitting. Two of the men left the yacht and returned to Japan.

“In many ways Earle was a cynic,” his friend Bob Eaton says. “A cynic with high hopes.” All in the Same Boat gives occasional glimpses of those “high hopes.” Cruising from the Java Sea to the Indian Ocean, Earle describes “the thrill I sometimes felt, lying in my bunk and listening to the whisper of water flowing past, in thinking, ‘I’m doing it!’ ” He continued, “This is my ship, my life, my adventure, and nobody can take it away from me!”

But the ship could, and would, be taken away from Earle. Before the final leg of its trip, the Phoenix would be wrenched from his control and thrust into the Atomic Age.

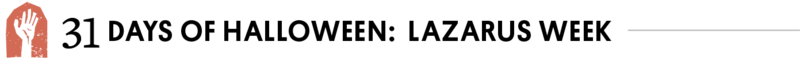

The arrival of the Phoenix in Hawaii made headlines.

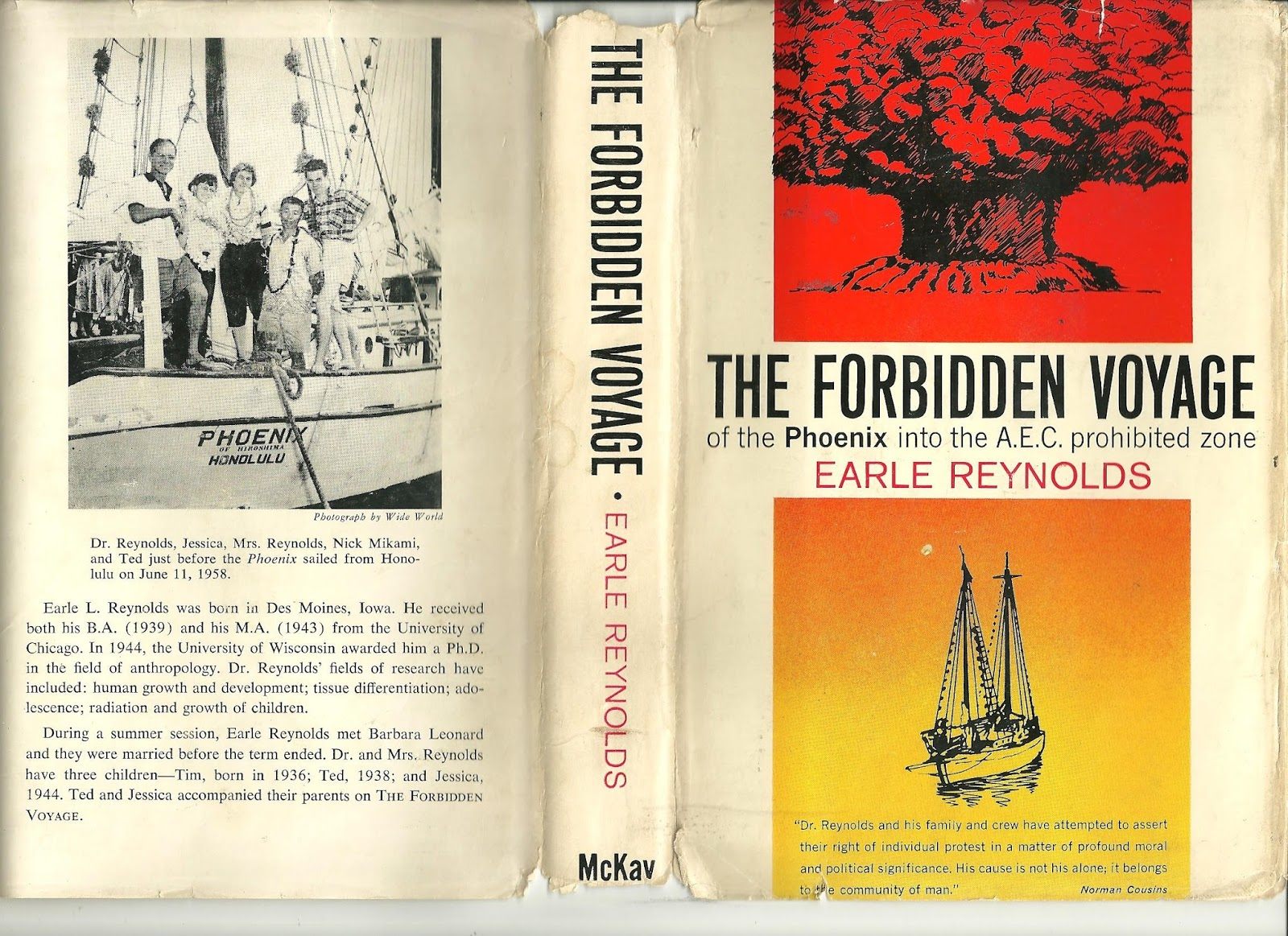

The Phoenix sailed into Hawaii on April 9, 1958. The boat had been at sea for three and a half years and traveled 50,000 miles, but “we were disappointing copy—no shipwrecks, no brush with cannibals, no mutiny, no piracy—we just sailed around the world and came back,” Earle wrote in his 1961 book, The Forbidden Voyage.

Nearby, the Quaker crew of a 30-foot sailboat called the Golden Rule was generating more exciting press. A Christian denomination with a legacy of pacifism, Quakers had been conscientious objectors to the First and Second World Wars. Now the Golden Rule was planning to sail some 2,500 miles to Bikini Atoll to protest nuclear weapons testing. It was a direct response to an Atomic Energy Commission regulation forbidding American citizens from sailing through the zone.

Earle thought the crew of the Golden Rule were “crackpots” for taking on the government. He was uncomfortable with religion and civil disobedience, but Barbara disagreed. She invited the Quakers for dinner. “Nuclear explosions, by any nation, are inhuman, immoral, contemptuous crimes against all mankind,” one member explained to the family.

Having lived in Hiroshima, Earle had seen the damage an atomic bomb could do. He suspected that nuclear weapons testing was unsafe and believed that the United States could not legally restrict sailing on international waters. His feelings began to change. On May 1, 1958, the crew of the Golden Rule left Ala Wai Harbor, only to be stopped five miles offshore and sent back. A month later, on June 4, they tried again. This time they were arrested and sentenced to 60 days in prison.

The Golden Rule in Hawaii, 1958, just prior to its departure for the Bikini Atoll to protest nuclear testing.

Now that the Quaker crew was in jail, Earle considered carrying on their protest. After all, the Phoenix had been built in Hiroshima. Niichi Mikami, the remaining Japanese sailor, was a native of Hiroshima. Jessica and Ted threw their support behind the mission. “It was like we were the only people in the world that knew about these dangers, the only people who could do anything about them,” Jessica says. Earle knew that protesting the government would end his academic career. Still, he and Barbara decided to sail.

Feeling “the pressure of the world,” the Phoenix took off June 11. They brought charts, a medicine chest, a radio, and a box of respirators from the Golden Rule. “What a pitiful protection against radioactivity!” Earle wrote. “How does one divide four masks among five people?” He knew he’d never open the box.

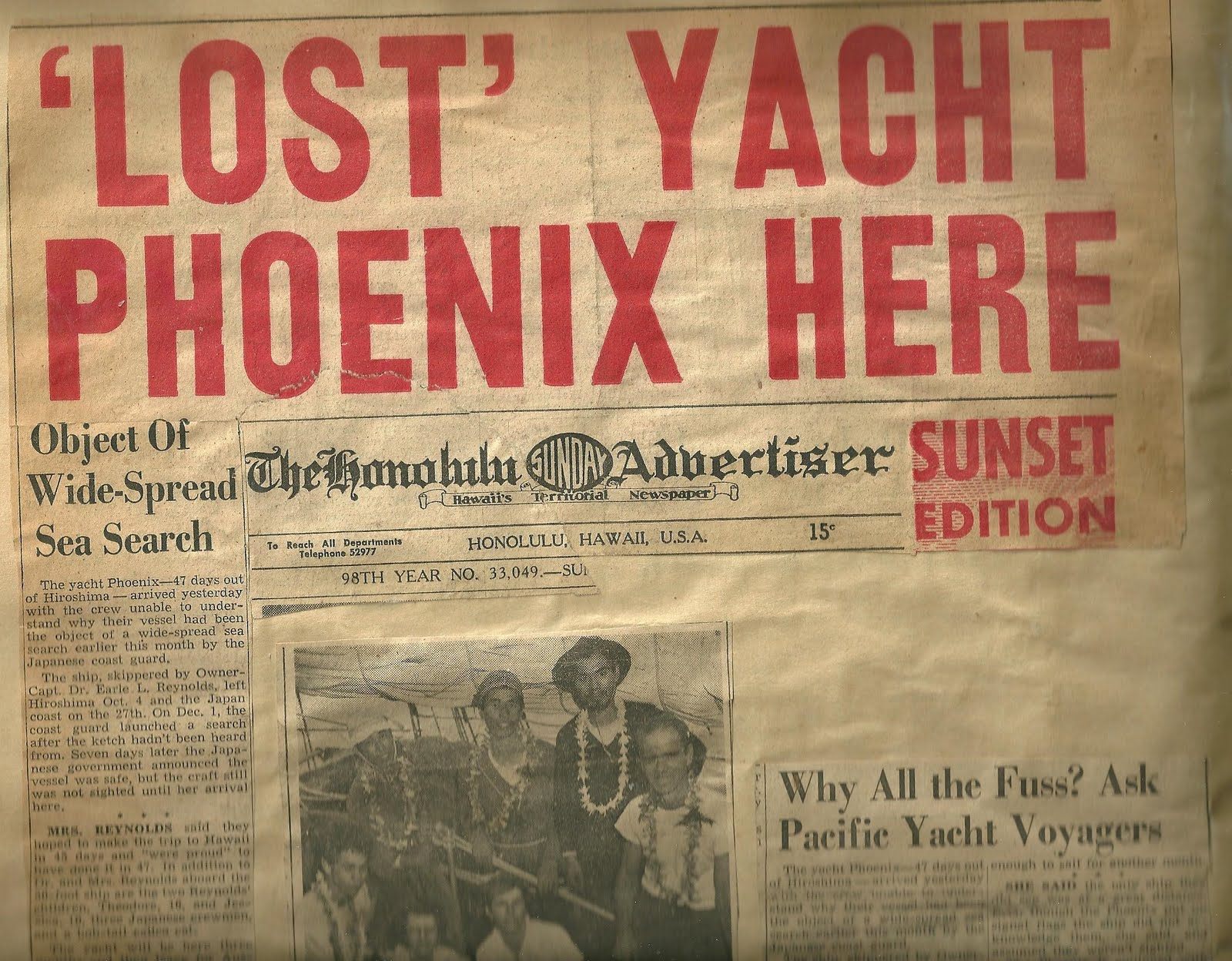

For three weeks, the Phoenix sailed in mild weather. When they approached the test zone, Earle announced his intention to enter. No response. The next day, a military ship approached—they’d been monitoring the Phoenix all day but had ignored their calls. Armed officers arrested Earle and ordered him to sail to Kwajalein military base. Shortly thereafter, they saw a dirty orange flash, illuminating the clouds.

The USS Collett alongside the Phoenix as they sailed to Kwajalein.

Earle was charged with “violating, attempting to violate, and conspiring to violate a regulation”—a crime that carried a possible 20-year prison sentence. Newspapers wrote regularly about Earle’s legal battle, and while some called his actions un-American, donations poured in from across the country. Earle was convicted but won an appeal, and was acquitted without serving jail time. The family left Hawaii for Hiroshima and arrived on July 30, 1960, making Mikami the first Japanese person to sail around the world on a recreational vessel.

The Phoenix didn’t stay in port for long. The family took a trip across the Sea of Japan to Nakhodka, Russia, to protest Soviet nuclear weapons testing. When they couldn’t dock, Barbara made the decision to turn around without consulting her husband. On the way back, the rudder broke, and the boat almost crashed into rocks.

“When we went into the test zone, expectations formed,” says Jessica. “Japanese people said, ‘You’re our voice in America. We look to you for nuclear war to end.’ We internalized that.” Barbara and Earle’s relationship fractured, and the couple divorced in 1964. According to friends and family, once the relationship ended, Earle rarely spoke of Barbara or his children. The family would never sail aboard the Phoenix together again.

But the Phoenix’s adventures were hardly over. As the Reynoldses were splitting, the boat was on the verge of becoming an international symbol for peace.

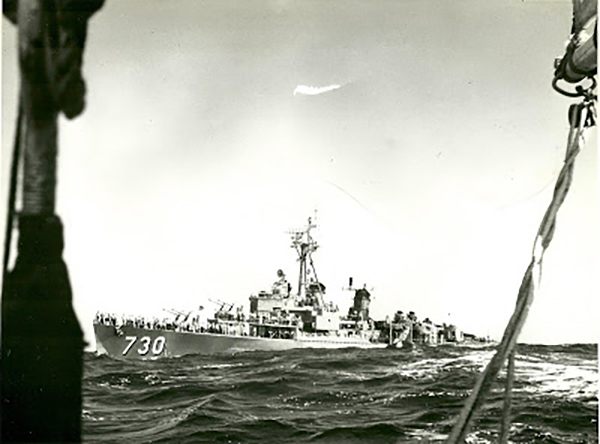

An Honorary Crew Member card that Reynolds and his family had printed and sent to supporters.

By 1967, the United States had nearly 200,000 troops in Vietnam. Quakers around the world had condemned the conflict and feared it could lead to hundreds of thousands of deaths. A rebellious new organization called A Quaker Action Group, or AQAG, believed taking direct action—dangerous and illegal protest in Vietnam itself—was the only way to stop the war.

Most Quaker groups were service-oriented and law-abiding. They provided medical care or lobbied the government. But service groups were already delivering aid in Vietnam’s American-supported South, and AQAG wanted to sail medical supplies into North Vietnam.

When Earle was in Hawaii fighting the charges against him, he began attending Quaker meetings and eventually converted. In 1966, one of the founders of AQAG, who had been on the Golden Rule in Hawaii, reached out to him: They wanted to use the Phoenix to sail into Vietnam. Earle agreed.

George Lakey, a founding AQAG member, thought sailing to Vietnam was “a drippy, corny idea,” but he didn’t have a better suggestion. He was “not a boat person,” and seeing the Phoenix for the first time didn’t change his mind. He shakes his head remembering the yacht. “It was so sloppy and tiny.”

Phoenix in Hong Kong harbor, en route to North Vietnam, 1967.

AQAG faced opposition from the United States government (who froze its bank accounts, stopped accepting packages for the organization, revoked members’ passports, and threatened 10-year prison sentences under the 1917 Trading With the Enemy Act), the North Vietnamese (who refused to grant them visas), and other Quakers (who felt an illegal voyage would erode support for the organization’s more established service efforts).

The idea of bringing medical supplies to North Vietnam on a boat, against the wishes of the U.S. government and in the path of the Navy’s Seventh Fleet, was controversial. “I never felt it was flippant,” Lakey says. “I just thought it was warranted under the circumstances. I saw no chance of getting the U.S. out of the Vietnam War unless we were forced out.”

The crew launched on March 22, 1967. During the five-day journey, “hearts were in people’s mouths,” says Lakey, who followed the voyage’s progress from afar. “It wasn’t a great chance for reevaluation of the Vietnam War; it was, ‘Oh my God, these people are going to die.’ ”

Tension on board was heavy. Earle, who served as captain, wanted to carry a gun, despite it being against Quaker beliefs. He barked orders and was impatient with the group’s insistence on making decisions through consensus.

“On a boat you obey the skipper. It is not a democracy. It’s not a Quaker meeting,” Jessica explains. Earle was autocratic and irritable, and the Quaker crew did not cherish his beloved boat. “This was the first time in my 13 years of association with the Phoenix that there were on board people who disliked her, to whom the boat was a necessary evil,” Earle wrote in a letter to AQAG leadership. The Phoenix and her crew spent five days seasick as they traveled from Hong Kong to the city of Haiphong.

While they waited in the Gulf of Tonkin to dock, the harbor went dark. Someone shouted, “Air raid!” and flames streaked across the sky. The activists watched in horror as five surface-to-air missiles crawled overhead. The Phoenix shook as the bombs exploded. They were told an American plane had been shot down.

Reynolds’ book The Forbidden Voyage of the Phoenix into the A.E.C prohibited zone.

Ten minutes later, the North Vietnamese navy piloted the boat down the river to Haiphong. For the next two weeks, the Quakers, always accompanied by the North Vietnamese, attended banquets, met patients in hospitals, and visited bombed villages. Earle tried to stay on the boat. According to Jessica, he felt it was a “huge propaganda ploy that made the crew of the Phoenix seem extremely anti-American.” He declined to go on another trip, but he continued to loan his boat to the Quakers.

The press covered all of it. Like the Reynolds’ trip to the nuclear test zone, the public and media response to the voyage was mixed. Those opposed to the war applauded the Quaker efforts to aid civilians and raise awareness. Those who supported the U.S. intervention claimed the protests were aiding the enemy and putting U.S. soldiers’ lives in danger. But Lakey and the rest of AQAG considered the trip a success.

When the Quaker group tried to arrange a second trip to Haiphong, the North Vietnamese asked the Phoenix not to return. The group decided to deliver medical supplies to the South Vietnamese city of Da Nang, demonstrating they weren’t taking sides.

Lakey, who says that God called on him to make the second voyage, was miserable during the trip. Seams had opened and the cabin “was like crawling into a wet sponge,” he says. The crew arrived in Da Nang on November 19, 1967, but the South Vietnamese would not let them dock because they were also bringing medicine to the Unified Buddhists.

A standoff ensued. The Quakers refused to leave without delivering their medical aid, so the South Vietnamese tried to tow the Phoenix out of Da Nang Harbor. The crew had spent hours deciding what to do if this happened. With the floodlights of gunboats illuminating the yacht, Lakey and Harrison Butterworth, an English literature professor, jumped into the water.

Butterworth “took off swimming like Tarzan in a movie,” captain Bob Eaton says. Onshore, he got a face-to-face meeting with a Vietnamese general, but the answer was still “no.” They kept trying. At one point, the Vietnamese set up a fire line: If the Phoenix crossed, they’d be shot. They sailed through it anyway.

“We called their bluff,” says Eaton, his voice cracking, nearly 50 years later. “If we’d all been shot, I guess people would have said how brave we were, or how stupid. But we were stupefied. It didn’t calculate as a threat.”

Still, the crew was unsuccessful. They took the supplies to Hong Kong and sent them to the Unified Buddhists via freighter. In January 1968, the Phoenix made a final trip to North Vietnam, but officials cut the visit short. The Viet Cong had launched the Tet Offensive and expected the South Vietnamese or Americans to “bomb the port to ashes” in retaliation, Eaton says. “We didn’t want to add to the confusion having to protect us. We left with a very heavy heart.”

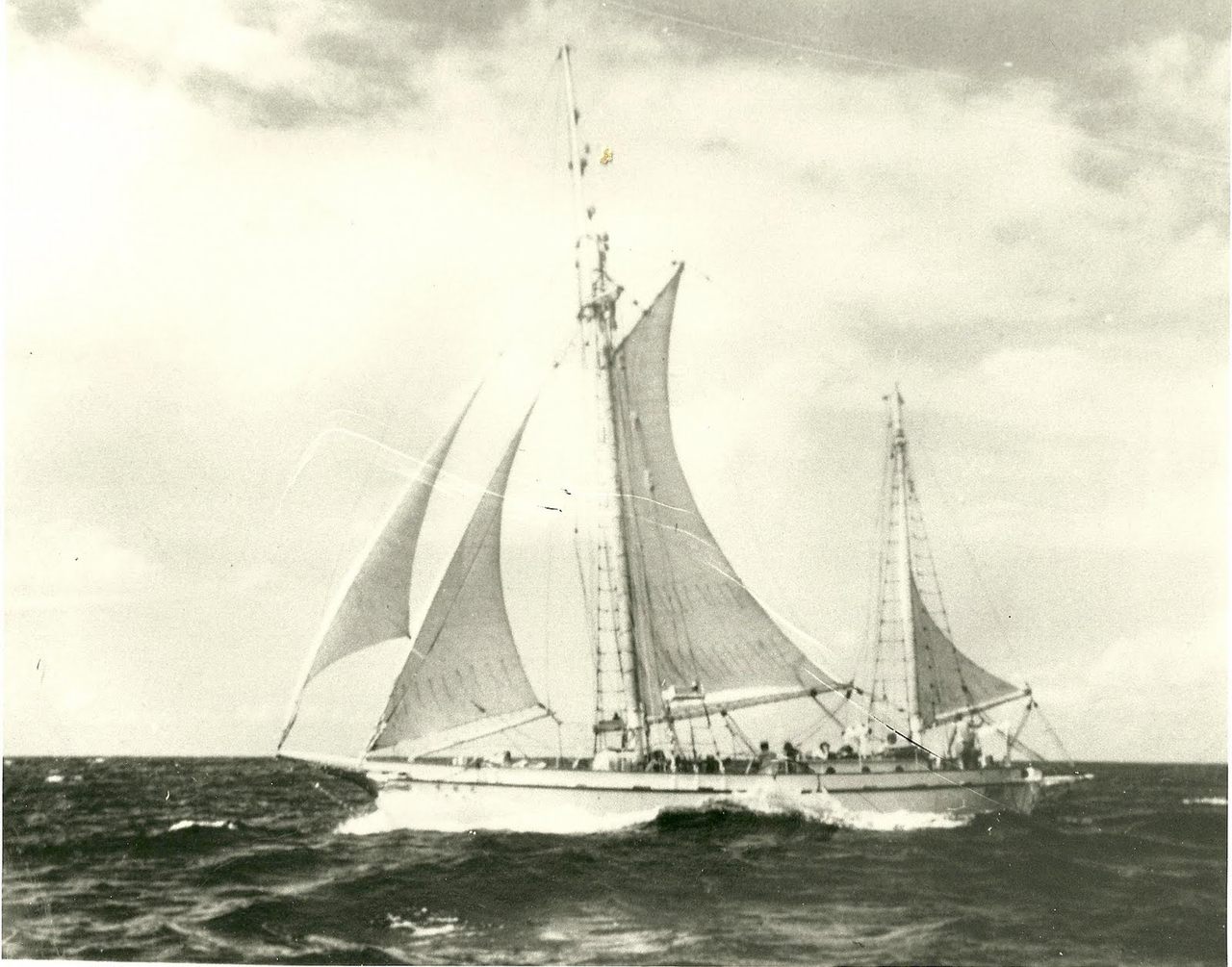

The Phoenix at sail.

The natural inclination of every boat everywhere is to sink. Every vessel that is floating is floating because of the work, time, and money someone—usually many someones—invested to keep it from going under. It’s here that the Phoenix began its most harrowing journey.

After the Vietnam War, the Phoenix was returned to Earle, who twice attempted to sail it to China. He envisioned a goodwill voyage of “friendship and reconciliation,” since Japan and China had no diplomatic relations. Neither nation was interested. The Phoenix was forced to turn around 20 miles from China, and when Earle returned home to Japan, the government kicked him out of his adopted country.

Earle took the Phoenix across the Pacific Ocean a final time and sold it to a man named Tomas Daly for $20,000. Daly, who is now 75, was in awe of Earle. On the phone from his home in Mexico he compared Earle—favorably—to Bernie Sanders and Edward Snowden. He too wanted to circumnavigate the world in the Phoenix, but after pulling tons of pig iron out of the bilge, stripping the wood, and repairing the dry rot, he realized it was never going to work. In 1977, Daly sold the Phoenix to a man named Norman Sullivan for $10,000.

By 1990, the boat was up for sale again. It had fallen into disrepair, but Al Hugon bought it, unaware of its past. He owned the ship for nearly 20 years, sometimes living on it, but his printing business struggled, and by 2007, he could no longer afford the upkeep or fees.

“You have to live on it,” Hugon says. “You can’t even just go down to clean and work on it on a Saturday or Sunday. You have to keep the engine and the gearbox running, the bilge pumps working. You have to haul it out of water every two, three years.” He tried to get surviving members of the Reynolds family to take it. He approached Greenpeace and some museums. When no one had the money or will to fix it, he put the Phoenix on Craigslist for free.

John Gardner, a 31-year-old recovering meth addict with no money or sailing experience, saw the ad. He knew the boat’s history and imagined “helping humanity,” specifically teenage gang members. He took it. “I just want to save this historical boat and save some kids. I want to put them in uniform and sail them around the world,” he told the Stockton Record.

As Gardner lugged the Phoenix out of San Francisco Bay, the boat ran aground twice. Then, as he towed it up the north fork of the Mokelumne River in Northern California, the boat hit a dock. Water rushed in. Gardner bought a solar panel to power a bilge pump, but someone stole it and, days later, he tried to pump the vessel manually. By then, the Phoenix was more submarine than sailboat.

Just off an overgrown island, the Phoenix—a civilian boat that had sailed around the world, been designated a national shrine in Japan, traveled to two nuclear testing zones, and made three wartime trips to Vietnam—now rests in muck, 25 feet underwater.

Last year, a group of volunteers finished a five-year restoration of the Golden Rule. Some of the people involved in that restoration have turned their attention to the Phoenix. Donations are trickling in. One person even pledged $25,000 to raise the boat if the Reynolds family can form a nonprofit for its restoration. In July, a local sheriff located the boat and took a sonogram. A diver examined it more closely and told the family that “every minute it’s down there, it’s deteriorating,” says Jessica. Getting it out of the water will be “just like a baby being born. As soon as it’s out there are going to be people there to wrap it, cuddle it, get it to [a salvage company in] Washington.” The whole restoration could cost $750,000.

The task of forming a nonprofit and raising money for the restoration has fallen to Naomi Reynolds, Earle’s granddaughter, who lives an hour and a half from the boat’s resting place. She wants to save the boat because it’s a family relic that represents something bigger—“that intersection of a major historical thing with a normal American family: mom and dad and 2.5 kids and the white picket fence,” she says. However, by her own description, she is “not an extroverted person,” and she worries she can’t generate enthusiasm for the project.

Others are hopeful. Eaton, who captained the Phoenix’s second and third trips to Vietnam, says that when people first started talking about restoring the Golden Rule, he was skeptical. It wasn’t until he saw the ship sailing again that he realized its value. “I don’t buy into relics in a church sense, for worship, but in fact they are important. They us tell us who we were; therefore who were are; therefore who we might be,” he says. “The question about bringing the Phoenix back is whether there’s a community of people who can breathe life into it.” After all, if there’s anything a phoenix is good at, it’s rising back to life.

This story was co-produced with Mental Floss. A version of this appears in their latest (and last!) issue.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook