One Artist’s Lifelong Quest to Create a Hidden Kingdom Called Rocaterrania

Its full history, which is being told for the first time in a new book, doubles as autobiography.

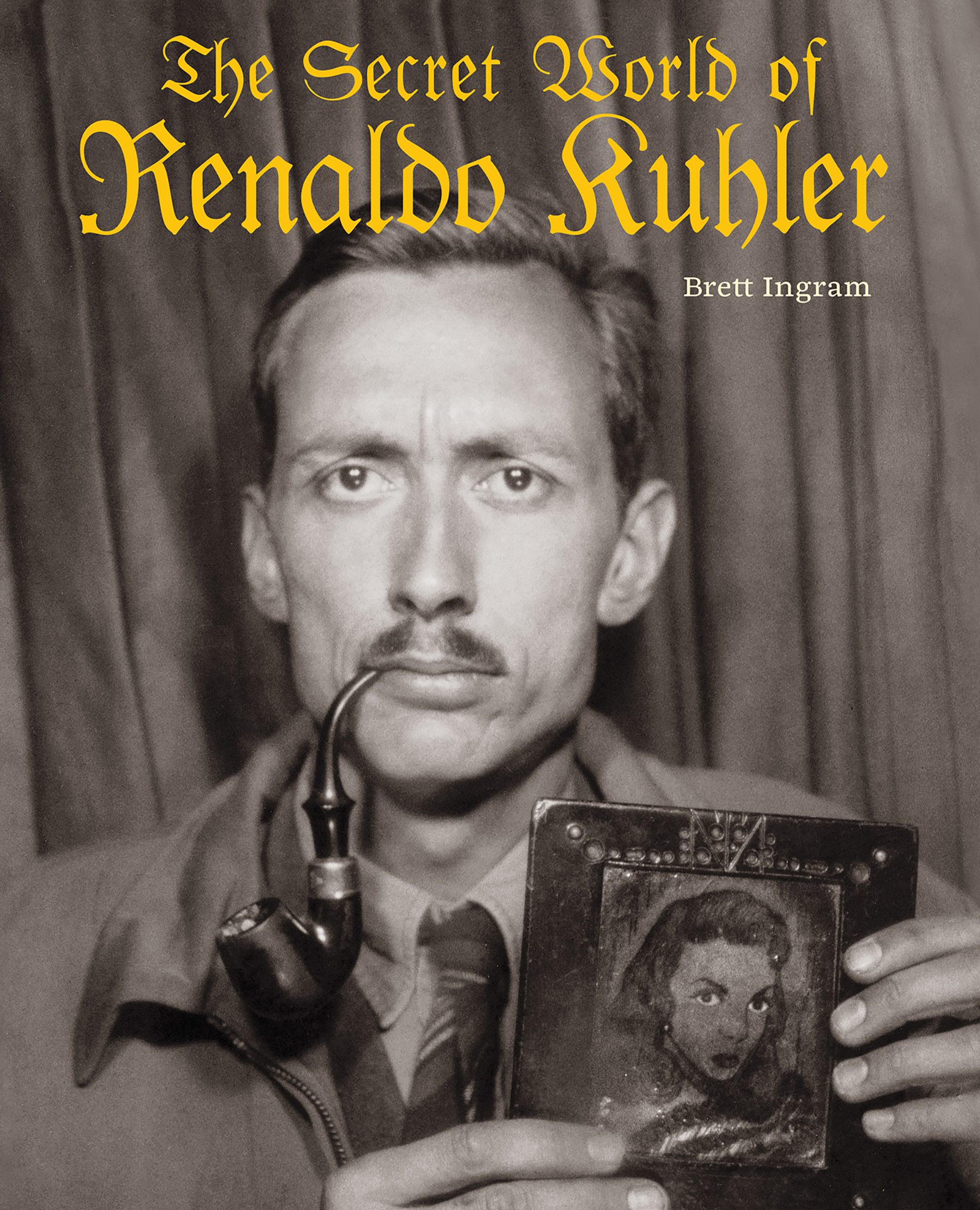

Renaldo Kuhler lived on his own terms. He loved bathtubs, he eschewed cars and computers, he played a plywood violin, and he sometimes wore a uniform of his own design, which showed off his long, strong legs. “Renaldo drank a lot, smoked a lot, talked a lot—to me, to himself, and to anyone within earshot,” writes Brett Ingram, author of The Secret World of Renaldo Kuhler. The one thing Kuhler did not talk about, not for decades, not to anyone, was Rocaterrania, the hidden kingdom he had created as a young man.

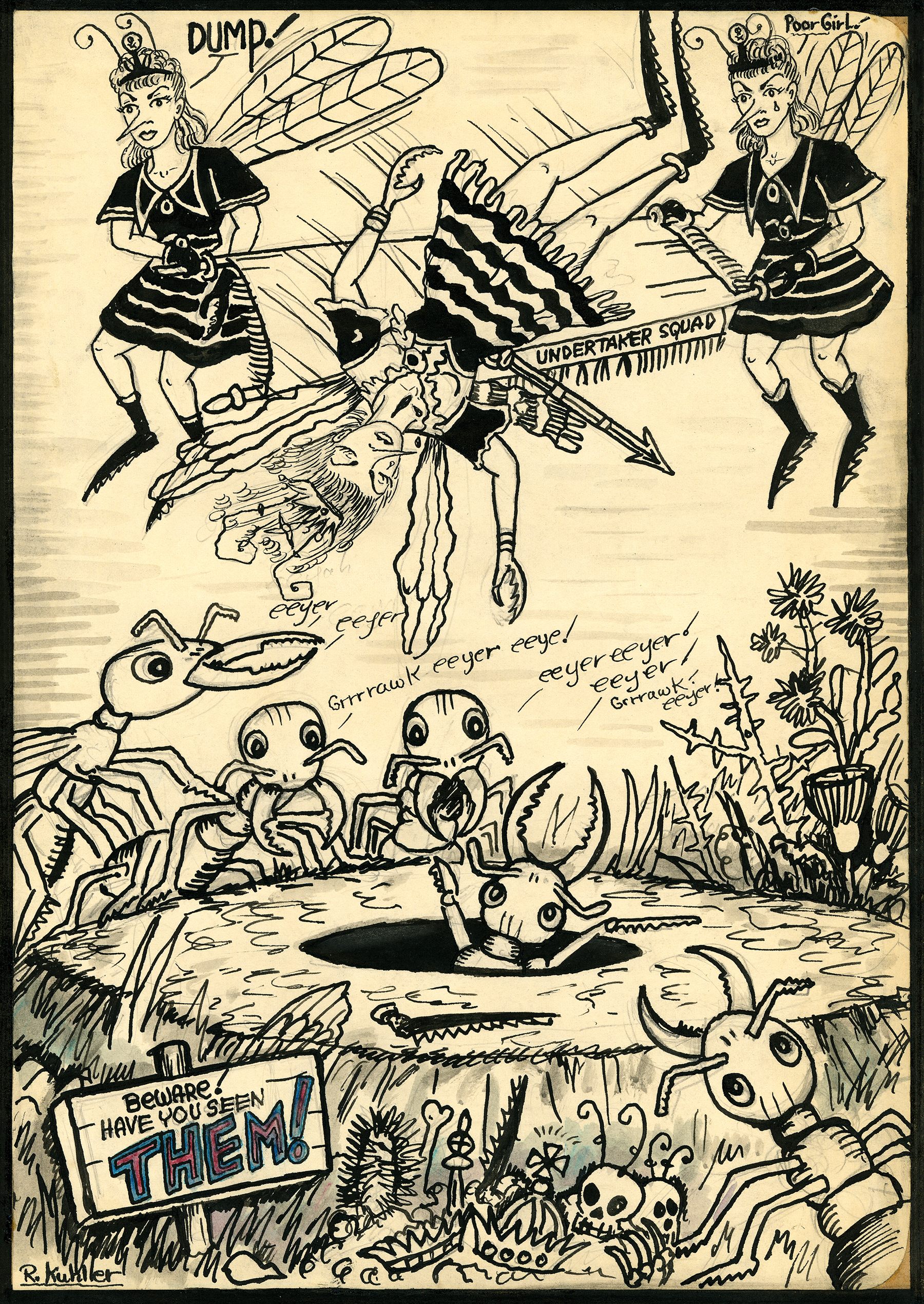

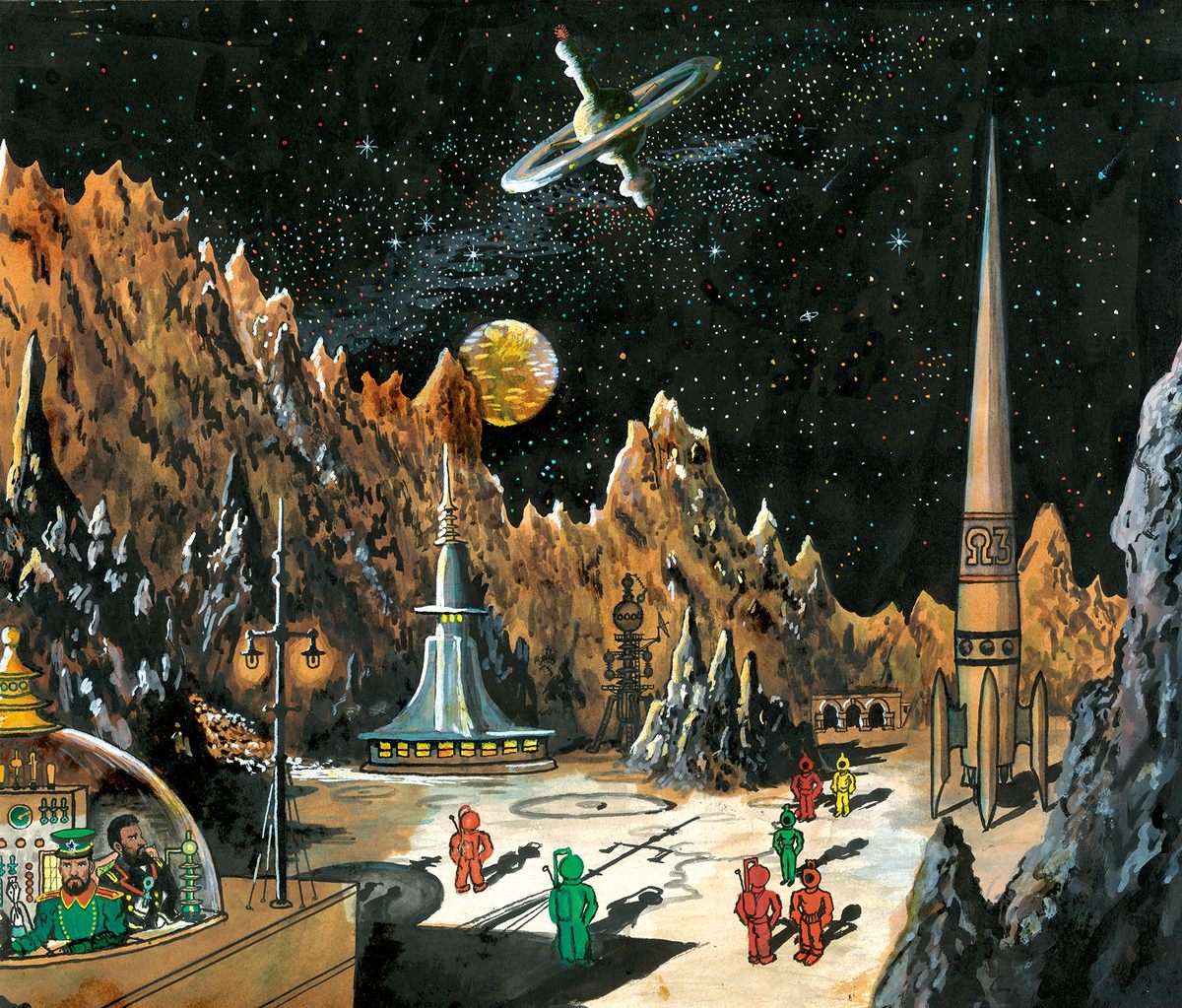

Over the course of his life, Kuhler made thousands of drawings—maps, portraits, landscapes, propaganda—illustrating the history of Rocaterrania. After Ingram started filming him for a documentary, Kuhler started to reveal the story of his secret land, a place of intrigues and revolutions, heroes and villains. The Secret World of Renaldo Kuhler, to be published this October, might be thought of as the first history of Rocaterrania. It collects Kuhler’s fascinating art and tells, for the first time in print, the full, epic story of the world he created.

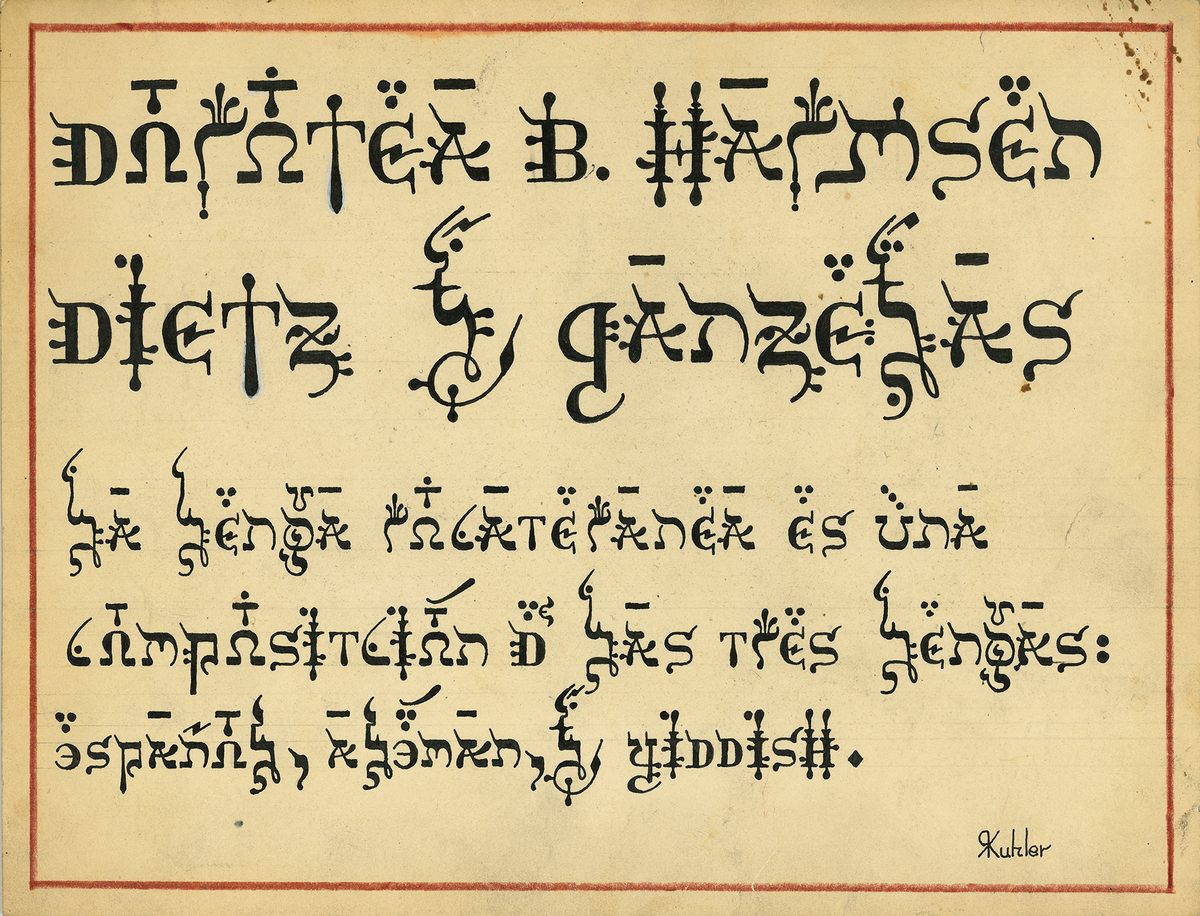

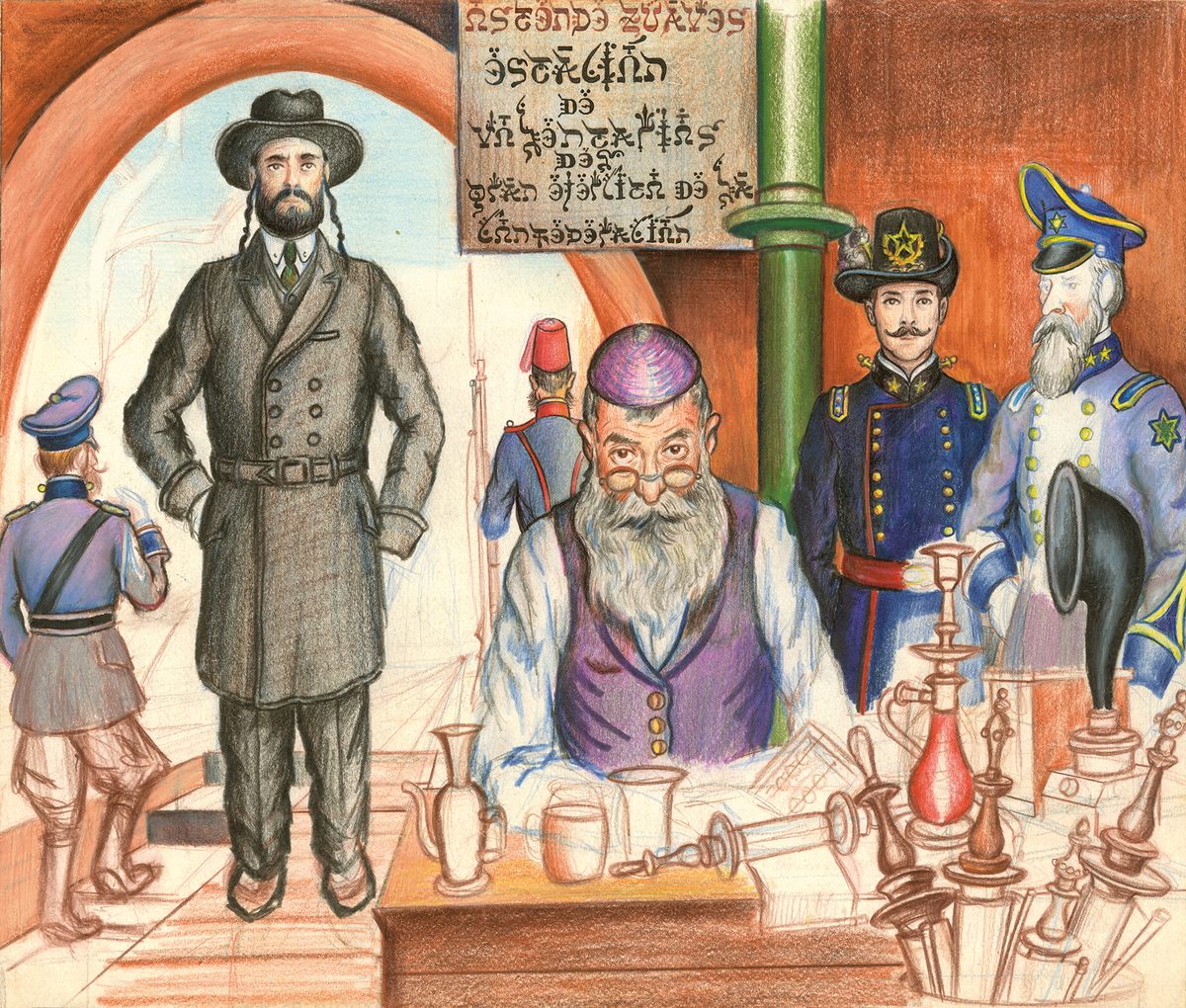

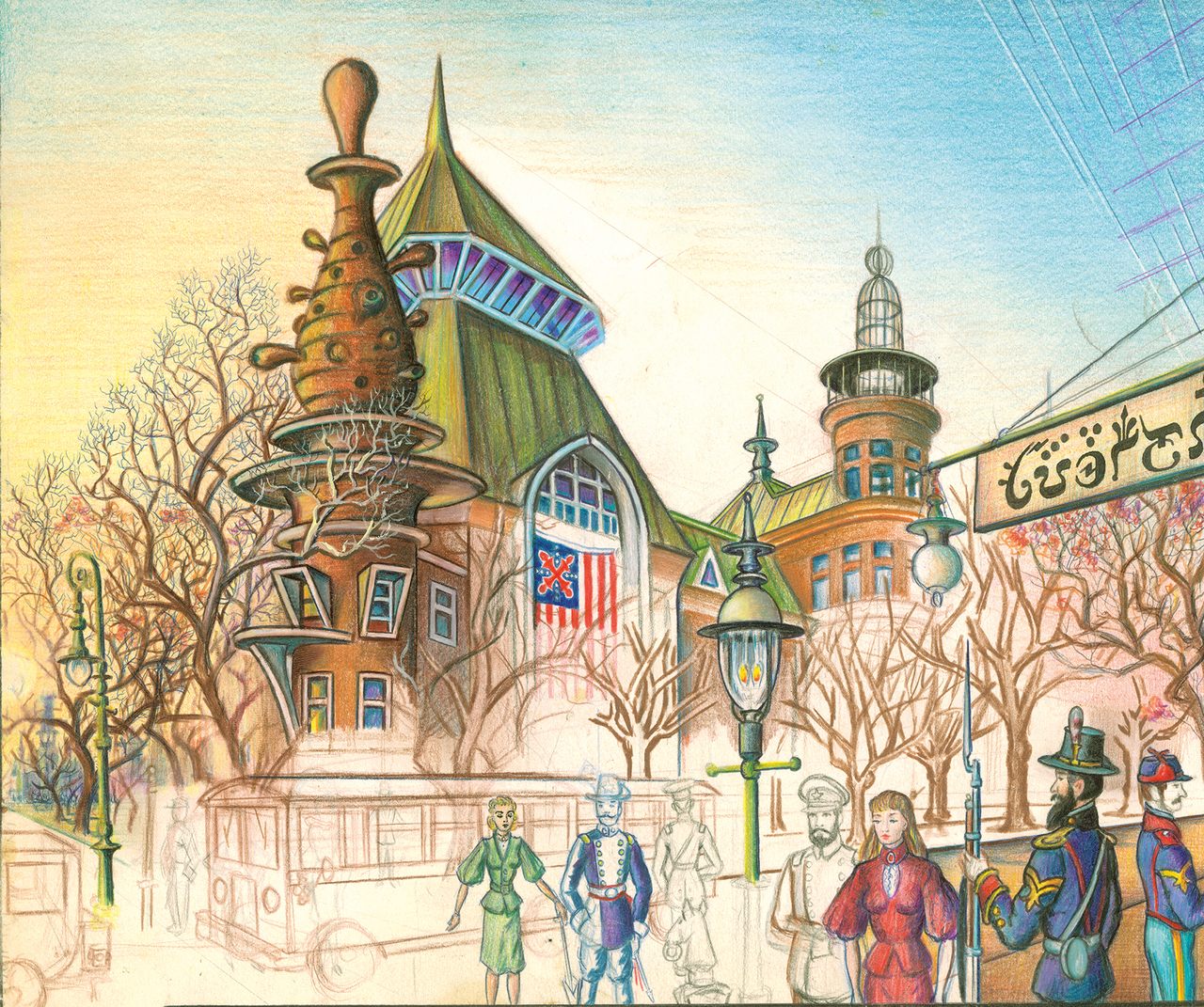

Rocaterrania was founded in 1931, when two wealthy American immigrants bought an expanse of land north of the Adirondacks, extending up to the Canadian border. Rocaterrania’s first leaders were monarchs, Phillippe and Catherine, who had little use for democracy. Their new country resembled old Europe, with streets that resembled Paris, an opera house in the capital, and a hard-working lower class of immigrant farmers and miners. As Rocaterrania’s population grew, the country developed its own culture, with its own language, based on Spanish, Yiddish, German, and English, and its own religion, Ojallaism, which drew from Judaism, Christianity, and Islam.

The people of Rocaterrania, though, were unhappy with monarchical rule, and the country’s history was marked with revolts. The monarchy was forced to recognize an autonomous region, New Serbia, and was eventually overthrown by socialist rebels, who held democratic elections.

Under this new political order, innovation and culture flourished in Rocaterrania. The environmentally minded government created systems to recycle waste into fertilizer and created a Rocaterranian Conservation Corps that helped build up the country’s infrastructure. Rocaterranians started their own version of the Olympics, and a film industry blossomed.

The history concludes: “It took many hard years of struggle, dark days and night, for Rocaterrania to become the nice place it is today but, no question about it, they made it.”

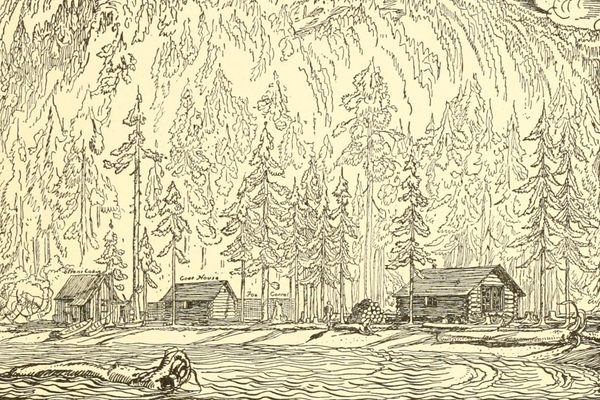

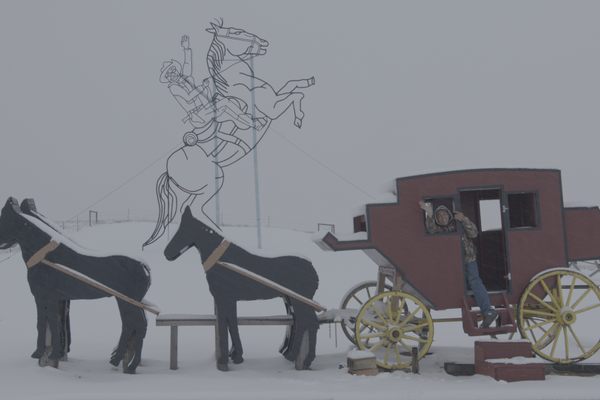

Kuhler dreamed up Rocaterrania as a young man, discontented with the rule of his parents. He was born Ronald L. Kuhler in 1931, to European immigrants in New Jersey. He spent his childhood in New York’s Rockland County before his father moved the family to a cattle ranch in Colorado. Isolated, uninterested in becoming a cowboy, intrigued by art, music, language, and history, Kuhler escaped into an imaginary world.

Even after leaving home, he continued to spool out the story of Rocaterreania while working as a historian in Washington State and a scientific illustrator in Raleigh, North Carolina, where Ingram met him. Rocaterrenia wasn’t just a made-up world; it became a metaphorical history of his life. “Rocaterrania is not a utopia,” he told Ingram. “It is not a fairyland or dreamland. What it is, it indirectly tells the story of my life and my struggle to become what I am today. I am Rocaterrania, and my troubles within me and everything else, the events of my life.”

Read the history with that understanding and the undercurrents of Kuhler’s personal story start to emerge. When Phillippe, the first emperor, is described as a “benevolent, if somewhat inscrutable, monarch” and Catherine, the first empress, as “rather domineering,” Kuhler’s feelings about his parents come into focus. When an early rebellion gives one part of the country “substantial autonomy to govern their own affairs,” it maps onto the moment when Kuhler’s parents let him live in his own cabin on the ranch, granting him a partial freedom.

Kuhler’s tastes map onto Rocaterrania, too. Ingram writes that Kuhler donated generously to environmental causes; Rocaterranians are avid environmentalists. He played the violin; Rocaterranians revere the opera. Like Kuhler, the early monarchs loved trains, and they built a lasting system of urban transit and long-distance rail, so the country never developed a car culture. It’s even possible to read certain characters as aspects of Kuhler himself, too, and eventually a Ronald L. Kuhler and his twin sister, Renalda Kuhler, immigrate to Rocaterrania. Ronald quickly falls in love with one of the daughters of a well-regarded Rocaterranian family, and Renalda purses a career as an enterprising journalist.

As Rocaterrania matures as a country, its people find greater creativity and freedom. By the time Ingram met Kuhler, in the 1990s, he had found some of that same freedom. Kuhler “was unabashedly, unapologetically, incorrigibly himself as a moral imperative,” Ingram writes. The project of creating Rocaterrania and recording its history helped him realize a more fully expressive life for himself. Kuhler passed away in 2013, five years after Ingram completed his documentary, Rocaterrania. “The ability to fantasize is the ability to survive,” he told the filmmaker. Rocaterrania made that possible for Renaldo Kuhler.

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook