The Anonymous Voices Behind Your Favorite TV Theme Songs

Sometimes you want to go where everybody knows your name… (Photo: Lara/flickr)

A version of this post originally appeared on the Tedium newsletter.

One of David Bowie’s last acts was releasing his album Blackstar, currently sitting at the top of the Billboard charts. Less well known is that Bowie helped promote the album by giving the title track to the album to the producers of The Last Panthers, a new TV show in the U.K.

It’s common enough, of course, for famous musicians to contribute TV themes: Think of HBO’s The Wire’s use of Tom Waits’ “Way Down in the Hole.” But most TV theme music doesn’t carry the pedigree of the Thin White Duke.

Shows like The Golden Girls, Cheers, Law and Order, and The Flintstones have songs that are significantly more famous than their creators. For the few who can make a career out of contributing original theme music, the rewards can be great. The creators of these themes hold the exact numbers close to their chest, likely because of the sheer complexity of the royalty system used, but if the show is one constantly in syndication, it could produce royalties in the millions.

Those who write original songs often become like sidemen, standing in the shadows of a classic TV show. There are the cartoon specialists, like Hoyt Curtin, who composed the music for many of Hanna-Barbera’s Saturday morning programs and the legal procedural pro Mike Post, who turned Law and Order work into a sonic kingdom. But no single icon of TV themedom stands out more than Jesse Frederick, the king of 1980s Friday night programming.

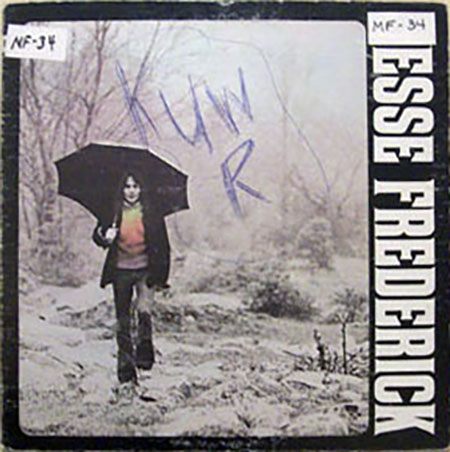

When Jesse Frederick began working as a musician, it was not with the goal of writing music for television. Frederick, a native of Salisbury, Maryland, belonged the singer-songwriter era of the 1960s and ‘70s. A troubadour with a voice and style comparable to Van Morrison, he was signed to Bearsville Records, the same label as Todd Rundgren, the Laura Nyro enthusiast who mastered Frederick’s self-titled record in 1971.

Jesse Frederick’s 1971 LP. In the 1980s, Frederick wrote and performed numerous TV theme songs. (Photo: Bearsville Records/WikiCommons)

Frederick’s work, unfortunately, was the worst kind of successful: it was critically acclaimed, but didn’t move units. Despite his later fame as a sitcom tunesmith, his album is so obscure that the usually-on-point music website Allmusic couldn’t be bothered to write a single sentence about him. Just 19 when the album, Frederick’s early failure wasn’t enough to stop his dream, however—he moved on from Bearsville and recorded a couple of other albums, none of which saw the light of day.

But sometimes, fate has a funny way of working out (which is sort of the lesson of all the theme songs he did). After scoring a handful of films, most famously the 1984 Garry Marshall flick The Flamingo Kid, Frederick followed Marshall to the producer’s usual medium—television. Starting a creative partnership with Marshall’s longtime music guy Bennett Salvay, the two musicians eventually followed producers Thomas L. Miller and Robert L. Boyett from Paramount to the just-formed Miller/Boyett Productions in 1985.

The first big Miller/Boyett project Frederick and Salvay took on was a little ditty for a show called Perfect Strangers. The song, “Nothing’s Going to Stop Me Now,” was instantly iconic—it had the quality of being both easy to remember and easy to parody. Frederick, however, did not actually sing the song that he wrote: that prize went to a man named David Pomeranz—who looks like what you would expect from a merger of Mark-Linn Baker and Bronson Pinchot.

Quickly enough, Frederick went from merely co-writing the songs to singing them. His voice—a raspy, bluesy tool—can be heard in the opening credits of Full House, Family Matters, and Step By Step. In total, Frederick did the theme songs for 12 different sitcoms in the 1980s and 1990s, the themes for which can be found on this page.

In the TV theme song world, there are those who write original music for the show, and those who just have their songs licensed. For the original writers especially, it can be very lucrative work. For example, TV impresario Merv Griffin wrote the Jeopardy! theme song as a lullaby for his son Tony in the late ’60s. Unlike most people who write lullabies, he copyrighted the tune—doing so 15 years before the show began to regularly use the tune. It made Griffin upwards of $80 million.

And Gary Portnoy, the guy who wrote the theme song to Cheers, was able to retire early, thanks to the show’s success and its longevity in syndication. It wasn’t clear at first, however, that it was going to last nearly that long.

“I think I got $150 for the Cheers theme. And I had a very powerful lawyer, and he just says, ‘Look, whatever it’s gonna be, it’s gonna be, but you’re not gonna make your money up front. So go for it,’” he told Marketplace last year.

Bob Denver, Gilligan on Gilligan’s Island, threatened to take his name off the show unless the full cast was credited in the theme song. (Photo: CBS Television/ Public Domain/WikiCommons)

This success, however, can cut both ways. Another (more famous) act that got lucky more recently, the Barenaked Ladies, has faced a bout of internal strife in recent months over The Big Bang Theory’s theme song, with former lead singer Steven Page claiming that he’s been cut out of the equation in favor of the guy singing on the theme song, Ed Robertson. Back in September, Page sued for 20 percent of the song’s proceeds.

Theme songs also have a way of resurfacing classic songs and driving interest into less-common parts of a musical act’s catalog—think Married With Children’s use of Frank Sinatra’s “Love and Marriage.” But at times, a theme song can turn a failure into a success.

Such is the case of “Thank You For Being a Friend,” the theme song to The Golden Girls. The tune, as originally released, was a one-hit wonder’s second attempt at a hit. Andrew Gold, the guy who wrote it, could only get it up to 25 on the charts, but that’s OK, because Estelle Getty made it famous. Cynthia Fee, the voice behind the TV show rendition, was a seasoned commercial jingle singer of the era, though she’s since branched out.

For the original theme song writers, the rewards go beyond just the financial. A popular show’s theme music becomes a cultural touchstone.

Most of the procedural shows in the ’80s and ’90s—and there were a lot of them—all had theme songs made by the same guy. Mike Post, who has created tunes for Law & Order, NYPD Blue, The Rockford Files, and Magnum P.I., among others.

He was so good at his job that show creators like Dick Wolf and Stephen J. Cannell asked for him by name. Post was also involved in Stephen Bochco’s Cop Rock.

Hanna-Barbera’s Hoyt Curtin’s influences were largely jazzy in nature, something that stands out in his most famous composition, the theme song for The Flintstones. The tune is based off of George and Ira Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm”—and as a result, the theme song itself has become a common jazz standard.

These days, the work of TV music production has in many ways followed in the steps of Jesse Frederick. Musicians with critical success who don’t have the sales to match that success have embraced the medium, which comes with a nice perk that most albums and tours don’t: a steady paycheck.

“It’s so crazy when you do work for people to pay you when it’s over. People in the music business say, ‘We’ll pay you 90 days after the next fiscal period, maybe if the accounting comes through.’ I was shocked when I first did some ads. I did the work and then they just paid for it,” explained Zach Rogue, the lead singer of Rogue Wave, in an interview with Pitchfork last year.

Rogue says that he found that the work, although mentally taxing, would allow him to be closer to his family. “I submitted to a TV show, but I was scared to get it, because I knew if I did that would be my life for a long time,” he noted.

He’s not alone, either; for example, ’90s female rock icon Liz Phair has made a second career out of the work, most notably soundtracking the 90210 reboot.

With the recent flood of classic TV reboots, audiences can be expected to hear their favorite theme songs all over again. However, the song that perhaps most put Frederick on the map more isn’t getting the anonymous-artist treatment.

“Everywhere You Look,” which you might better know as the Full House theme song, is about to get a remake, thanks to Netflix. The streaming service, which is planning to release Fuller House at the end of next month, will replace Frederick’s raspy, blues-inspired voice with the Jesse Frederick of the 21st century, Carly Rae Jepsen. Butch Walker, the Todd Rundgren of his generation, is manning the boards on the track. Truly, Frederick’s reign has proved unstoppable.

A version of this post originally appeared on Tedium, a twice-weekly newsletter that hunts for the end of the long tail.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook