A Vast, 430-Year-Old World Map, Full of Places and Creatures, Real and Imagined

More than 60 square feet of cartographic wonder.

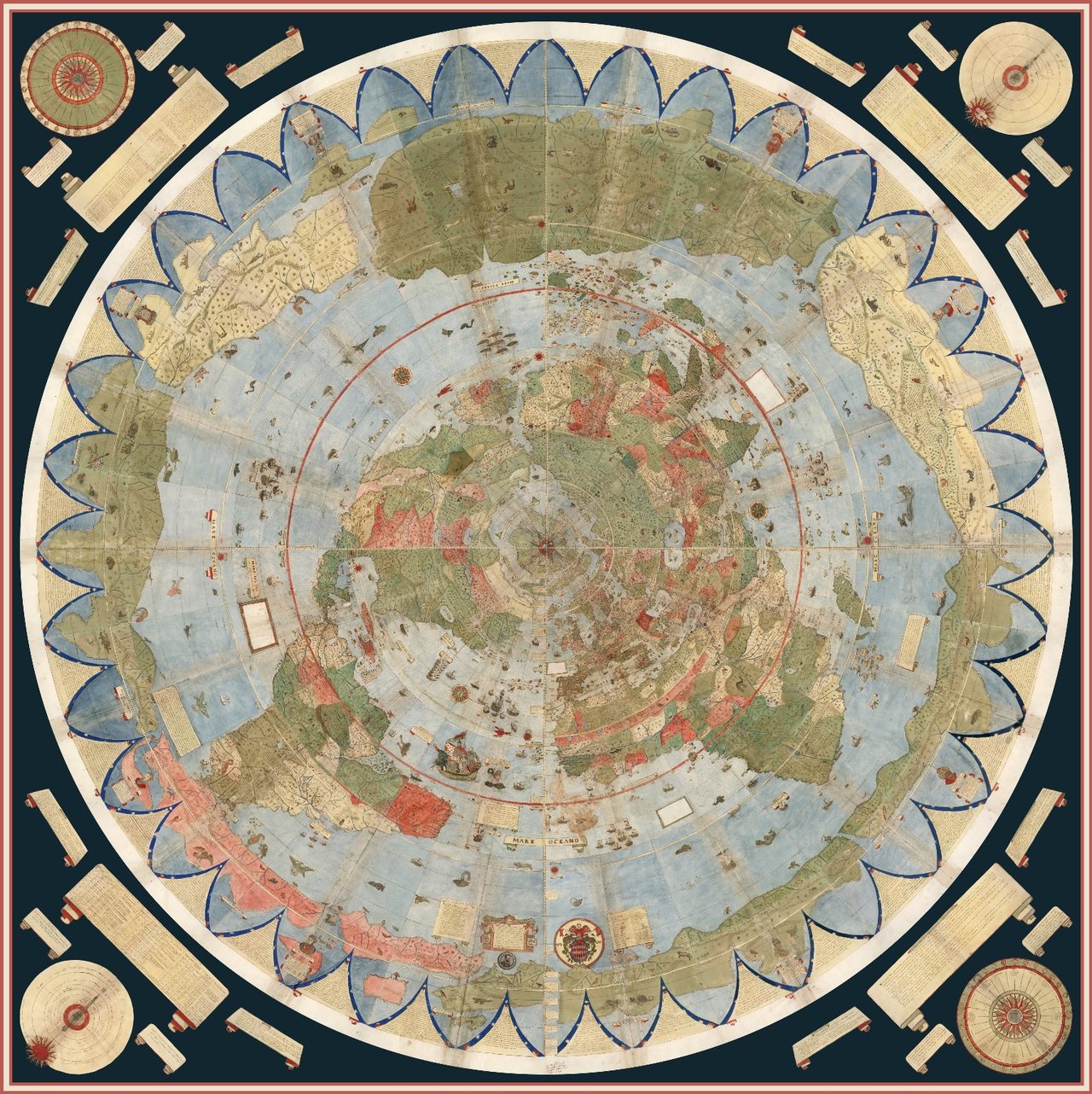

Born near Milan in 1544, Urbano Monte lived a life of leisure and luxury. For him, such freedom meant scholarship, and the accumulation of a library renowned in the region. In his early 40s, his interests turned to geography, and a mammoth 20-year effort to synthesize and consolidate everything known of the world’s geography into a few volumes. More than that, he wanted to make a planisphere map of the world “to show the entire earth as close as possible to a three-dimensional sphere using a two-dimensional surface,” writes map collector and scholar David Rumsey, who digitized the maps shown here.

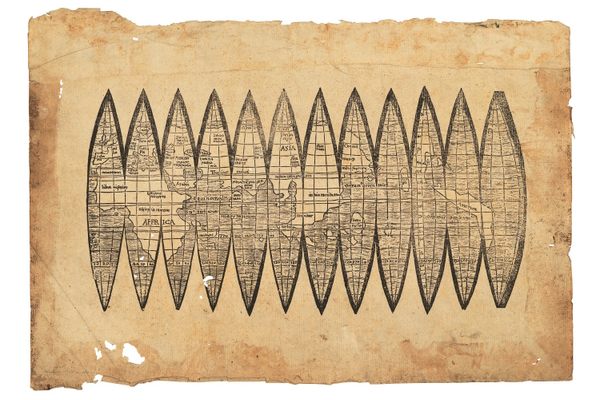

Monte envisaged the component maps—60 in all—being stitched together, and so left detailed instructions for how to turn them into one giant representation of the world, over nine feet in diameter. Included in the four volumes are also charts showing the lengths of days at different times of year and an extended geographical treatise on the world and cosmology. Unlike many modern maps, which use the Mercator projection from around the same time, his map shows the world from directly above the North Pole. Today, this perspective is known as the north polar azimuthal projection, most famously used on the logo of the United Nations.

Once assembled, the map shows a lush, highly personalized take on the world, with a surprisingly large collection of real and fantasy beasts carousing and cavorting on land and sea. Rumsey’s scan and digital assembly of the cartographic puzzle represents the first time that Monte’s work has been seen in its full glory: It is the single largest world map of the 16th century, and one largely forgotten or overlooked by cartographers and scholars.

Monte did not come by his geographical knowledge by traveling the world. Rather, most of the map is sourced from others already floating around, and long texts describing the journeys of early voyagers, so it pulls in their various misconceptions about far-flung places, particularly around South America. It’s hoped that more study will reveal precisely which texts he drew from. His Japan, on the other hand, was the product of sustained individual study and conversation with visitors from Japan from the 1580s. While it bears no real resemblance to any modern map (and seems to be the wrong way up), the level of detail is impressive.

Throughout the world, Monte took time to sketch exotic fauna—crocodiles, camels, lions, and more. Near a coast labeled “Terra Incognita” (somewhere around Alaska), a wolf with a cub looks watchfully over its shoulder. Elsewhere there are more fantastic beasts, including griffins and what looks like a huge bird clutching an elephant. The seas feature many-tailed mermen and fleets of well-armed ships. Political leaders, including Philip II of Spain, also make an appearance, as do several portraits of Monte himself. Mapmakers of the time didn’t like empty spaces, Rumsey told CBC Radio. “There were many places that they did not know the names of towns and locations, so they filled them up with trees, monsters,” he said. “They just used it as a palette, and it’s so artistic and interesting that it just, it grabs us today.”

Monte would likely be excited to learn that his little-viewed map is finally getting the audience it deserves. At Stanford University, members of the public can see the manuscript itself, still vividly colored, a full-scale reproduction from the scans, and an interactive digital version of it. It is also available to explore online. In the meantime, researchers are looking closer at this rare masterpiece and the treasures it holds.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook