Lady Jane Franklin, the Woman Who Fueled 19th-Century Polar Exploration

Determined and dedicated to the sciences, she dispatched many a vessel to the Arctic.

On the Scottish island of Unst, boatmen once told stories of an English widow who journeyed out to a tiny, rocky islet on the northernmost point of the British Isles. Lady Jane Franklin would gaze north across the sea and “send [her] love on wings of prayer” to her long-lost husband Sir John Franklin, the famed Arctic explorer and naval officer who set sail in 1845 in search of the Northwest Passage.

“Those who were there said she stood for some minutes on the somber rock, quite silent, tears falling slowly, and her hands stretched out towards the north,” Jessie Saxby, an author of the region, wrote.

While some stories portray Lady Franklin as a weeping widow and devoted wife, she was much more than that. Lady Franklin was an unrelenting force who propelled the search for her husband, along the way establishing herself as an important figure in polar exploration during the late 19th century.

In 1845, John Franklin led two ships, the HMS Erebus and the HMS Terror, carrying 129 crewmembers, into the uncharted territory of the Arctic. They never returned. The lost expedition remains one of the greatest ongoing mysteries in the history of polar exploration. This is in part due to Franklin’s second wife, Lady Jane Franklin, a tenacious, well-traveled woman who fueled a series of polar missions to locate the expedition and find out the fate of her husband. As one newspaper of the era put it, “What the nation would not do, a woman did.”

“The first few [search parties] were created by the British Navy, but when they were unsuccessful, she pushed for American involvement and she actually bought her own ship later on,” says Douglas Kondziolka, a neurosurgeon and professor at New York University Langone Medical Center, who recently presented his collection of Arctic and Antarctic exploration books and documents at the New York Academy of Medicine.

While Franklin may have physically explored the vast frozen land, Lady Franklin had funded voyages that significantly contributed to charting the Arctic.

“Jane Franklin was the 19th century’s most famous widow, next only in public stature to Queen Victoria,” wrote Amanda Johnson in the Journal of the Association for the Study of Australian Literature.

Lady Franklin was born Jane Griffin in London on December 4, 1791. Her mother died when she was young and her father was a wealthy silk manufacturer. Growing up, she received the limited education available at the time but her father encouraged her to pursue her curiosities. She was self-taught, a prolific diarist and “fiercely energetic,” Johnson wrote. In 1828, at the age of 37, she married John Franklin, who by that time had already journeyed to the Arctic twice. A year later he was knighted for his 1825 expedition, which charted thousands of miles.

Atypical of women at the time, Lady Franklin was an explorer and adventurer herself. Some scholars have called her one of the most traveled women of the Victorian era.

“Few women of her class and era had the opportunity to stamp their presence on so many parts of the world,” wrote Penny Russell in Victorian Studies.

At a young age, Lady Franklin toured countries throughout western Europe with her father and two sisters. She later explored areas of Northern America, countries in Asia, and colonies of South Australia and New Zealand. She once descended down a crater in Hawaii, became the first woman to climb Mount Wellington, and even has a mountain named after her in Victoria, Australia. During her adventures, Lady Franklin faced storms and near-starvation at sea, and experienced travel by many modes of transport, from naval ships, camels, to palanquins and sedan chairs, wrote Russell. When Franklin was stationed in the Mediterranean in 1830, Lady Franklin accompanied him and traveled around Greece and northern Africa with growing independence, said Russell, and had even ventured with only two or three servants.

In 1836, Franklin was appointed governor of the Australian penal colony Van Diemen’s Land—modern-day Tasmania. Because of her husband’s political position, Lady Franklin was able to be involved in the growth and development of the colony. She was extremely passionate about science and education.

“Settler locals soon learned to loathe her for cheerfully replacing balls with public lectures on botany, science and ethnography,” wrote Johnson.

She built a sandstone Greek temple to house a natural history museum, bought 130 acres of land for a horticulture garden, and published a scientific journal. Her “hobbies of hobbies,” she once said, was the foundation of a state college. Lady Franklin was also involved with reforming conditions of female prisons, and—controversially—took two Aboriginal children into temporary care.

“Colonists were appalled by her obvious interest in their affairs, and almost from the moment of her arrival she was mercilessly satirized in the colonial press,” wrote Russell.

The Franklins returned to England when John Franklin was recruited for another expedition to find the Northwest Passage, the sea route through the Canadian Arctic Archipelago that would allow a much shorter voyage from Europe to Asia. While the warming climate has opened the Northwest Passage today, explorers in the 19th century didn’t know that the thick, year-round sea ice made the path impossible to sail through.

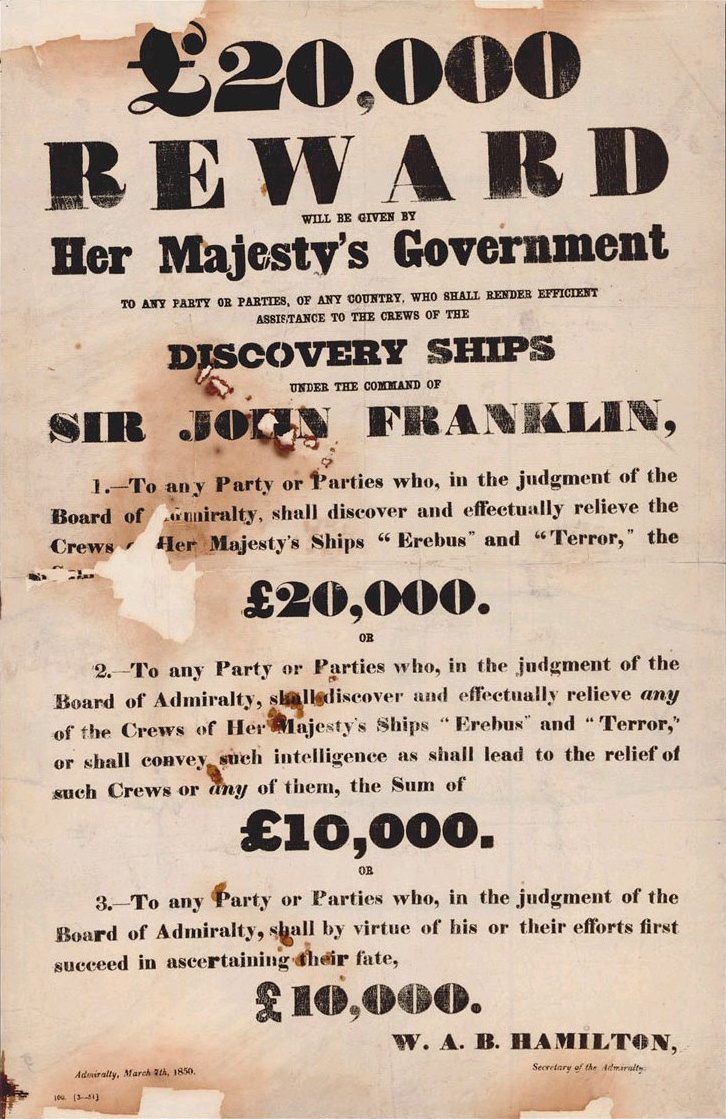

Despite being a seasoned Arctic explorer, Franklin and his two ships became trapped in the frozen, desolate land. After three years and no sign of Franklin, the British Navy began sending out search parties and even posted a reward for the crew who found evidence.

“Books were published about the Franklin expedition and the public became very interested in this search for the next 25 to 30 years,” Kondziolka says. “That stimulated a lot of additional people to get involved.”

The most avid and relentless instigator behind the search was Lady Franklin. She wrote to newspapers, rallied helpers and other explorers, pushed government officials, and roused public sympathy for the missing men, wrote Russell.

Previous explorers and crew had survived for four to six years—if they met Inuit, people thought maybe they could stay alive for 10 or 11 years, says Kondziolka. But as the years passed by and there were still no telltale signs of what had happened to Franklin, the British government began to wane in its effort despite Lady Franklin’s petitions and letters to the prime minister and even the U.S. president. Instead of giving up, she took matters into her own hands and funded seven missions to retrieve evidence of her husband’s location, recruiting the help of American explorers.

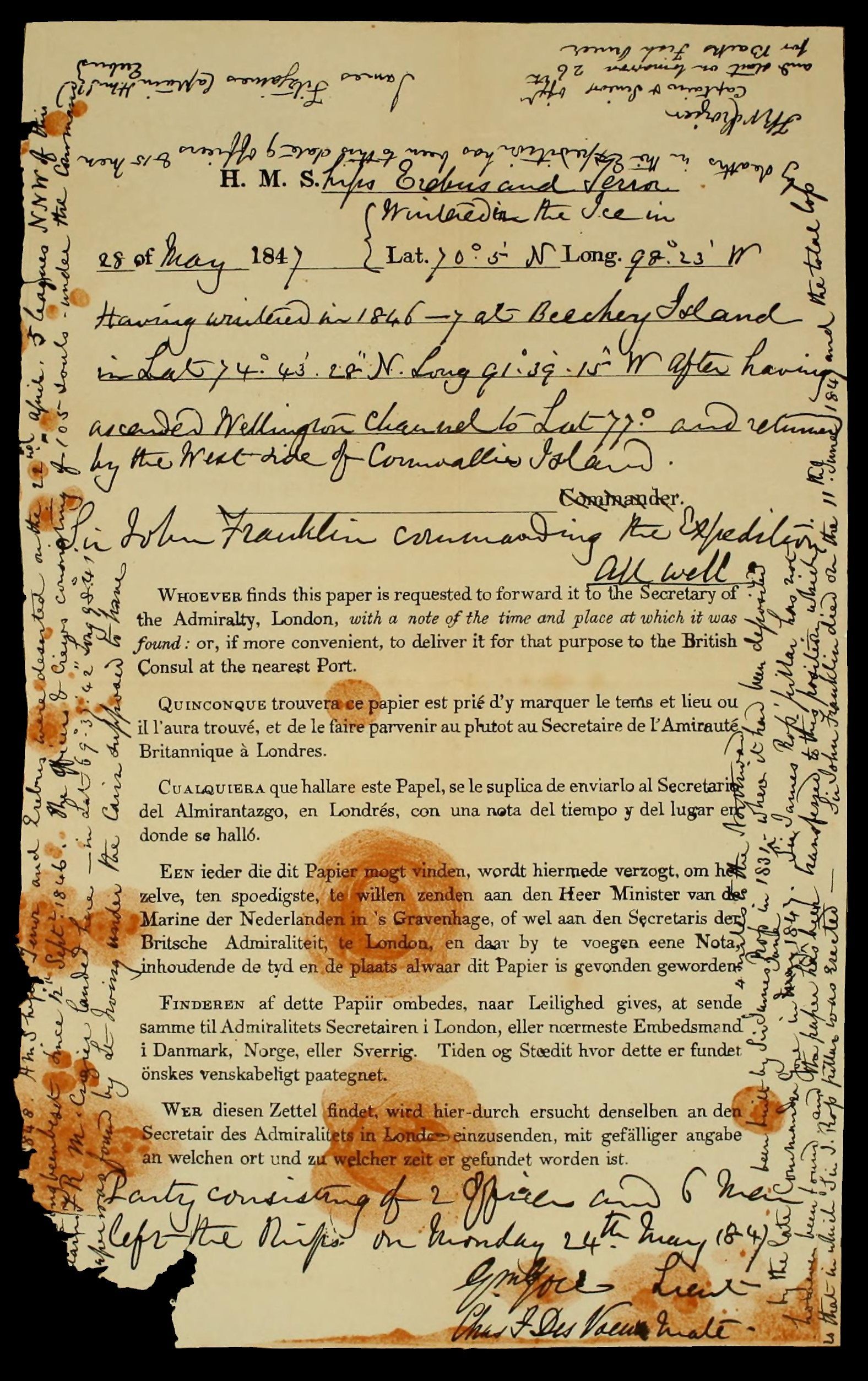

“One of the things later on, from her perspective, was if her husband found the Northwest Passage before he died and therefore should be given the glory of finding it,” says Kondziolka. The various explorers she commissioned hunted for relics, until in 1859 Francis Leopold McClintock returned on Lady Franklin’s ship the Fox with some dismal news. In a tin under a pile of rocks, preserved by permafrost, was a message that stated (in about six different languages) that Franklin had died within a year of the expedition.

Wanting to retrieve Franklin’s missing written records, Lady Franklin continued to send vessels to the Arctic until her death. She commissioned one final search that set sail on June 1875 only weeks before she died on July 18, 1875.

More than 150 years later, the spirit of Lady Franklin’s search for her lost husband still lives on. In September 2016, the HMS Terror was finally located in its watery grave near King William Island in the Canadian Arctic.

Explorers aboard Lady Franklin’s vessels, dispatched to find evidence of her husband’s fate, also made many of their own discoveries and documentations. They recorded flora and fauna of the Canadian Arctic, surveyed the west coast of Greenland, and Sir Robert McClure found the Northwest Passage on a Franklin search expedition supported by the British Navy in 1850. Her involvement inspired explorers to reach the most northern tips of the earth.

“She was very responsible for some of the key players, such as getting the Americans involved in polar exploration,” says Kondziolka. “Asking them for help started off a 30-year process of one American expedition after another which eventually led to the accomplishment of going to the North Pole in 1908. That really started with her.”

Follow us on Twitter to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Like us on Facebook to get the latest on the world's hidden wonders.

Follow us on Twitter Like us on Facebook