The Most Precious Cargo for Lighthouses Across America was a Traveling Library

A postcard showing Gay Head Lighthouse, Martha’s Vineyard. (Photo: Boston Public Library/flickr)

From the vantage point of a 19th century lighthouse, a small, slow ship would appear every few months on the horizon. A woman, her husband and their children might look out at the glistening sea in anticipation from their tower: the shipment was finally here. They’d haul supplies from the boat; cleaning rags, paint, milk, and possibly the most awaited item: a thick wooden carrying case with brass hinges, filled with books.

Portable lighthouse libraries, distributed across the United States in the 19th century, were a common but important part of life for families living under the constant work and near-isolation of the lighthouse watch.

The life of a lighthouse keeper sharply vacillated between dullness and danger. “You know what they say about pilots—hours of boredom punctuated by moments of sheer terror? There’s something to that,” says Bonnie Stacy, chief curator at the Martha’s Vineyard Museum, which leads tours through local lighthouses and holds extensive records of historic lighthouse life.

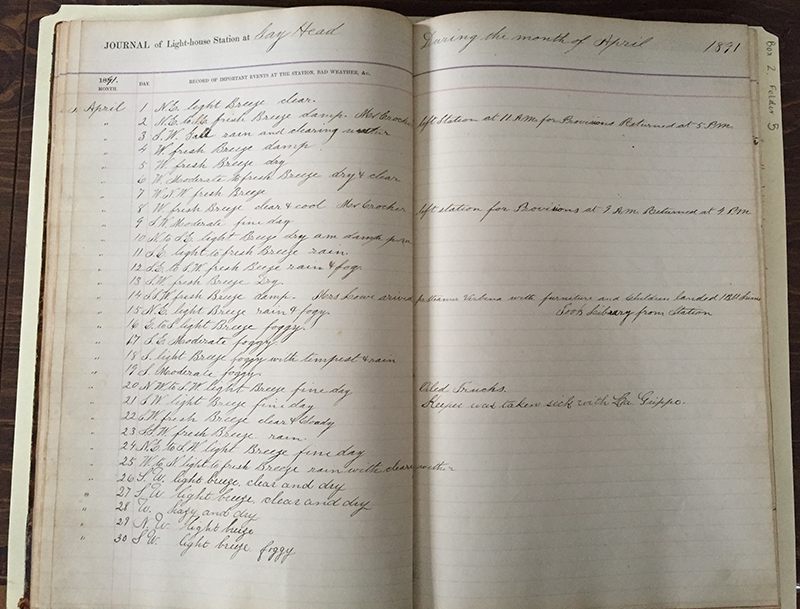

Keepers and their spouses worked and recorded events 24/7, through holidays and weekends, dutifully maintaining the important beacon of the lighthouse, which was often in a remote area. The official lighthouse log books that Stacy has sifted through contain everything from mundane notes on the weather (“light breeze, foggy”) to the tragic deaths of family members from scarlet fever, and mentions of any time a book was taken from the lighthouse.

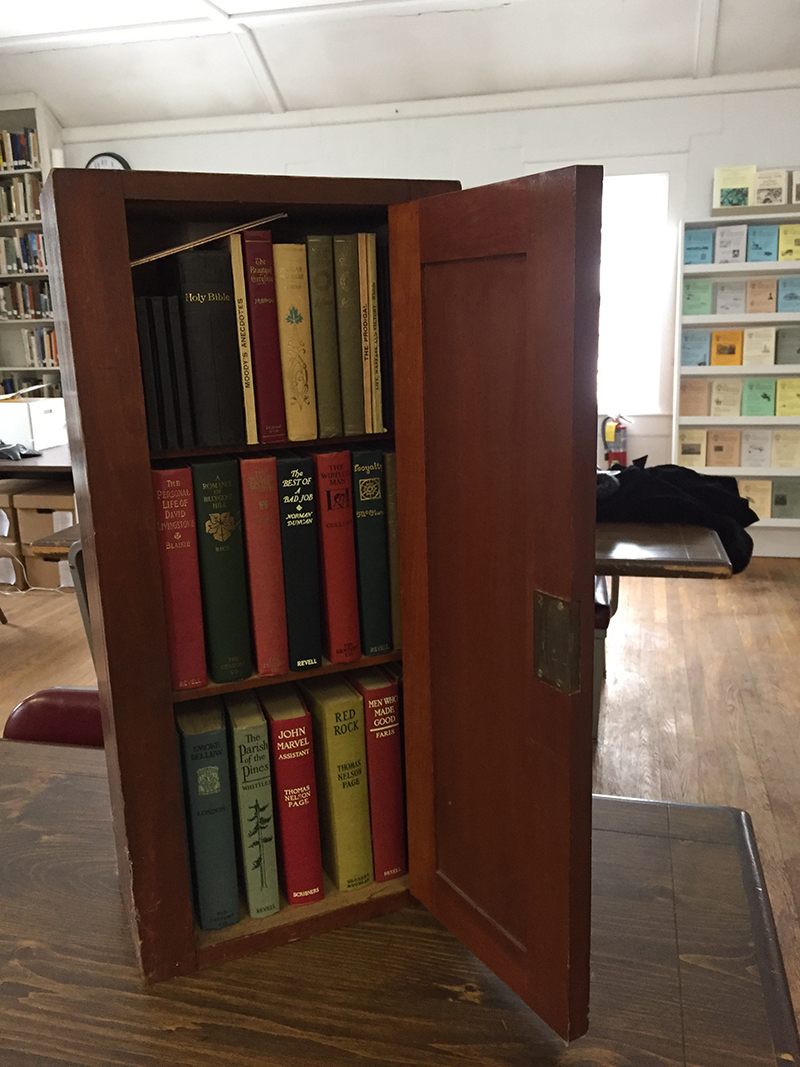

A portable library from the Seaman’s Bethel containing books from the American Seamen’s Friend Society, found from the wreckage of a schooner that sank in 1914, similar to libraries circulated among lighthouses (Photo: Bonnie Sandy/Martha’s Vineyard Museum)

As with everything at the lighthouse, keeping these books in good condition was serious business. Arnold B, Johnson writes in his 1885 article Lighthouse Libraries that each book case had a list of the case’s contents on the inside door; retrieving a book from the mini library entailed recording your name and the date you removed a book from the case, which was “examined by the Lighthouse Inspector on his quarterly round, and its condition is reported.”

Any lost or “injured” book had to be replaced, not least of all because of how many people lived in these lighthouses; children were often born in the lighthouse, growing up beneath its far-flung glow. “There are now about 350 such libraries in use, and as each lighthouse has an average of five readers,” writes Johnson somberly, “…it can be readily seen how many people are affected.”

Johnson writes that “a library may start from the light-station at Eastport, Me., and work its way clear round the coast, stopping at every large lighthouse in every Atlantic and Gulf State to the Mexican frontier; then, after visiting every large lighthouse on the Lakes, finally makes a tour of the lights on the Pacific coast.“

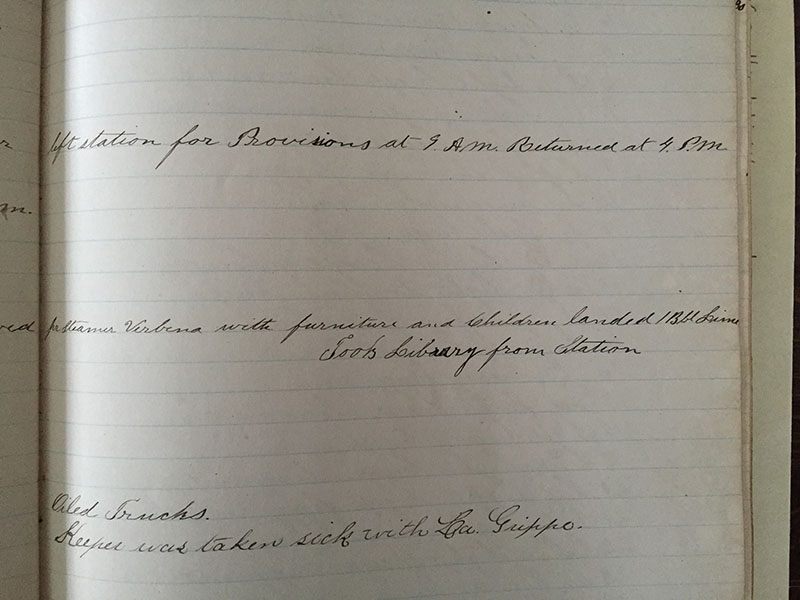

Logbook from the Gay Head lighthouse on Martha’s Vineyard, where each item, weather report and trip away from the lighthouse watch was recorded. (Photo: Bonnie Sandy/Martha’s Vineyard Museum)

As keepers and their families were always waiting and watching for something to happen, these libraries gave their minds some reprieve from the monotony. Days at the lighthouse were spent with maintenance: constantly re-painting wood against the rough sea air, cleaning the glass lens that protected the all-important light. But lighthouse keepers were also in charge of countless lives on a daily basis; they lent the only marker for ships in the night to check their location against the shadows and the stars. Before the advent of wired communication, lighthouse keepers were often the first witnesses to accidents at sea.

“You’ll see records, like when the [boat called] the City of Columbus wrecked at 1 in the morning, but [officials] didn’t know about it until the Gayhead lighthouse keeper saw it,” says Stacy. “In Aquinnah there was a rocky ledge called Devil’s Bridge that was dangerous, and that’s one of the reasons there was a lighthouse there.”

And while some degree of honor was conferred on a lighthouse keeper—he was often appointed by local seafaring officials—at the time a keeper earned roughly $200 a year on top of free living arrangements, according to Ray Jones in The Lighthouse Encyclopedia: The Definitive Reference, about $3,126 today. It wasn’t much to live on, especially with a family.

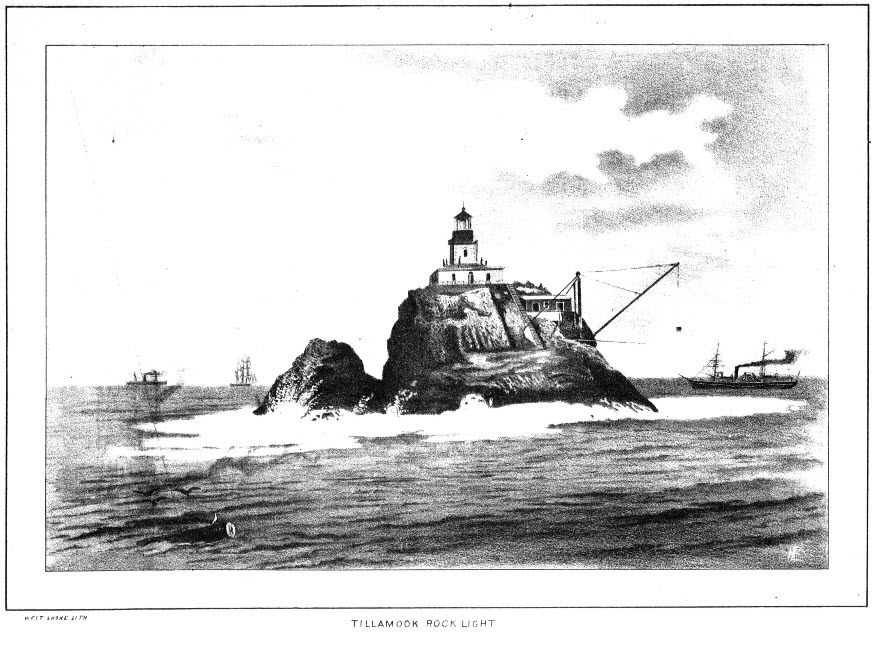

Tillamook lighthouse in Oregon, illustrated in 1883. (Photo: Washington State Library/flickr)

Tillamook lighthouse in Oregon, illustrated in 1883. (Photo: Washington State Library/flickr)

All this meant that lighthouses and their keepers needed to be kept in the best possible shape. Starting in the mid 19th century, the United States Lighthouse Board, which dissolved into the U.S. Coast Guard in 1939, began making positive changes for lighthouses around the U.S.; new fresnel lenses were fitted over towers’ gas lights, which projected the signal over larger distances; fresh paint was issued to protect lighthouse wood and to mark one tower from the next. And of course, there were amusements to keep the loyal lighthouse keeper sane, most notably the traveling libraries that arrived around 1876.

District inspectors, who oversaw the lighthouses and their supply stores, would swap a lighthouse’s library with that of his maintenance ship on a quarterly bases, coordinating which library went to whom. Once it made its rounds in one district, inspectors passed the libraries amongst themselves, and in this way the library traveled the entire circuit of lighthouses in the country.

In his 1885 article, Johnson goes on to explain that inspectors probably began the lighthouse library practice, seeing that lighthouse keepers “seized on any reading matter that came in their way”; books and magazines were informally passed around until the United States Lighthouse Board bought bookcases, to be filled with books purchased or donated by private groups.

A close-up of the log book, which reads “took library from station”, a reference to the inspector removing one library to be exchanged for another. (Photo: Bonnie Sandy/Martha’s Vineyard Museum)

These libraries may have had a bit of an agenda to promote Christian values, writes William Waterway, in GayHead Light House, the First Light on Martha’s Vineyard. Many of the books were distributed by the American Seamen’s Friend Society, a religious group based in New York which placed great importance on combatting the coarse reputations of sailors.

Existing portable library programs had existed for merchant and navy ships for decades (and still do, through the Navy General Library Program). In 1865 The New York Times reported that the American Seamen’s Friend Society had dispersed 1,369 library cases since 1859 to naval vessels, occupying the minds of 20,000 officers.

Bringing God to the sailors was seen as the ultimate good for a man out at sea, who might fall prey to wayward tendencies.The article adds that “they will push this work till the 25,000 American vessels are supplied with them and our sailors have the privileges on the ocean of the Sabbath School children at home.”

By 1876, the American Seamen’s Friend Society, in concert with the United States Lighthouse Board, began working to bring books to the Navy’s land-bound allies–the lighthouse keepers.

There were at least 420 libraries circulating for lighthouses in the United States by 1885, which might have rivaled the readership for most other citizens. Waterway writes that, “In the late 1800s, there were more lighthouses than libraries in America, thus giving an assist to educating lighthouse books.”

An etching from 1879 of a lighthouse by night. (Photo: New York Public Library)

The library boxes were made from thick, heavy wood, and needed to do double-duty as carrying cases and bookshelves. “Let it be shut, locked, and laid on its back, and it is a brass- bound packing-case, with hinged handles by which it may be lifted; stand it on a table and open its doors, and it becomes a neat little book case,” Johnson writes. A library box could hold 50 to 60 books.

The contents of the libraries themselves seem to be as varied as their locations. The Michigan Lighthouse Conservancy website gives an example of its own portable lighthouse library, with books marked ‘Property of the Lighthouse Establishment.’ Works of fiction were the focus there, including James Lamont’s Seasons with the Sea-horses; Or, Sporting Adventures in the Northern Seas, and part of a series of six Swedish romance novels called The Surgeon’s Stories–Times of Charles XII.

Inside a library salvaged from a schooner which sank off Martha’s Vineyard in 1919, books range from Moody’s Anecdotes to The Best of a Bad Job by Norman Duncan, and a nonfiction book about radio transmissions called The Wireless Man, to a mysterious medieval German title. There’s also a Bible and a hymn book linked to the Seaman’s Bethel, a religious group for those who lived at sea. “The Seamen’s Bethel- their job was religion, and administering to sailors. I’m sure that the books were carefully chosen to be wholesome,” says Stacy.

A woodcut showing Boston Light, 1895. It was the last manned lighthouse to switch to an automated, electronic light, in 1998. (Photo: Library of Congress)

Today, there’s no one left to read Swedish love stories in the afternoon light of a lighthouse parlor room in the United States—lighthouses are now automated. The last manned lighthouse, the Boston Light, switched to electronic light in 1998, and the last civilian lighthouse keeper in the United States passed away in 2003. In some parts of the world, like Germany, lighthouses are being done away with altogether–GPS systems make them arguably redundant.

Lighthouses in the U.S. are still key to navigation, though, and laws like the Lighthouse Preservation Act allow the structures to continue decorating outlying rocks and coasts. Beside a few museums here and there, libraries aren’t found in lighthouses anymore. The people who take care of historic lighthouses on a day-to-day basis are museum workers or tour guides.

Of course, even if lighthouses were still manned by keepers, it’s likely that e-readers would be the more popular and convenient choice for getting books to remote areas now; the romantic libraries would probably still live in the past. But for more than a century, this ingenious method of passing books from lighthouse to lighthouse, and from ship to ship, helped keep men and women living in remote areas buffeted by the elements to feel some semblance of connection with the rest of the world.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook