The Wild Alaskan Island That Inspired a Lost Classic

A century later, “Quiet Adventure in Alaska” still sounds pretty good.

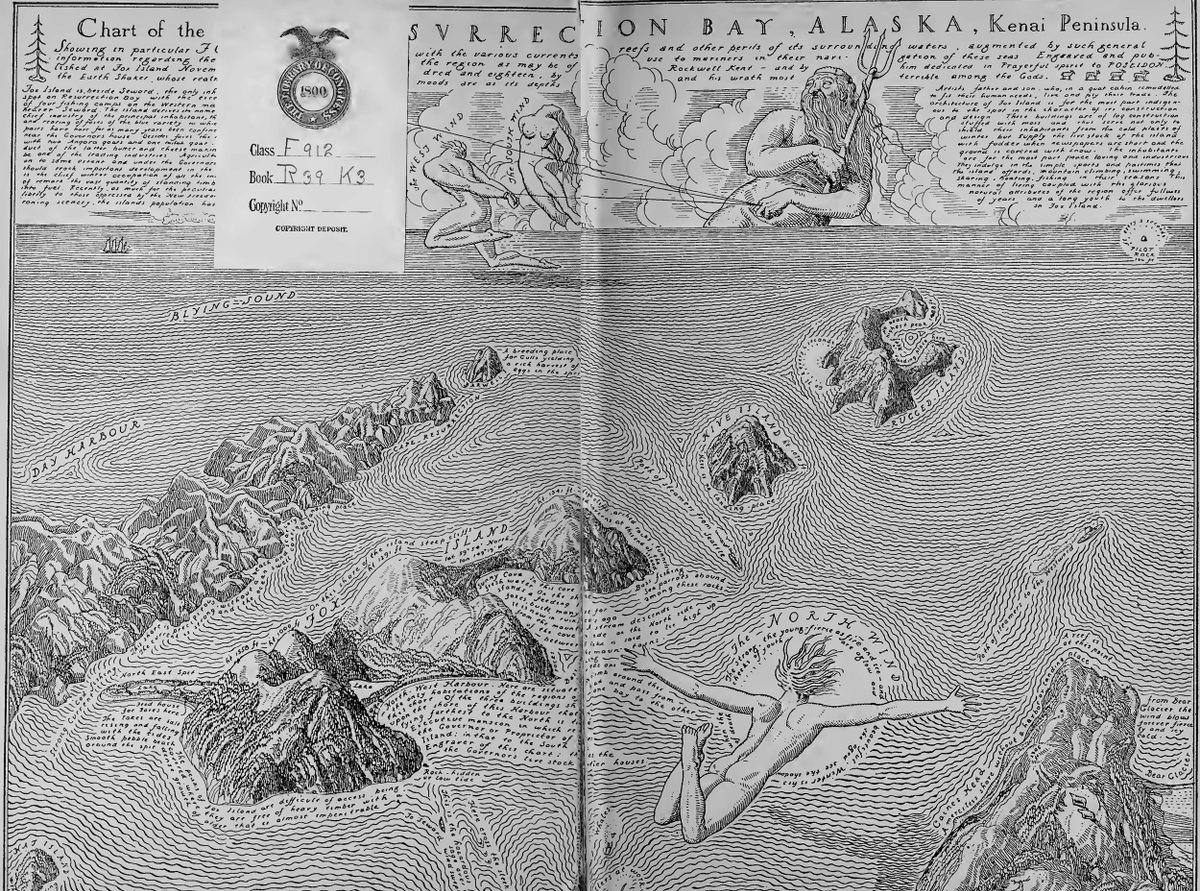

Rockwell Kent did not know where he would live in Alaska when he arrived in 1918. His intention, if it can be said that he had one, was to find a place apart from other people, and to paint. From Seward, a town full of men who had come north in search of gold, Kent and his young son—also called Rockwell—took a small boat into Resurrection Bay, where a chance meeting led them to an empty cabin on a small, wooded island. On August 28, under gray and drizzling skies, they loaded up their small boat and moved to Fox Island.

Kent was an artist from New York, a slight man with a long, sharp nose and a soft chin. Among his supplies was a heavy load of books—Nietzsche’s Thus Spake Zarathustra, both the Odyssey and the Iliad, a collection of poems by William Blake, and more. Alaska, he imagined, might provide fuel for his work for a time. He was a landscape painter, and this place had wild and unexploited natural sights and resources for a man like him.

Kent didn’t think of himself as writer, but in the months he spent on Fox Island, many nights were dedicated to letters home, describing the Alaskan days and nights in detail. That writing became a book, Wilderness: A Journal of Quiet Adventure in Alaska, and at least one British magazine thought it to be “easily the most remarkable book to come out of America since Leaves of Grass was published.”

One hundred years after Rockwell Kent, father and son, went to Fox Island, their own lonely, snowy paradise, discovering Kent’s book feels like uncovering a secret. Now little-known, Wilderness makes going off to the wilds of Alaska—as long as they’re not so remote, not as Into the Wild as the places Christopher McCandless sought—seem like an excellent idea. The book counts as a forgotten classic of nature writing, with striking illustrations by Kent, that paints a picture of people settled in lonely landscapes, a dream that seems impossible a century later.

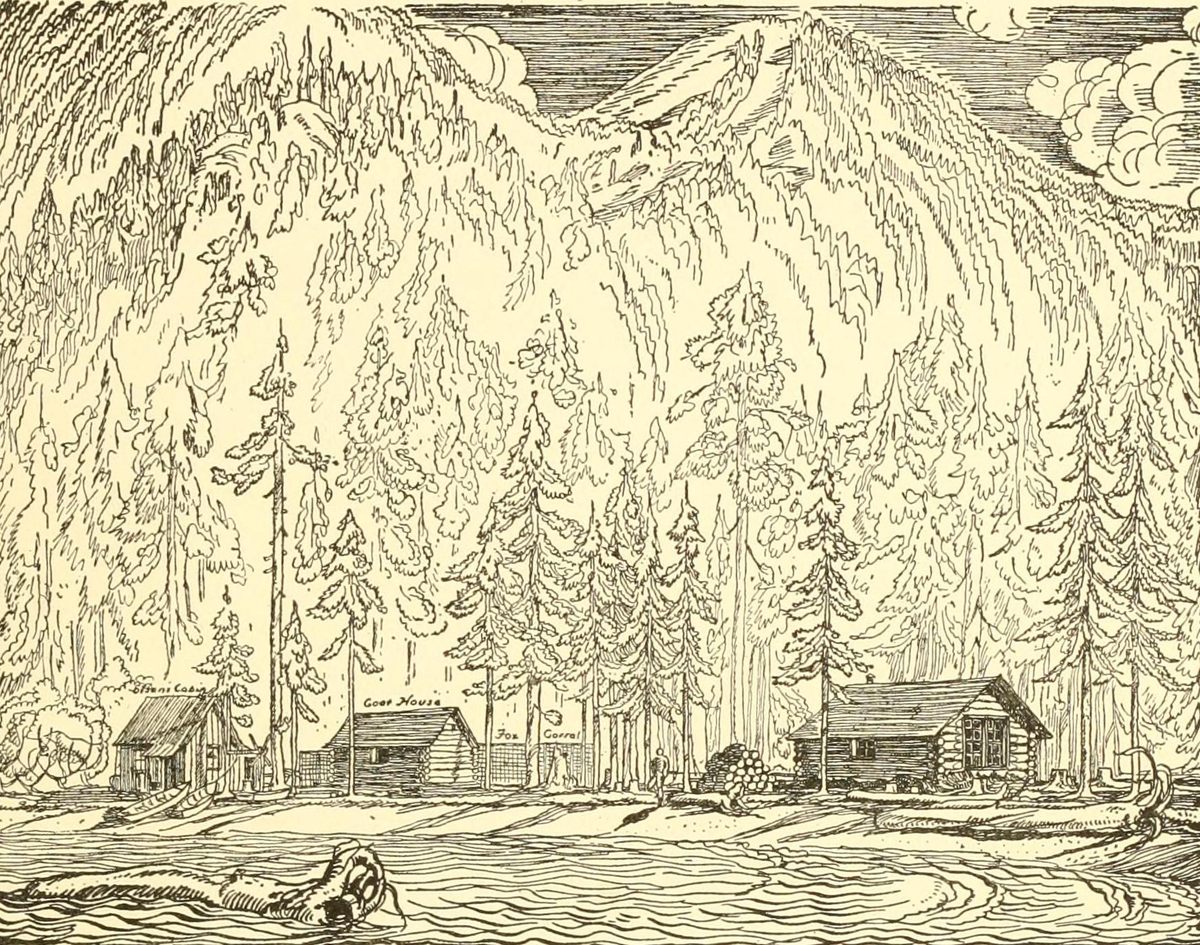

On Fox Island, life was simple. The two Kents settled into the homestead of the man they called Olson, who had built their cabin to shelter a herd of goats, which he still kept. The Kents stuffed the cracks of the cabin with moss and spent mornings cutting down trees, to feed their stove through winter. Many days were rainy, but Kent painted, as he intended, and sketched, and made wood-cuts, and he was happy with his work. And there were moments where they got that head-rush of outdoor glory. After climbing up one of the island’s mountains, “we stood in wonder looking down and out over a smooth green floor of sea and a fairyland of mountains, peaks and gorges,” he wrote. Or another time: “The night is beautiful beyond thought. All the bay is flooded with moonlight and in that pale glow the snowy mountains appear whiter than snow itself.”

Seward was less than a day’s boat ride away, but for the most part father and son were isolated. When the water was choppy, when the snow fell, when the wind picked up, which was most days, it was too dangerous to cross. They spent months alone with Olson, his goats, and the foxes he raised. The island felt to Kent like it was on the edge of human experience.

“A banana peeling on a mountain top tames the wilderness,” he wrote. “Much of the glory of this Alaska is in the knowledge I have that the next bay—which I may never choose to enter—is uninhabited, that beyond those mountains across the water is a vast region that no man has ever trodden, a terrible ice-bound wilderness.”

Kent is being naive here, though perhaps not willfully. Long before gold miners settled Seward, the area around Resurrection Bay had been peopled with native traders and hunters. He wrote that “so little do we feel ourselves related, here in this place, to any one time or to any civilization that at a thought we and our world become whom and what we please,” but this was because he bought into an idea of timeless, wild nature that doesn’t quite hold up 100 years later.

But at that moment, in that place, he had access to a land barely populated, with few rules to limit how he used it. Throughout the winter, the Kents razed a small forest to keep their fires burning, and young Rockwell kept trying to make pets of wild animals. They all died in his care. But the wilderness around them was robust enough to shrug off their presence.

Fox Island today is still covered in trees, and in the winter months it still seems apart from the rest of the world. But now it’s a managed wilderness, owned in part by the state and in part by a private tourism company that charges $1,280 per person for an overnight stay on the island. (Two nights minimum.) Alaska still has stretches unmarred by banana peelings, but the wilderness that’s easily reached from town has been spoken for, and Kent’s quiet adventure is the sort of experience that people will pay dearly for.

But in a way, the price that one pays to exist on Fox Island doesn’t really matter. Kent found timeless nature because he imagined it was there, and the people who travel to Fox Island on commercial cruises often find the same thing. If Seward now has a few thousand residents, instead a few hundred, it’s still little more than a fleeting concentration in a place where humanity is spread thin.

Kent first found his lure to the trees and water in the writings of Thoreau and Emerson, and this can be seen in his work, which has a transcendentalist bent, tinged with a 20th-century ambition and melancholy. For writers who encounter his work today, especially those who love Alaska, Wilderness has a similar allure. In a small way, the experience Kent found still exists. Anyone who has a small boat or strong arms can row out to Fox Island just as the Kents did and spend the night on the unimproved shore of the state parks, hoping the night stays beautiful and the moon shines over the bay.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook