The Wool Brigades of World War I, When Knitting Was a Patriotic Duty

The clacking of needles was heard from coast to coast.

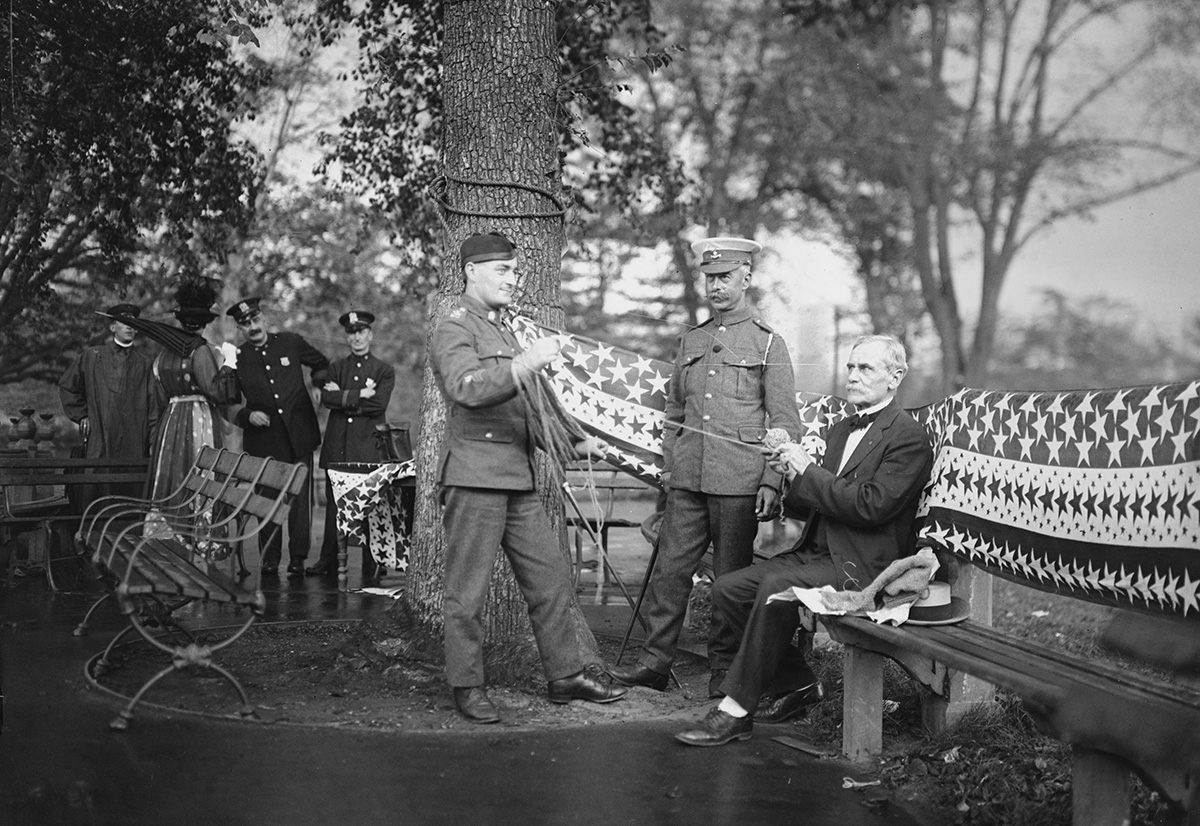

In August 1918, the Comforts Committee of the Navy League of the United States opened a three-day knitting bee in Central Park. It was a massive event, with a sole purpose: to produce warm garments for those fighting in World War I. At the event, there were knitting competitions for speed and agility, and attendees ranged from children to octogenarians. The numbers were so great that one of the chairwomen said, “the click of the needles could be heard all the way to Berlin.” By the end of the “knit-in,” the Comforts Committee had raised $4,000 (roughly $70,000 today) and created 50 sweaters, nearly as many mufflers, 224 pairs of socks, and 40 head-and-neck coverings called “wool helmets.”

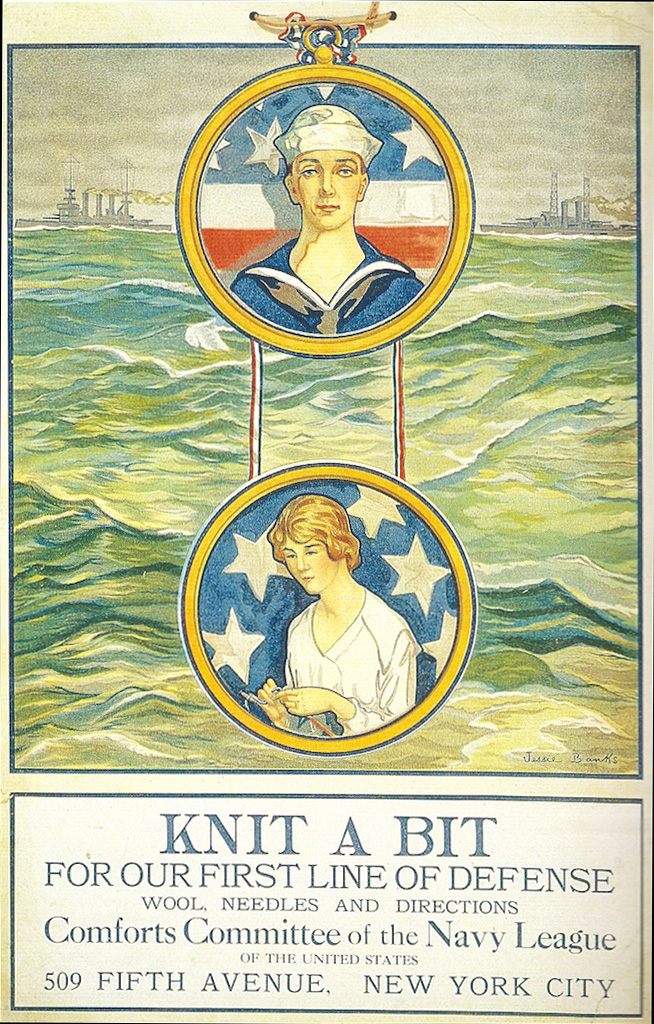

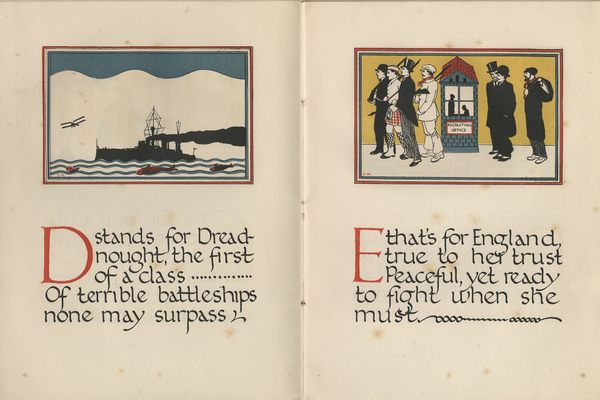

During the war, there was an overwhelming effort to assist those fighting abroad. Before America even joined the war, organizations such as the American Red Cross and the American Fund for the French Wounded had issued pleas for warm clothing for soldiers—or, as a Navy League poster put it, to “Knit a Bit.” After April 1917, the Red Cross and the Comforts Committee worked together to mobilize ever larger numbers of knitters, with a request for 1.5 million knitted garments. (There was also another way to use knitting against the enemy—spycraft.)

The need for warm clothes, particularly socks, was desperate. Men at the front were fighting in the atrocious conditions—muddy trenches and frigid winters—with inadequate footwear. “The difficulty is to keep one’s feet warm,” wrote one officer in 1917. “One walks and they get warm, stand for one minute and they are icicles again.” Soldiers also needed to keep their feet warm and dry to avoid frostbite and trench foot, and the best way to do this was to don clean socks regularly.

Knitting was promoted as a patriotic duty. A Red Cross poster showed a woman knitting diligently, with the words, “You Can Help.” Tape measures were sold in red, white, and blue, and the Betsy Ross Yarn Mills advertised their water-repellent, khaki and grey wool with “Uncle Sam Wants You To Knit To Protect His Boys—‘Over There.’” The Allies Special Aid knitting bag exhorted the efforts of the homefront knitters in military terms:

Do you belong to the wool brigade?

If not, then come along.

Mothers, wives and maidens

Make this Army strong.Gray Wool is our ammunition;

Some make it into balls

Pass them to the knitting squad;

They will soon use them all.For this is no time to be idle

And sit with folded hands

Pick up your knitting whenever you’re sitting.

A sock soon grows under your hand.Hark! I hear the bugle call.

Somebody wants another ball.

To assist these knitters, booklets of knitting patterns were issued. The Khaki Knitting Book, published by the Allies Special Aid organization in 1917, took the effort particularly seriously, with the following warning from the editor: “The money from the sale of the Khaki Knitting Book goes to the Allies and anyone lending the book to a friend who can afford to buy one, defrauds the Allies.”

People knitted not just at home but at work, at church, on public transport, in the theater, and while waiting for trains and sitting in restaurants. Female lifeguards in Southern California, covering for men who had gone to war, brought their knitting to the beach. A sitting grand jury in Seattle knitted socks. In 1915, the New York Philharmonic Society had to issue a plea for audience members to refrain from knitting, as it disrupted performances.

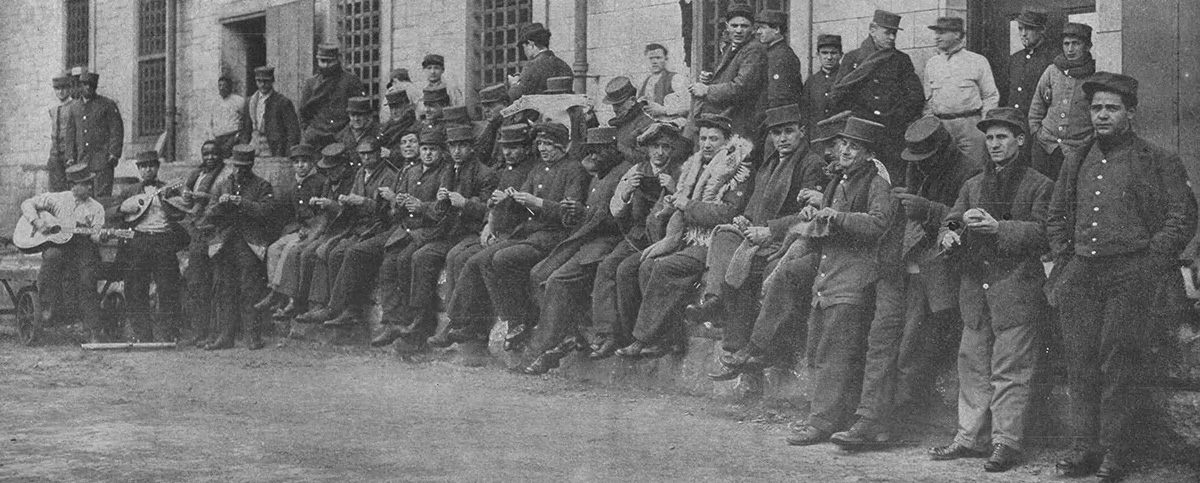

Men who had not gone to fight also contributed. There are accounts of Red Cross members teaching firemen to knit, train conductors knitting between stations, and inmates at Sing Sing knitting in the prison yard. Men were encouraged to knit at work during their lunch hours, and wounded soldiers knitted from their hospital beds.

The practice of knitting was so widespread that it became the subject of parody. In 1918, the New York Tribune ran a series of illustrations on the different types of knitters, including “Miss Tupper, who spends so much time watching to see if her neighbors are knitting … that she never gets very far along with her muffler.” Enthusiasm for knitting didn’t always translate to skill either. There is an account of the following verse from a soldier:

Life of a pair of socks

They are some fit!

I used one for a helmet

And the other for a mitt

Glad to hear

You’re doing your bit –

But who the ___

Said you could knit?!

The success of these homefront efforts is reflected in the staggering growth of the Red Cross at the time. Between 1914 and 1918, membership increased from 17,000 to more than 20 million. Its reach extended across the country, and included an estimated 35,000 Native American adults and children who also knitted for the war effort. In total, the Red Cross estimates that 370 million knit items were produced between 1917 and 1919. Today, knitting is still an active part of the Red Cross support for veterans.

Atlas Obscura has gathered a selection of photographs of the Wool Brigades of WWI.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook