‘Sacred Harp’ Singing Treats Every Human Voice as Holy

In the rural American South, these non-denominational sing-alongs are part of a long musical tradition.

At Sacred Harp singings, the country churches of the American South resound with the harmonious pulse of song. There are no instruments, just human voices carrying on in four-part, a cappella harmony. Loud and hypnotic, it doesn’t sound like a traditional, melodious sing-a-long. Rather, it’s like a swell of voices chanting with such raw emotion, it sounds as if the room might burst.

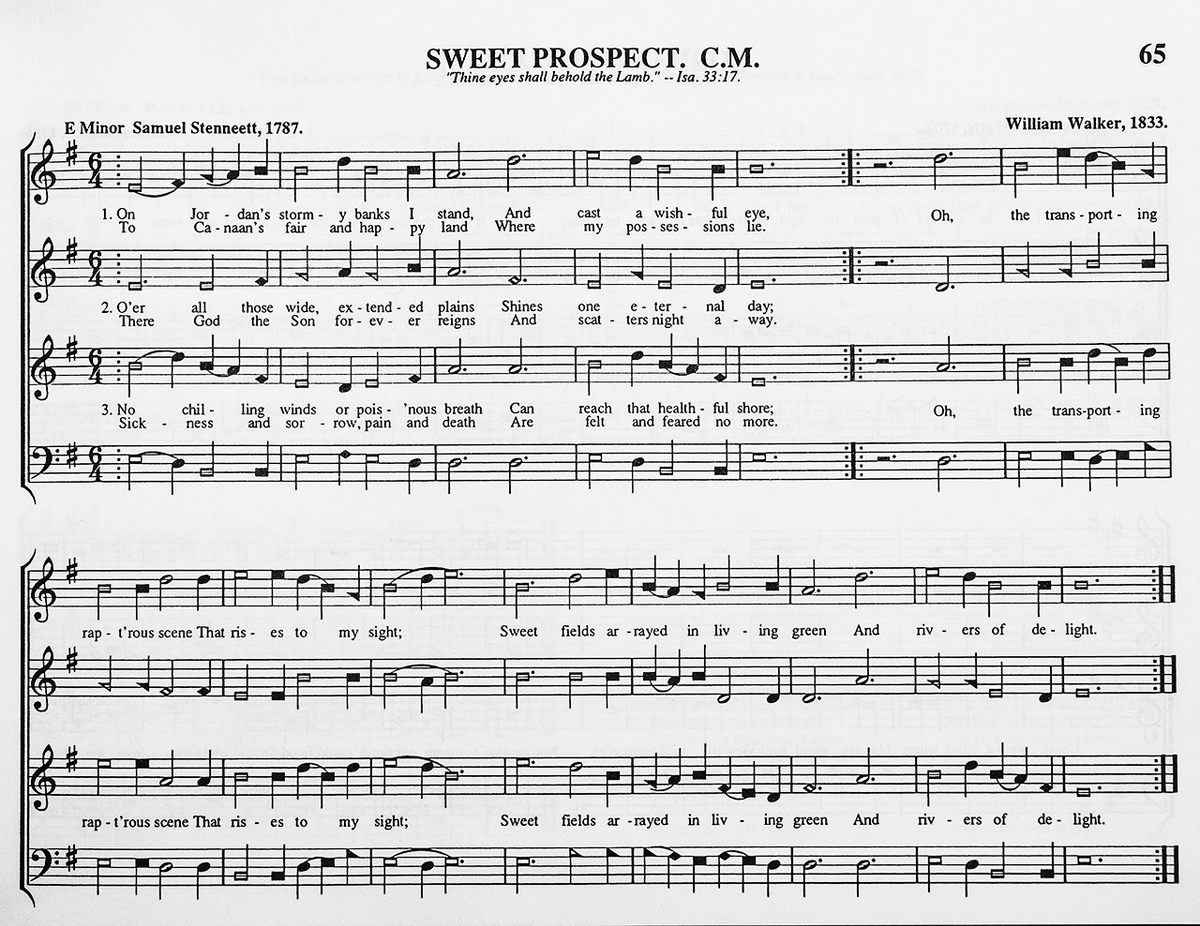

In this style of music, the tenor, alto, and bass are independent of the melody. With the four parts so distinct, they’re printed on separate staves. This dispersed harmony creates an unusual blend of voices, giving Sacred Harp its signature sound.

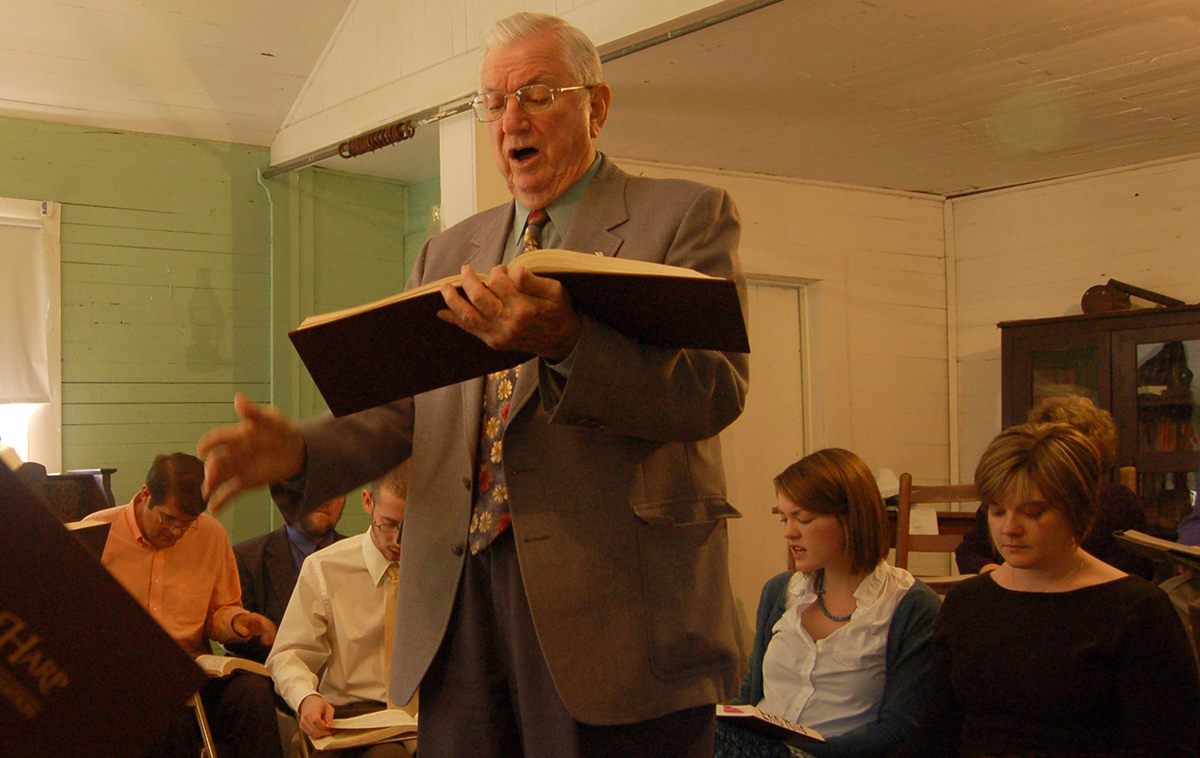

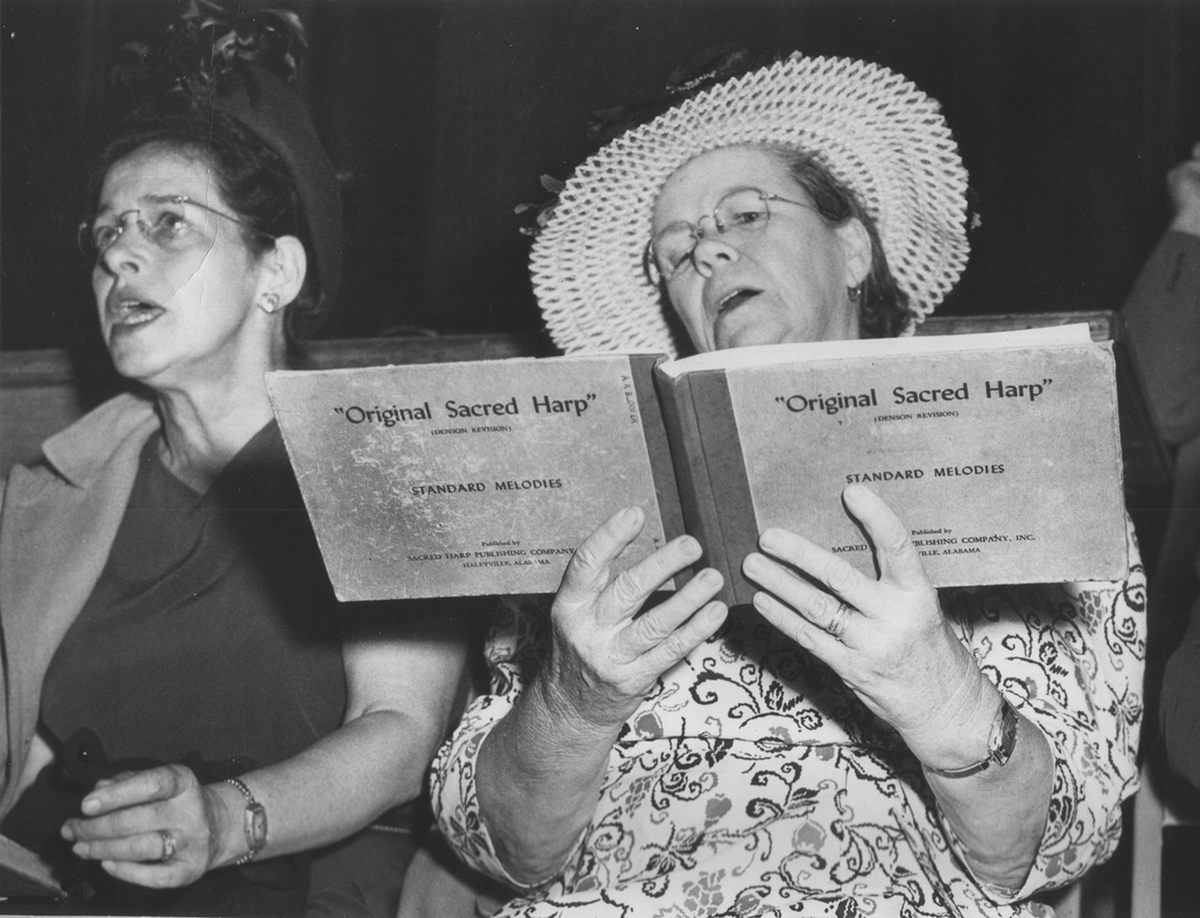

During a singing, vocalists, arranged around a central square, hold their oblong songbooks so they can easily shift their eyes between the pages and the person leading the song. The leader, in the center of what is known as the “hollow square,” balances the same book in one hand while the other hand, open-palmed, steadily beats the rhythm like a metronome. Some singers mimic this motion with their own hands. Rows of wooden pews creak as the participants rock back and forth, their feet thumping against the floor.

Sacred Harp singing is an outgrowth of a form of musical notation known as shape notes. According to the president of the Sacred Harp Musical Heritage Association and lifelong Sacred Harp singer David Ivey, shape-note music was often the first, or only, form of musical training many rural Southerners had well into the 19th and 20th centuries. (Disclosure: Ivey is the author’s cousin.)

Shape-note singing took root during the 18th century when itinerant singing instructors began offering lessons to communities around New England. These singing schools taught the practice of solfege—associating each musical tone with a different syllable.

However, rather than the traditional seven-note singing scale (do, re, mi, fa, sol, la, ti), in Sacred Harp the note-heads are printed as four different shapes bound to four syllables: fa for triangle, sol for oval, la for rectangle, and mi for diamond.

Instructors taught their students to “sing the shapes” before singing the written words. This system was designed to teach an effective form of sight-reading to those with no access to conventional musical education.

Eventually in the Northeastern U.S., where more structured European musical norms prevailed, shape-note singing became regarded as unsophisticated and old-fashioned. These singing schools needed a new home, so teachers migrated south.

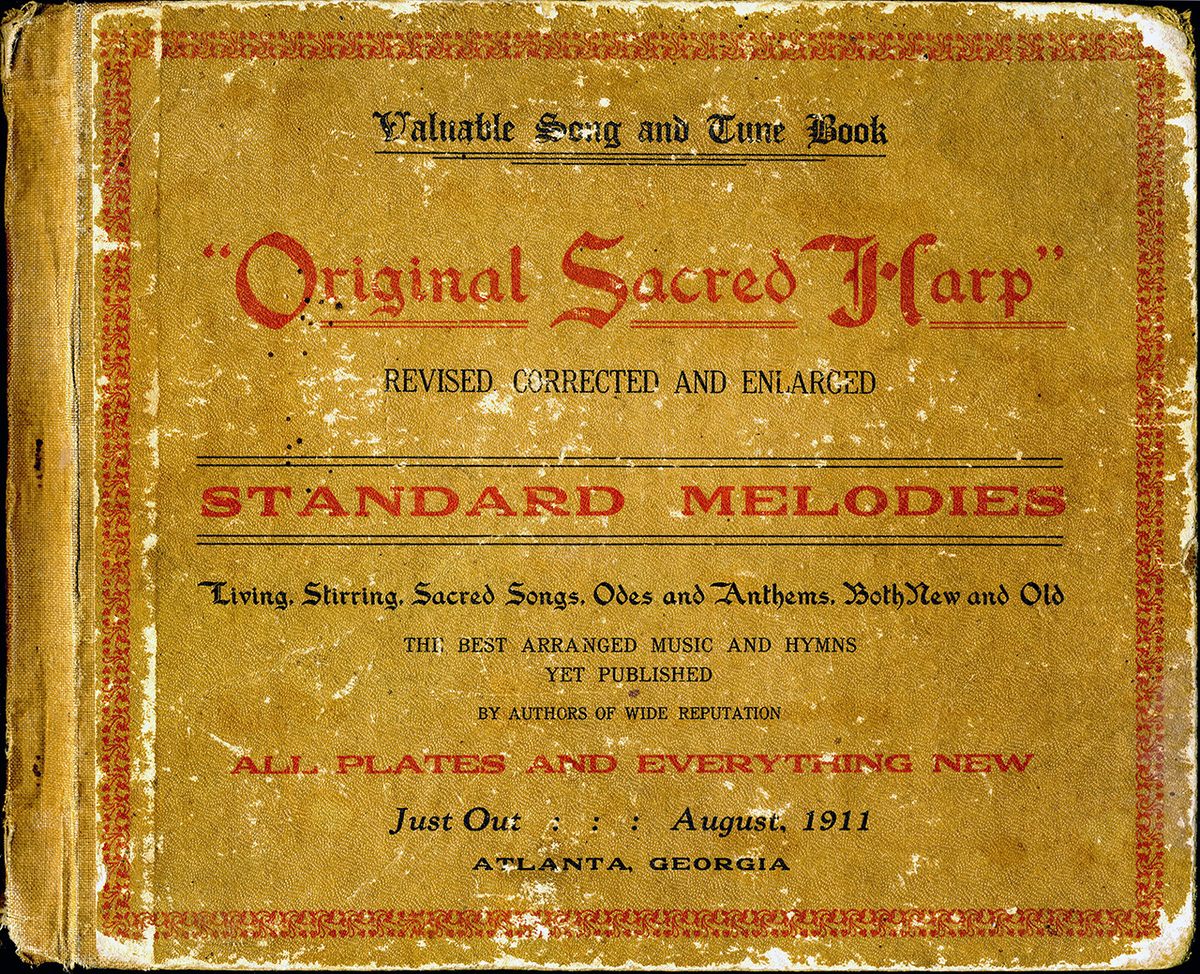

Around this time, in the early 19th century, two important shape-note books were published by brothers-in-law from South Carolina: Southern Harmony in 1835, by William Walker, and The Sacred Harp in 1844, by B.F. White. The latter branded the name of this musical style “Sacred Harp,” in reference to the human voice. Influenced by 18th-century English church music, these songbooks were composed of hymns, anthems, and fuguing tunes, as well as 19th-century Southern hymns stemming from British and Irish folk songs.

Southern Harmony and The Sacred Harp helped promote shape-note singing in rural parts of the South, where it began to firmly root in what would become its permanent home. Both songbooks remain prominent in the shape-note singing community today, with The Sacred Harp having undergone numerous revisions to keep up-to-date with newly composed songs.

For many Sacred Harp songs, the words and the tune were not composed together. A common practice was to select a hymn with lyrics that metrically fit the melody. For example, sources have connected the meter of the hymn “Wondrous Love” with the 1701 English pirate song “The Ballad of Captain Kidd.” While the lyrical origins of “Wondrous Love” remain unknown, the first time the song’s words and folk tune were published together was in William Walker’s second edition of Southern Harmony.

Like many other Sacred Harp songs, “Wondrous Love” is full of spiritual elements, meditating on Jesus Christ bringing salvation to the world. Despite this, while many singers in the community observe shape-note singing religiously, Sacred Harp is and has always been inclusive and nondenominational. There is no sermon to accompany the singings.

“Sacred Harp brings together people with many differences,” Ivey says. “Those differences are erased as we sing to each other across the hollow square. Singing in a formation where you see all the others who are contributing to this glorious sound creates an instant bond.”

Another element in “Wondrous Love” that can be seen in many other Sacred Harp songs is its haunting minor key, and the celebration of what’s to come after death:

And when from death I’m free

I’ll sing on,

And when from death I’m free

I’ll sing and joyful be,

Thro’ out eternity, I’ll sing on

As evident by the lyrics of shape-note songs and the living traditions of both the Memorial Lesson and Decoration Day, openly discussing death is a common theme in Sacred Harp.

“The Memorial Lesson is a time of the singing in which we call the names of singers and friends who have died in the past year and sing songs of remembrance to them,” Ivey says.

Decoration Day, while also practiced by Southern United States and Liberian communities not associated with Sacred Harp, is an event during which family and friends gather to clean and decorate cemeteries, bridging a spiritual connection between present and past generations.

According to Ivey, at a Sacred Harp Decoration Day singing, four or five songs are sung in the cemetery at the first recess. Usually at all-day singings, including the ones that happen on Decoration Day, there’s “dinner on the grounds.”

“Having dinner on the ground—or as city people say, potluck—is an important time of the all-day singing,” Ivey says. “It’s an experience of sharing family recipes and stories that are as important as the singing itself.”

Shape-note singings are still held in the South today, primarily in Alabama, Georgia, Mississippi, and Texas. Just like in the early days of Sacred Harp, singers sit in a square with the four vocal parts on each side. The tenors, both men and women singing an octave apart, face the altos; the trebles—the highest-pitched part mixed between men and women—face the basses.

Keeping in line with tradition, singers sing the first verse as the shapes (fa, sol, la, mi) to lodge the tune in their memory before they sing the written words. The leader, a rotating role, stands in the middle of the square. That individual leads the song of their choice while keeping the others in rhythm by “beating time” with an open-palmed hand.

However, shape-note singing is not a performance—at least not in the same way as a recital or concert. “Sacred Harp is not about fitting some ideal of a pretty voice,” Ivey says. “It’s about the experience. There’s never any rehearsal. There’s no set of singers who definitely attend, so it’s nothing like a choir. People gather just before the start time with anticipation of what the sound of that day’s gathering will be. Then the pitch is given. The four parts ‘sound the chord’ and the singing begins.”

In the 2006 documentary Awake, My Soul: The Story of the Sacred Harp, Hugh McGraw describes the first time he experienced shape-note singing, in 1953: “I just walked in the back door and sat down on the back pew … And when I sat down and heard [the singing], it was like I had received salvation.” Regarded as one of the leading Sacred Harp singers of the past 50 years, McGraw was essential in spreading shape-note singing across the U.S. in the late 1970s and early ’80s. Today, Sacred Harp is now sung all over the country, as well as internationally.

Sinéad Hanrahan, who attends singings in Cork, Ireland, first encountered Sacred Harp as a performance module offered as part of her undergraduate degree. She has since traveled across Ireland, the United Kingdom, and continental Europe as a direct result of Sacred Harp, even working as a singing school teacher for an all-day singing event in Oslo, Norway.

“Our singings in Cork are pretty informal,” Hanrahan says. “To lead each song, we move around the square in turn. Everyone is welcome to lead a song, but it’s not obligatory. After the singing, all are welcome to join for a drink and a chat in our local pub.”

Both Hanrahan and Ivey agree that what pulls them to Sacred Harp is the community. “I can walk into a singing anywhere in the world and the familiarity of the space and the singing and the interactions means I immediately feel welcome,” says Hanrahan. “The realization that there is this community of people around the world, bound together by the shared love of this music, is quite a powerful thing.”

This community continues to keep shape-note singing alive and nourished. A testament to the important role music plays as an oral tradition, Sacred Harp connects the present and past and bonds singers with their heritage. It’s a bond that strengthens each time someone calls out a page number and sounds the chord—a bond between voices celebrating the shapes that taught the rural South to sing.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook